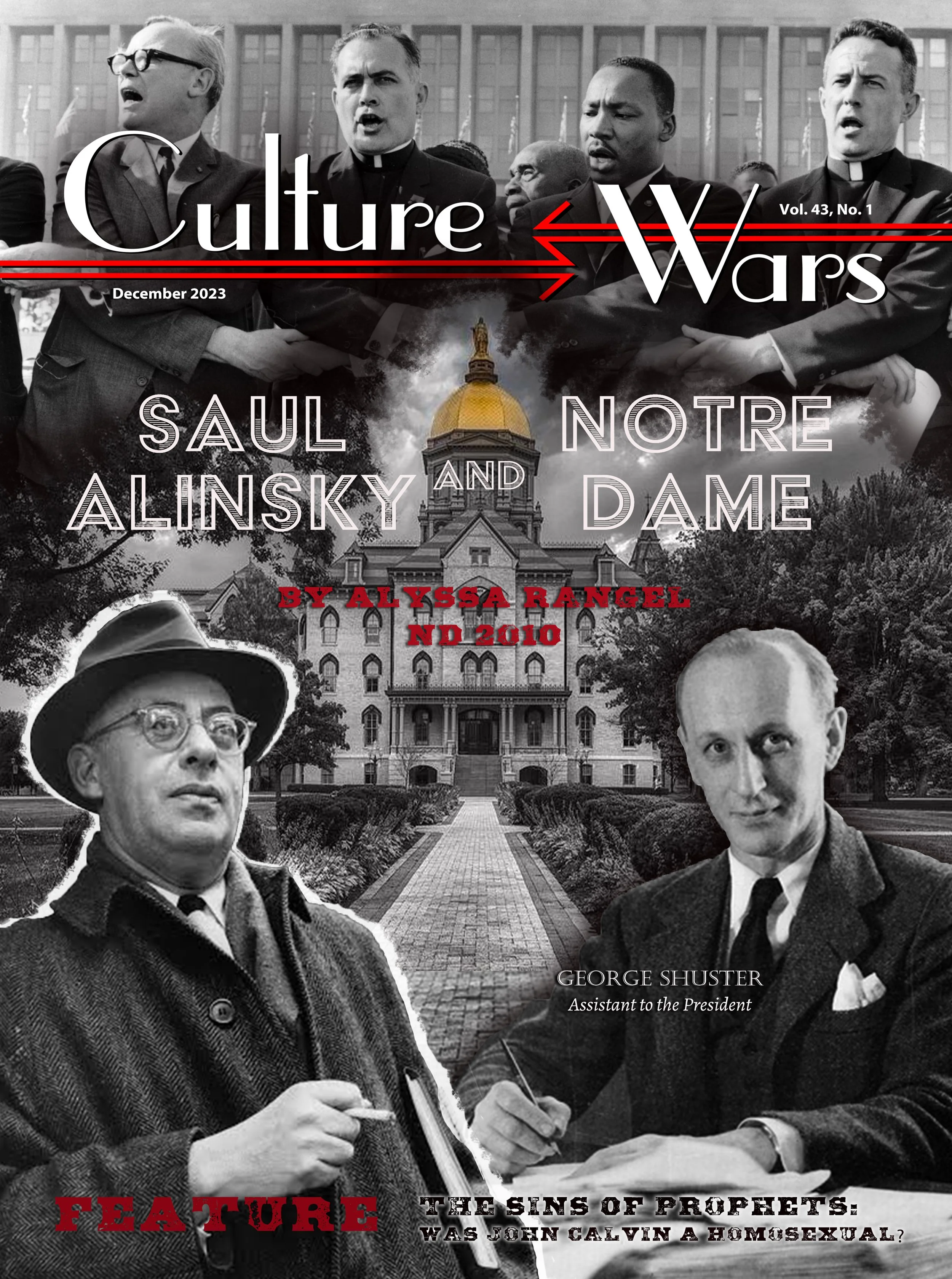

The Sins of Prophets: Was Calvin a Homosexual?

