Why Hawthorne was Melancholy: The “Lost Clew” Explained

/“Ah! who shall lift that wand of magic power,

And the lost clew regain?

The unfinished window in Aladdin’s tower

Unfinished must remain.

”

““I should roughly define the first spirit in Puritanism thus. It was a refusal to contemplate God or goodness with anything lighter or milder than the most fierce concentration of the intellect. A Puritan meant originally a man whose mind had no holidays. To use his own favourite phrase, he would let no living thing come between him and his God; an attitude which involved eternal torture for him and a cruel contempt for all the living things. It was better to worship in a barn than in a cathedral for the specific and specified reason that the cathedral was beautiful. Physical beauty was a false and sensual symbol coming in between the intellect and the object of its intellectual worship. The human brain ought to be at every instant a consuming fire which burns through all conventional images until they were as transparent as glass”.”

On a sunny day in January at the end of a visit with an old friend in Kentucky, Dennis Musk approached our car as we were about to head off to another talk in Cincinnati and handed us what looked like a holy card of the sort I remembered from my Catholic youth. On one side, there was a picture of Rose Hawthorne, in full Dominican habit as Mother Mary Alphonsa, and on the back, there was a prayer:

Lord God in your special love for the sick, the poor, and the lonely, you raised up Rose Hawthorne (Mother Mary Alphonsa) to be the servant of those afflicted with incurable cancer with no one to care for them. In serving the outcast and the abandoned, she strove to see in them the face of your son. In her eyes, those in need were always “Christ’s Poor.”

Grant that her example of selfless charity and her courage in the face of great obstacles will inspire us to be generous in our service of neighbor. We humbly ask that you glorify your servant, Rose Hawthorne, on earth according to the designs of your Holy Will. Through her intercession, grant that Angela Hapner Musk be cured of her brain cancer, Through Christ Our Lord, Amen.

The name Rose Hawthorne brought together a number of threads that made up the tapestry of my life. In the immediate present, we knew a number of people who were suffering from cancer, and so we started praying for them, asking Rose Hawthorne to intercede. The prayer seemed to have an immediate effect. Ken Kanczuzewski bounced back from his surgery for lung cancer and seemed on his way to full recovery. Tom Brammer, who had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer in the spring and should have been dead, seemed to revive when I told him about the prayer.

Tom moved into my life around 20 years ago when he left Florida and bought a house next to the Buttigieg family, two houses west of where I have lived for the past 40 some years. Pete’s mother used to brag to Tom about Pete hanging out at Boys’ Town and other gay bars in Chicago long before Pete announced publicly that he was a homosexual and even longer before he became the most incompetent Secretary of Transportation in American history. Tom moved into the house with his then girlfriend and they had four children together before she moved out. The house remained a mess because he didn’t have time to fix it because the work he did in flooring involved moving back and forth from Florida, where he acquired the lifestyle that probably contributed to him contracting cancer and alienated him from the Catholic faith he had been raised in.

The major trauma in Tom’s life came when his father Harold committed suicide. Tom was the oldest of the 12 siblings left in Florida after his father had gone there to restart his business career for the third time. In addition to working for the CIA, Harold Brammer had become the wealthy head of a mortgage brokerage firm in McLean, Virginia, but lost that company when he got swindled out of his business by his partner. He then moved to South Bend, where he failed to replicate what he had started in Washington, and then moved to Florida, where he failed a second time and then killed himself. Tom was still a teenager when he got the call from the police to come to the morgue to identify the body.

The sudden death of Tom’s father left a crater in the Brammer family. Those who were too young to understand what had happened or already living on their own were spared, but the children in the middle lost whatever direction the family had from its depressed father and drifted into culturally approved forms of antisocial behavior that, unsurprisingly, were not healthy either. Tom, like his father, had come back to South Bend for a second chance with no sense of the tenacious hold the bad habits he had acquired in Florida had over him.

The Hawthornian Angle

There was a Hawthornian angle to this story. Raised in Puritan New England, Nathaniel Hawthorne understood that the Calvinist break with the sacraments of the Catholic Church had created a culture in the new world where evil was the nature of man, and man was predestined by his sins because he could no longer go to confession. Tom never gave up believing in the God whose Only Begotten Son created the Catholic Church, but his behavior alienated him from the Church’s sacraments in a way that was detrimental to his health, both spiritual and physical.