/Contemporary Evangelicals are sometimes surprised to learn that John Calvin considered himself a prophet. It stands in the way of the best Calvinist prooftexts against charismatic interpretations of spiritual gifts. For example, when Paul says, “As for prophecies, they will pass away; as for tongues, they will cease…” (1 Cor 13:8), we understand this to mean that these things will pass away at the end of the apostolic era, ca. 90 AD. Our interpretation of Corinthians corresponds well with the list of officers God has appointed for the building up of the church, namely “the apostles, the prophets, the evangelists, the shepherds and teachers” (Eph 4:11). The standard Reformed reading is that since the closing of the biblical canon, God no longer gives apostles or prophets because we have all that we will ever need to hear in the pages of Scripture. If Calvin was a prophet, we reason, might that imply that God is still giving prophets today? And if prophets, why not also Apostles? Problems abound.

Jon Balserak and Max Engammare have assembled a small mountain of evidence to demonstrate that Calvin considered himself to be a prophet, as did those around him. Consider the words of Calvin’s successor and friend, Theodore Beza, reflecting on Calvin’s death:

The following night, and the day after as well, there was much weeping in the city. For the body of the city mourned the prophet of the Lord, the poor flock of the Church wept the departure of its faithful shepherd, the school lamented the loss of its true doctor and master, and all in general wept for their true father and consoler, after God.[i]

The title was more than honorific, and it included divinely inspired predictions. When calamities arrived on the heels of Calvin’s warnings about God’s coming judgment, Beza concluded that his mentor had “announced this by a prophetic spirit.” He clarified that Calvin was not using astrology (the common way to tell the future), but that he was led by the same spirit through whom “Luther foresaw and the sufferings that were about to fall on all Germany because of their contempt of the Word.”[ii]

Calvin, too, wrote of his prophetic role when he compared himself to the prophets of old:

Isaiah and Micah… and Hosea and Amos… undertook what God had committed to his charge; thus each confined himself within the limits of his own call and office. For if we, who are called to instruct the Church, close our eyes to the sins which prevail in it, and neglect those whom the Lord has appointed to be taught by us, we confound all order.[iii]

Calvin speaks about the biblical prophets as both models and peers. Calvin’s concept of his own prophetic role can also be seen in his handling of the New Testament. Bruce Gordon arrives at the same conclusion as Balserak by assessing Calvin’s use of Paul. In his magisterial biography, Gordon argues that “through intensive study, prayer, and conduct Calvin sought to become Paul.”[iv] He concludes that, “through his absolute confidence in his ability to interpret Paul, Calvin was certain that he could be the voice of the Apostle in his own age.”[v]

But Calvin was hardly an anomaly in this regard. Martin Luther, the founder of the Reformation, repeatedly called himself a prophet. In 1539 he confided to a friend that, “I don’t like prophesying, and I also don’t want to prophesy, because what I prophesy—especially the evil—occurs more than I like… Because I speak God’s word, it has to happen.”[vi] In spite of his professed dislike for prophesying, inspired predictions were not at all out of place in Luther’s daily life. In January 1532, Luther “foretold that he would be sick, that in March he would be overtaken by a grave illness.” It overcame him shortly afterward, on January 22, which a friend took as a confirmation of Luther’s prophetic powers. The illness was severe enough that those closest to him could be heard speaking anxiously about how happy Rome would be if he were to die. “But I am not going to die now,” Luther retorted from his sickbed: “I know this of a certainty.”[vii] Naturally enough, Luther’s subsequent recovery was taken as further confirmation that he was a prophet.

Other prophets were arising at the same time in Europe, particularly in another movement in Switzerland under the leadership of Ulrich Zwingli, the father of Reformed Protestantism. “I too put my hand to the plough” Zwingli later wrote, “and raised my voice.”[viii] If anything, Zwingli was even more interested in his own prophetic call than Luther, almost to the point of obsession. Zwingli argued that every minister was a prophet, “responsible for society,” and that he was “a defender of divine righteousness, standing together with the magistrate, who oversaw the laws of the state. This was the role of the ancient prophets of Israel, as restored in Zurich.”[ix] In 1525 Zwingli established a consortium of preachers which he called the Prophezei. In doing so he “placed prophecy at the heart of the new Church.”[x]

Although Calvin constantly downplayed his relationship to Zwingli, Bruce Gordon, who has written the definitive biographies of both reformers, concludes that they are inherently bound together. It was Zwingli who “imagined and created a new form of Christianity grounded in the covenantal relationship between God and humanity and founded on the positive understanding of divine law.”[xi] Yes, Calvin shaped much of the way we view that covenant today, but “the shape and cadence of Reformed Christianity came from Zurich.”[xii]

Competing Mouthpieces

It might be tempting to write off their prophetic claims as a bizarre eccentricity, but for the reformers, the prophetic office was essential to their whole project. The reason lies in their self-conscious awareness that, by breaking with Rome, they had effectively set themselves on an interpretive island which diminished their claims to speak for God. We do not immediately see this problem today, largely because nearly every evangelical Christian has made the claim that “the Spirit told me to do X.” In other words, nearly all contemporary Christians believe that they are prophets.

But the reformers saw the great problem of authority with perfect clarity: If they could not trace a clear line of consistent interpretation of Scripture from the Apostles to themselves, including highly esteemed authorities like Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, Anselm of Canterbury, and Bede, then how could they claim to be authorities? Therefore, they had to conceive of their own actions as being part of a different line, that did not stand on the unbroken heritage of faithful medieval theology. They had to be God’s gift to a Church which had increasingly abandoned Him, to the point where He had to send new prophets to call us back.

The need for a compelling “succession narrative” has long been mocked by Protestants as a unique problem of the Roman Catholic Church, whose list of supreme Pontiffs includes known lechers and debauchers. Yet, the same need was felt acutely by the reformers, which is why they were so careful to draw lines of orthodoxy that included only those other reformers who agreed with the most important tenets of their theology.

Because Zwingli and Luther were both prophets, each had to be right, especially if they disagreed. Not long after they learned of each other, each one began “casting the other in the role of Satan’s minion and breaker of the body of Christ.”[xiii] In his 1525 treatise, “Against the Heavenly Prophets,” Luther said Zwingli was “perverted” and “lost to Christ.” “I testify on my part that I regard Zwingli as un-Christian,” he wrote with characteristic zeal, “with all his teachings, for he holds and teaches no part of the Christian faith rightly. He is seven times worse than when he was a papist.”[xiv] By 1526, Luther wrote two prefaces in which he called Zwingli a false prophet, who was “in league with the devil.”[xv]

At their fateful meeting in 1529, spurred by pressure from their mutual benefactor, Philip of Hesse, to present a united front against Rome, Luther and Zwingli agreed on fourteen theological points, but they could not agree on the final one. Martin Luther then famously (and spuriously) carved “This is my body” into a table in order to highlight the difference between their theology of the Lord’s Supper. Luther told Zwingli to “submit” to the “clear words” of Scripture, and concluded that “God has blinded [the Reformed]” to the truth.[xvi] Zwingli “does not take religion seriously.”[xvii] Zwingli and his ilk “are the enemies of Christ’s cross” Luther wrote in 1531, “whose glory is in confusion.”[xviii]

When word spread in October that year that Zwingli had died in a battle he had waged as a prophet, the response was mixed. In Zurich, Zwingli’s successor and biographer, Heinrich Bullinger, argued that Zwingli was not just a prophet, but rather THE true prophet of God. “In this man” said the heir apparent, “one found once and for all and absolutely what one had sought among the true prophets of God.”[xix]

Up north, Luther found no time to mourn. “I was a prophet” Luther wrote to a friend in January 1532, “when I said that God would not long tolerate these rabid and furious blasphemies of which those people were full, ridiculing our ‘breaded’ God, calling us carnivores and blood drinkers… [and] other horrible names.”[xx] The closest Luther came to expressing condolences was an allusion to St. Paul’s sentiment in Romans 9: “I wish from my heart Zwingli could be saved, but I fear the contrary; for Christ has said that those who deny him shall be damned.”[xxi]

In other words, Luther excommunicated Zwingli and the rest of the Protestants who were not Lutherans. This fact must be understood in order to comprehend why it is so perfectly logical for conservative Lutheran churches (e.g. LCMS, WELS) to give the Eucharist only to members of churches in their own denominations. For them, as for Luther, only those with a correct view of communion are true Christians. It also explains why early 20th century ecumenism necessarily involved the watering down of doctrine: because in order to reunify the churches of the world, each one had to give up the very claim on which they based their perpetual authority, namely that they alone were the true church.[xxii] The bottom line is that the reformers realized that they needed to be true Prophets in order not to be true heretics.