In the remoter past, the name Rose Hawthorne conjured up an unwritten chapter in The Angel and the Machine, the book that grew out of the doctoral dissertation I wrote on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s rational psychology during the winter and spring of 1978. Hawthorne was an acute observer and a man of exquisite sensibility whose life was dedicated to the pursuit of beauty in what he observed and what he created. I had to wait almost 50 years to finish the book I started in the 1970s because I didn’t know then that the artist could often portray what the philosopher cannot explain and could not know how that category of thought explicated Hawthorne’s life until I had written The Dangers of Beauty.

The mystery at the end of every biography of the famous author of The Scarlet Letter found expression in the unanswered question asking, “Why Hawthorne was melancholy?” Marion Montgomery wrote a long book with that title which did little to clarify the mystery. The profession wasn’t helpful either. By the time I got around to writing my dissertation on Hawthorne, the first shots had been fired in a culture war which would eventuate in the death of Literary Criticism (and the English major) in what began as a Protestant-Jewish battle over the New Criticism, the regnant critical theory when I began my career as an undergraduate English major in the fall of 1966.

During the course work for my Ph.D., which began in 1976 after I returned from years of teaching English at a German Gymnasium, I took a course taught by Stanley Fish, one of the Jewish protagonists in that war. New Criticism was Protestant, based on a secularized application of the principle of sola scriptura, which insisted that every man had the right to interpret a poem as he saw fit. New Criticism fit in with the post-WWII return to orthodoxy among the Protestants, but it was also democratic in a way that its rival was not. Fish and Deconstructors like Jacques Derrida, who was then teaching at Yale, proposed a Talmudic alternative to the New Criticism by arguing that only the rabbis, i.e., professors like Fish and Derrida, had the right to comment on the poem, which was the secular replacement of the Torah.

The late 1970s corresponded to the twilight of the sexual revolution, as widespread lust lurched toward violence and got chronicled in horror films like Halloween, which premiered in 1978, and Alien, the sequel to pornography like Deep Throat, which premiered one year later. The collapse of sexual morality at the university was leading to unexpected consequences for Literary Criticism. During a discussion of The Scarlet Letter in a class on Hawthorne taught by Jane Tompkins at Temple University, a student perplexed by her cavalier treatment of the sin around which the entire story revolved asked, “Isn’t adultery wrong?” Jane was clearly embarrassed by the question because she had already dumped one husband and was on her way to becoming Literary Criticism’s most famous shiksa, which happened when she ran off with Stanley Fish, whom she met in the same class I was taking with him.[i]

Jane would go on to document her adultery with Stanley Fish in a memoir which came out when they were the lit crit power couple of the 1990s and used that position to run lit crit into the ground with the help of a professoriate which shared their views on sexual morality. Nathan Heller wrote the obituary for the lit crit crowd in the February 27, 2023 issue of the New Yorker in his article “The End of the English Major” without coming to any conclusion about the cause of its death which I articulated in “Stanley and Jane’s Excellent Adventure” when I wrote:

Jane was faced with two equally repugnant alternatives. First, there is the literary alternative. If she says, “no, adultery isn’t wrong,” then she immediately trivializes The Scarlet Letter and virtually every other major piece of literature since Homer. If adultery is not a big deal, then why are Hester and Dimmesdale so upset about it? If, on the other hand, Jane says, “yes, adultery is wrong,” then she condemns the mores of virtually all her colleagues and reveals herself as terminally unhip.[ii]

The result of this literary coup d’etat was silence on the issue of why Hawthorne was melancholy. Both the New Criticism of the dying WASP critical elite, symbolized best by Northrop Frye, and the Jewish revolutionaries I have already mentioned had nothing to say because both were formalistic in ways that yielded answers automatically with no regard to the personal and historical circumstances of the author of the text. Almost 50 years ago I wrote The Angel and the Machine about the fundamental paradox at the heart of Hawthorne’s rational psychology, which saw man as an unstable compound made up of an angel, which corresponded to his soul, and a machine, which corresponded to his body. Hawthorne was a respected citizen of Concord, Massachusetts, whose inhabitants were the church-going, socially conservative heirs of the revolutionary movement known as Puritanism. The name of that paradox was Unitarianism, which Perry Miller described as “‘liberal’ in theology” but “conservative” in its “social thinking and its metaphysics.”[iii]