Zwingli & Luther as scoundrels

Unfortunately for Zwingli, there were always good reasons to question his credentials as a prophet of God. In 1506, at 22 years old, Zwingli became the priest of a remote Alpine village named Glarus, where according to Gordon, “he came to enjoy the company of women and the pleasures of sex.”[xxiii] Gordon notes that “while quasi-clerical marriages were pretty much the norm, Zwingli seems… to have been more promiscuous.”[xxiv] He carried his habits with him to his next post in Einsiedeln, where he was again, “sexually active – even highly active.”[xxv] He later insisted that, “he had never slept with a married woman, a virgin or a nun; he did not mention prostitutes, on whom the rumors focused.”[xxvi]

When Zwingli was being considered for a position as priest in Zurich in 1518, he had to address a rumor that he had seduced a nobleman’s daughter. Zwingli responded with a mixture of honesty, minimization, and victimhood. “I made a firm resolution” he begins, “not to interfere with any female… [but] that did not turn out very well…”[xxvii] In his defense, Zwingli clarifies that the girl in question was in no way noble: “No one doubts that the lady concerned is the barber’s daughter except possibly the barber himself who has often accused his wife, the girl’s mother, a supposedly true and faithful wife, of adultery…”[xxviii] He admits that this was not the first time, but “when I was still in Glarus and let myself fall into temptation in this regard a little.” However, he assures, “I did so so quietly that even my friends hardly knew about it.”[xxix] It seems more than a little unlikely that such sins could remain secret in a mountain village with just one priest.

But the most recent case was a notoriously loose woman: “In this instance it was a case of maiden by day, matron by night.”[xxx] Her character was bad enough that “everybody in Einsiedeln knew about her… [and] no one in Einsiedeln thought I had corrupted a maiden. All the girl’s relations knew that she had been caught long before I came to Einsiedeln, so that I was not in any way concerned…”[xxxi] Zwingli’s conscience was clear. In the end, he got the job in large part because his main competitor was living in concubinage with multiple children. Once in Zurich, Zwingli took up with a widow named Anna, who he officially married six year later, in 1524, “three months before the birth of their first child.”[xxxii]

How, we might wonder, did this man ever become a leader of the Reformation? Not only was he a leader, but from a chronological standpoint he preceded Luther in his insistence on Scripture alone, and on the inefficacy of indulgences. Is it possible that Zwingli’s extreme promiscuity preceded his conversion to the Gospel that made him famous? Zwingli insisted that his fundamental conversion was complete as far back as his schooldays in Basel, 1505, when he learned “for the first time that the death of Christ was once offered for our sins, by which we have been saved.”[xxxiii] Therefore, his conversion to the theology of the Reformation preceded his entire career as a priest.

There does not seem to have been any dramatic change in Zwingli’s character after his arrival in Zurich, although he eventually married his concubine when he finally threw off the last vestiges of the priesthood. Zwingli’s constant warring, first with Luther over doctrine, and later on the actual battlefield, leads one to suspect that he never truly submitted his base appetites to God, but instead channeled them into other areas of life. Martin Luther’s sexual deviance was also notorious and scarcely concealed. As I considered this, I wondered if there might be a correlation between breaking with Rome, doggedly insisting that you speak for God, and sexual deviance, so I decided to take a second look at the theological founder of my own Presbyterian denomination, John Calvin…

[…] This is just an excerpt from the Dec 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

The Demise of the Last Jewish Kingdom by E. Michael Jones

Features

The Sins of Prophets: Was Calvin a Homosexual? by Pastor Anonymous

Reviews

Saul Alinsky and Notre Dame by Alyssa Rangel

(Endnotes)