In “From Edwards to Emerson,” Perry Miller claimed that Ralph Waldo Emerson derived Transcendentalism from native Calvinist sources. Like John Milton who made Satan the hero of Paradise Lost, Emerson espoused a satanic form of rebellion in “Self-Reliance” which endeared him to both New England Unitarians, who were determined to preserve social propriety in spite of their revolutionary ideas, and Friedrich Nietzsche, who deliberately infected himself with syphilis after hearing Tristan und Isolde and had nothing but contempt for “flatheads” like George Eliot, who were determined to preserve Victorian sexual morality while espousing philosophical nihilism. Both Hawthorne and Emerson shared an allegiance to the “dual heritage”[iv] of New England, which:

commenced with a clear understanding that both mysticism and pantheism were heretical, and also with a frank admission that such ideas were dangerous to society, that men who imbibed noxious errors from an inner voice or from the presence of God in the natural landscape would reel and stagger through the streets of Boston and disturb the civil peace.[v]

Miller continues by saying that “the emergence of Unitarianism out of Calvinism was a very gradual, almost an imperceptible, process.”[vi] Gradual or not, the main thing that changed in New England during the period which stretched from “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” to “Self-Reliance” was the Calvinist understanding of Original Sin. Authors Otto and Katharine Bird claimed that “The denial of original sin and the inheritance of it was a hard blow against orthodox Puritan belief. But the killing blow came with the denial of the divinity of Jesus Christ and the turn to Unitarianism.”[vii]

Hawthorne kept the New England Puritan legacy alive in his tales and novels. His farewell to Calvinism was as tentative as his acceptance of the regnant Unitarian orthodoxy of his day, symbolized best by Emerson. Judging from the standards of the late 20th century, Montgomery concludes that: “Hawthorne’s Roger Chillingworth stands forth to our experience as a more convincing figure of man than Emerson’s ‘Man Thinking.’ The fictional character is firmly anchored in the realities of the human heart, while Emerson’s dream image has about it the vagueness of wishful thinking.”[viii]

Hawthorne hated Calvinism, but he was reluctant to abandon the idea of Original Sin as completely as Emerson had done. Bereft of sound theological principles because of his cultural background, Hawthorne was incapable of correcting either Edwards’s exaggeration of the effects of Original Sin or Emerson’s dismissal of it, but, forced to choose sides, Hawthorne chose Puritanism over Transcendentalism as the more realistic alternative. Rather than refute Calvinism theologically, Hawthorne chose to portray the psychological consequences which flowed from its premises. Nothing makes this more evident than the great speech at the end of “Young Goodman Brown,” when the Puritan minister in the forest explains the full consequence of the Calvinist understanding of Original Sin understood as total depravity:

“Welcome, my children,” said the dark figure, “to the communion of your race. Ye have found thus young your nature and your destiny. My children, look behind you!”

They turned and flashing forth, as it were, in a sheet of flame, the fiend worshippers were seen; the smile of welcome gleamed darkly on every visage.

“Lo,” the Puritan minister continued:

“there ye stand my children,” said the figure in a deep and solemn tone, almost sad with its despairing awfulness, as if his once angelic nature would yet mourn for our miserable race. “Depending on one another’s hearts, ye had still hoped that virtue were not all a dream. Now are ye undeceived. Evil is the nature of mankind. Evil must be your only happiness. Welcome again, my children to the communion of your race.”

“Young Goodman Brown” was Hawthorne’s attempt to deal with the psychological distortions that the Calvinist principle of total depravity had imposed on his ancestors. The classic American expression of this belief can be found in Jonathan Edwards’ famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” in which unregenerate man is compared to a spider dangling from a thin gossamer link over a fire. God is the only thing that keeps him from perdition. Because grace destroys nature without perfecting it, substance disappears beneath unregenerate man’s feet leaving him “nothing to stand on,” and “nothing between you and hell but the air” and “a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath, that you are held over in the hand of God,” hanging “by a slender thread.”…

[…] This is just an excerpt from the July-Aug 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

(Endnotes Available by Request)

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

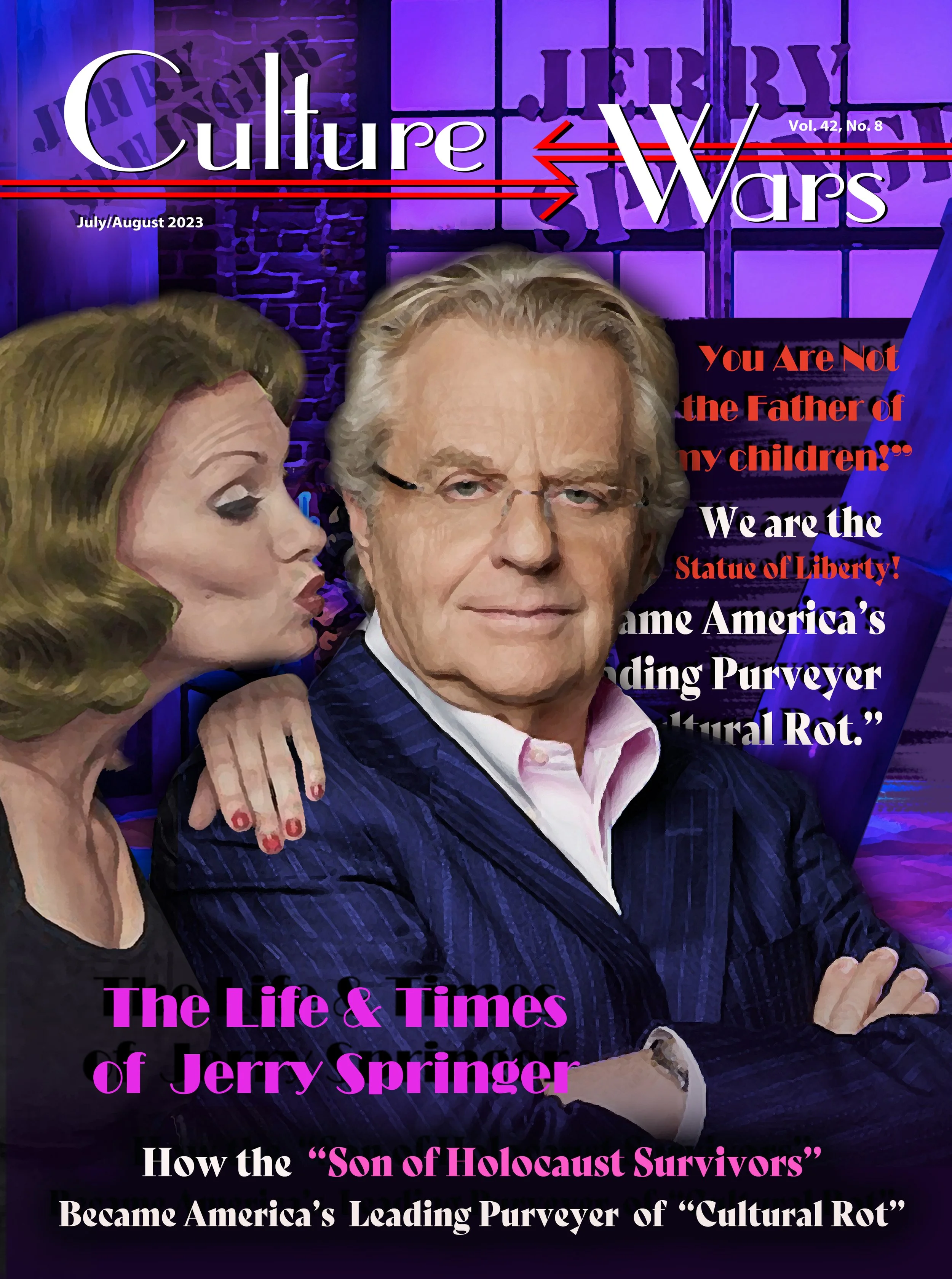

The Life and Times of Jerry Springer by Dr. James F. Tracy

The Hidden Grammar of the Dodger–Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Controversy by E. Michael Jones

Features

Why Hawthorne was Melancholy:

The “Lost Clew” Explained by E. Michael Jones

Reviews

The Beatific Vision by Lise Anglin

Endnotes

[i] Arlin Turner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, A Biography, (Oxford University Press, Printed in the United State, 1980), p. 393.

[ii] Cf. E. Michael Jones, Degenerate Moderns, “Stanley and Jane’s Excellent Adventure,” p. 79f.

[iii] Jones, Degenerate Moderns, pp. 83-4.

[iv] Perry Miller, “Jonathan Edwards to Emerson,” The New England Quarterly, December 1940, p. 606.