[i] Quoted in Max Engammare, “Calvin: A Prophet without a Prophecy” (Church History 67:4, 1998), p. 643. [ii] ibid., p. 644. [iii] Quoted in Jon Balserak, “‘There will always be prophets’: Deuteronomy 18:14–22 and Calvin’s prophetic awareness” (in ed. H. J. Selderhuis, Calvin - Saint or Sinner? Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation: Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation. Vol. 51. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010.), p. 88. [iv] Bruce Gordon, Calvin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 110. [v] ibid. [vi] Translated from German and quoted in Marcus Sandl, “Precarious Times: The Discourse of the Prophet in the Age of Reformation,” in Temporality and Mediality in Late Medieval and Early Modern Culture, (ed. by Christian Kleining and Martina Sterken Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2018 [197–228]), 220. [vii] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 54: Table Talk (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 54; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 23. [viii] Gordon, F. Bruce. Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet. Yale University Press. Kindle Edition, 150. [ix] ibid., 144. [x] ibid., 144. [xi] Gordon, Zwingli, 7. [xii] ibid. [xiii] ibid., 174. [xiv] Quoted in Gordon, Zwingli, 175-176. [xv] Quoted in Gordon, Zwingli, 174. [xvi] Oberman, 237. [xvii] Bainton, 206. [xviii] Gordon, Zwingli, 259. [xix] Gordon, Zwingli, 261. [xx] Gordon, Zwingli, 260. [xxi] Gordon, Zwingli, 259. [xxii] Bonhoeffer pointed out the paradox of those American denominations who do not really believe in their own historically exclusive claims to orthodoxy in his essay, “Protestantism without Reformation.” [xxiii] Gordon, Zwingli, 34. [xxiv] Ibid., 35. [xxv] Ibid., 42. [xxvi] Ibid., 42. [xxvii] Denis Janz, ed., A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1999), 152. [xxviii] ibid. [xxix] ibid. [xxx] ibid. [xxxi] ibid. [xxxii] Gordon, Zwingli, 69. [xxxiii] Bullinger, quoted in Gordon, F. Bruce. Zwingli (p. 18). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition. [xxxiv] Quoted in Bernard Cottret’s Calvin: A Biography (London: Continuum International Pub. Group, 2003, Kindle Edition), Kindle Location 40. [xxxv] Gordon, 18. [xxxvi] ibid., 46. [xxxvii] ibid., 63. [xxxviii] Cottret, Calvin, Kindle Location 70. [xxxix] Alister E. McGrath, A Life of John Calvin: A Study in the Shaping of Western Culture (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 13–14. [xl] ibid., 14. [xli] ibid., 15. [xlii] ibid., 16. [xliii] ibid. [xliv] John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, Edited by James Anderson in Calvin’s Commentaries (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1949), xliii. [xlv] Ibid. [xlvi] Paker, Portrait, 82. [xlvii] Parker, 83. [xlviii] Ibid. [xlix] Parker, Protrait, 84. [l] McGrath, 17. [li] McGrath, 17. [lii] T.H.L. Parker, Portrait of Calvin, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Desiring God, 2008), 125. [liii] Quoted in Engammar, “John Calvin’s Seven Capital Sins” in Selderhuis, H. J., ed. Calvin - Saint or Sinner? (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation: Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation 51. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 28. [liv] James Atkinson, The Great Light: Luther and Reformation (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1968), 172. [lv] Cottret, Kindle Location 323. [lvi] François Wendel, Calvin: The Origins and Development of His Religious Thought (trans. by Philip Mairet, New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 23. [lvii] Cottret, Kindle Location 355-356. [lviii] Cottret, Kindle Location 198-199. [lix] Parker, T.H.L., John Calvin: a Biography (Louisville, KY, Westminster John Knox: 2006), 199–203. [lx] Gordon, 33–35. [lxi] Parker, Portrait, 36–37. [lxii] Collin Hanson, Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2023), xii. [lxiii] Gordon, 6. [lxiv] Cottret, 227, Kindle Edition. [lxv] Quoted in Cottret. Calvin: A Biography (Kindle Locations 253-254). [lxvi] Cottret, 259-265, Kindle Edition. [lxvii] Gordon, 6. [lxviii] Since “Sodomy” was an unnamable sin, words like “heresy” or “Lutheran” were frequently used interchangeably. See Helmut Puff, Sodomy in Reformation Germany and Switzerland, 1400-1600. (Chicago Series on Sexuality, History, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 13–14, 47. [lxix] See Heiko Oberman, Harvest of Medieval Theology. The proliferation of nominalism had long since evoked theological discussions about the nature of justification, and Luther seems to have learned his own view largely from his mentor, Staupitz, who died a Catholic in good standing. See also Oberman’s Luther: Man between God and the Devil. Luther admitted that “Staupitz laid all the foundations” for his theology (quoted in Luther, 144), and Staupitz preached about the joyful exchange between Christ and the sinner wherein Christ becomes “unjust and a sinner” in the sinner’s place (quoted in Luther, 184). [lxx] See Oberman, Luther, 283–289. See also Thomas A. Fudge, “Incest and Lust in Luther’s Marriage: Theology and Morality in Reformation Polemics.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 34, no. 2 (2003): 319–45. See also Helmut Puff, Sodomy in Reformation Germany and Switzerland, 1400-1600 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp. 155–156. [lxxi] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 36: Word and Sacrament II (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 36; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 103–106. [lxxii] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 45: The Christian in Society II (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 45; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 22. [lxxiii] ibid., 23. [lxxiv] ibid., 23–24. [lxxv] ibid., 24. [lxxvi] ibid., 25. [lxxvii] Martin Luther, Luther’s Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters (Ed. by Preserved Smith andCharles M. Jacobs. vol. II, 1521–1530, 1918 Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society,) letter 672, pp. 305–6. [lxxviii] Oberman, 276. [lxxix] ibid., 284 [lxxx] ibid., 286. [lxxxi] Karl F. Ledderhose, The Life of Philip Melanchthon (trans. by Gottlob Krotel; Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1857), 171. [lxxxii] Oberman, 286. [lxxxiii] ibid., 287. [lxxxiv] Ledderhose, 173. [lxxxv] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 54: Table Talk (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 54; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 388. [lxxxvi] See for example, Calvin’s fears about Farel’s marriage to a girl 50 years his junior, which will be discussed later (Gordon, Calvin, 281). [lxxxvii] See, for example, Puff, Sodomy, 13 [lxxxviii] Diarmaid MacCulloch, “Reformation Time and Sexual Revolution.” (New England Review 24:4, 2003), 28. [lxxxix] See Marian Hillar and Claire S. Allen, Michael Servetus: Intellectual Giant, Humanist, and Martyr (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2002), 19. [xc] Gordon, Calvin, 43. [xci] ibid. [xcii] Puff, Sodomy, 117–18, 125–28. The phrase “Italian wedding” meant anal sex (127). Luther noted that every county has its vice: Greeks are “whorers,” Italians are sodomites (127). As we have already seen, he regarded Czechs as gluttons, Germans as drunkards, and Wends (Slavs who lived in today’s NE Germany) as thieves. [xciii] Ibid., 43. [xciv] Ibid., 217. [xcv] Merrick Whitcomb, ed. “The Complaint of Nicholas de La Fontaine Against Servetus, August 14, 1553.” In Period of the Later Reformation, Vol. 3. Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania History Department, 1898. [xcvi] Masten, Jeffrey. “Bound for Germany: Heresy, Sodomy, and a New Copy of Marlowe’s Edward II.” TLS. Times Literary Supplement, no. 5725–5726 (December 21, 2012): 17–20. [xcvii] Wendel, Calvin, 24. [xcviii] Alvan Bregman, Emblemata: The Emblem Books of Andrea Alciato (Newtown, PA: Bird & Bull Press, 2007), 7; Mr. Bernard Cottret. Calvin: A Biography (Kindle Location 323). Kindle Edition; “Andrea Alciato unwittingly invented the genre in 1531 with the publication of his little booklet of illustrated epigrams, the Emblematum liber, emblem books were exceedingly popular.” Christopher Wild, “‘A Just Proportion of Body and Soul’: Emblems and Incarnational Grafting.” In Image and Incarnation, 231–50. Brill, 2015. (p. 231) [xcix] Quoted in Bregman, 30. [c] “Andrea Alciati dedicated his Emblematum Liber, the oldest book of emblems, to Peutinger, who published the work in 1531” Künast, Hans-Jörg. Two Volumes of Konrad Peutinger in the Beinecke Library.T The Yale University Library Gazette 