[v] Miller, p. 600.

[vi] Miller, p. 599.

[vii] Miller, p. 612.

[viii] Otto Bird and Katharine Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2005), p. 36.

[ix] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 56.

[x] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 39.

[xi] Marion Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, (La Salle, Illinois: Sherwood Sugden & Company Publishers, 1984), p. 30.

[xii] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 42.

[xiii] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 63.

[xiv] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 25.

[xv] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 24.

[xvi] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 24.

[xvii] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 115.

[xviii] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 120.

[xix] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 115.

[xx] Henry James, Hawthorne, (Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., Binghamton, NY, 1879 – Reprinted in 1956), p. 145.

[xxi] James, Hawthorne, p. 117.

[xxii] James, Hawthorne, p. 116-7.

[xxiii] James, Hawthorne, p. 125.

[xxiv] Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, or The Romance of Monte Beni, (Ohio State University Press, 1986), p. xx.

[xxv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xx.

[xxvi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xx.

[xxvii] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 118.

[xxviii] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 119.

[xxix] Bird, From Witchery to Sanctity, p. 116.

[xxx] The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/emerson/4957107.0001.001/80:9?page=root;size=100;view=text

[xxxi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 155.

[xxxii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxi.

[xxxiii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxi.

[xxxiv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxii.

[xxxv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxiv.

[xxxvi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxiii.

[xxxvii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxiii.

[xxxviii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxv.

[xxxix] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxv.

[xl] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxvi.

[xli] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 3.

[xlii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 3.

[xliii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 13.

[xliv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 39.

[xlv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 42.

[xlvi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 237.

[xlvii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 395.

[xlviii] Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, (The Riverside Press, Cambridge Mass, 1897), p. 395-6.

[xlix] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 401.

[l] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 240.

[li] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 233.

[lii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 235.

[liii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 246.

[liv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 246.

[lv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 79.

[lvi] Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, c2000), p. 43.

[lvii] Marx, The Machine in the Garden, p. 71.

[lviii] Marx, The Machine in the Garden, p. 76.

[lix] Marx, The Machine in the Garden, p. 116.

[lx] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxvii.

[lxi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 161.

[lxii] George McMichael, Concise Anthology of American Literature, ed. Frederick Crews (New York: Macmillan, c1993), p. 117.

[lxiii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 161.

[lxiv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 162.

[lxv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 162.

[lxvi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 208.

[lxvii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 209.

[lxviii] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 49.

[lxix] Johann Gottlieb Fichte, The Vocation of Man (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill, 1956), pp. 98-9.

[lxx] Montgomery, Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy, p. 70.

[lxxi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xl.

[lxxii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xli.

[lxxiii] Catechism of the Catholic Church, para. 774.

[lxxiv] Catechism of the Catholic Church, para. 774.

[lxxv] Catechism of the Catholic Church, para. 1455.

[lxxvi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 128.

[lxxvii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 129.

[lxxviii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 66.

[lxxix] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 154.

[lxxx] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 174.

[lxxxi] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 90.

[lxxxii] Theodore Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted (Milwaukee, Bruce Pub. Co. 1948), p. 84.

[lxxxiii] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 89.

[lxxxiv] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 393.

[lxxxv] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 61.

[lxxxvi] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 63.

[lxxxvii] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 61.

[lxxxviii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 286.

[lxxxix] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 258.

[xc] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 56-7.

[xci] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 57.

[xcii] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 59.

[xciii] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 93.

[xciv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxvii.

[xcv] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. xxxvii

[xcvi] Cf. E. Michael Jones, The Dangers of Beauty, p. 54ff.

[xcvii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 360.

[xcviii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 355.

[xcix] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 355.

[c] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 362.

[ci] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 369.

[cii] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 64-5.

[ciii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 369.

[civ] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 66.

[cv] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 66.

[cvi] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 66.

[cvii] Maynard, A Fire Was Lighted, p. 66.

[cviii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 352-3.

[cix] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 353.

[cx] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 353.

[cxi] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 357.

[cxii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 377.

[cxiii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 389.

[cxiv] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 392.

[cxv] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 389.

[cxvi] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 390.

[cxvii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 391.

[cxviii] Lathrop, Memories of Hawthorne, p. 391.

[cxix] James, Hawthorne, p. 127.

[cxx] Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, p. 123-4.

[cxxi] James, Hawthorne, p. 131.