77, no. 3/4 (2003): 133–42, p. 137. [ci] Arthur C. McGiffert, Martin Luther, the Man and His Work. (New York: The Century Co., 1919), 118. [cii] Borghesi, Francesco, and Giorgia Alù. Introduction: Between Word and Image, East and West.I Literature and Aesthetics 22, no. 2 (January 1, 2012): 1–12, p. 4. [ciii] “Alciato did not give frequent statements on his emblem poetics or on his sources. One remark he made on 9 January 1523, on his first collection of Emblemata, however, seems to be of great interest: ‘These past Saturnalia, in order to gratify the noble Ambrogio Visconti, I put together a little book of epigrams to which I gave the title Emblems (Emblemata), for in each epigram I describe something (aliquid describo) which is taken from history (ex historia) or from nature (ex rebus naturalibus) and means (significet) something refined (aliquid elegans), from which painters, goldsmiths, and metalworkers, can fashion the kind of objects which we call badges (scuta) and which we attach to our hats or use as personal devices (signs; insignia), like Aldus’ anchor, Froben’s dove or Calvo’s elephant which is labouring so long but gives birth to nothing.’” Enenkel, Karl A. E. “The Emblematization of Nature, and the Poetics of Alciato’s Epigrams.” In The Invention of the Emblem Book and the Transmission of Knowledge, ca. 1510–1610, 3–124. Brill, 2018. (p. 4) [civ] Kenneth Borris, ed. Same-Sex Desire in the English Renaissance: A Sourcebook of Texts, 1470-1650. New York: Routledge, 2004. (p. 40–43) [cv] See Rebecca Zorach, “The Matter of Italy: Sodomy and the Scandal of Style In Sixteenth-Century France.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 28:3 (1998), 581–609. [cvi] Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence (Oxford: OUP, 1996), 191. [cvii] Rocke, 140. [cviii] Rocke, 140. [cix] Helmut Puff, Sodomy in Reformation Germany and Switzerland, 1400-1600 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), e.g. 43, 117. [cx] Wendel, 24. [cxi] Coleman Phillipson, “Andrea Alciati and His Predecessors” (Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation 13:2 (1913): 245–64,) 258. [cxii] Lucia Floridi, “The Construction of a Homoerotic Discourse in the ‘Epigrams’ of Ausonius.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 108 (2015): 545–69. [cxiii] Floridi, 549–550. [cxiv] Floridi, 550-51. [cxv] Floridi, 549. [cxvi] “EMBLEM LITERATURE ALCIATI ANDREA Emblematum Libellus 1540.” Accessed July 22, 2023. https://catalogue.swanngalleries.com/Lots/auction-lot/EMBLEM-LITERATURE--ALCIATI-ANDREA--Emblematum-libellus-1540-?saleno=2457&lotNo=107&refNo=735782. [cxvii] Giovanni Dall’Orto, “Fidentian Poetry” in Encyclopedia of Homosexuality (edited by Wayne R. Dynes. New York: Garland, 1990), 387. [cxviii] John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 1980, anniversary edition 2015), 252-253. See also Rocke, 136. [cxix] Puff, 72–72. [cxx] Puff, 138. [cxxi] Mr. Bernard Cottret. Calvin: A Biography (Kindle Locations 358-359). Kindle Edition. [cxxii] Mr. Bernard Cottret. Calvin: A Biography (Kindle Locations 364-366). Kindle Edition. [cxxiii] Michael Jinkins, “Theodore Beza: Continuity and Regression in the Reformed Tradition” (Evangelical Quarterly 64:2 (September 6, 1992): 131–54.), 132 [cxxiv] Wright, Beza. [cxxv] Wright, Beza. [cxxvi] Henry M. Baird, Theodore Beza: The Counsellor of the French Reformation, 1519-1605. (New York: Putnam, 1899), 27. (Par désir de gloire et pour contenter les vux duun maitre à qui je devais tout, je fus entrainé à publié ce petit livre. [cxxvii] Wright, Beza. [cxxviii] Wendel, 106. [cxxix] Parker writes that “as a boy [Beza] lived in the same house with him in Bourges,” Portrait, 32. [cxxx] Henry Baird, Theodore Beza: The Counsellor of the French Reformation (New York: Putnam, 1899), p. 25. [cxxxi] Shawn D. Wright, Theodore Beza: The Man and the Myth (London: Christian Focus, 2015), e-book. [cxxxii] Baird, p. 25. So also David C. Steinmetz, Reformers in the Wings: From Geiler von Kaysersberg to Theodore Beza. Oxford University Press, 2001. [cxxxiii] Scott M. Manetsch, Theodore Beza and the Quest for Peace in France, 1572-1598 (Leiden: Brill Academic, 2021), 422 [cxxxiv] Barbara Sher Tinsley, Pierre Bayle’s Reformation: Conscience and Criticism on the Eve of the Enlightenment. (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 2001), p. 244. [cxxxv] Laurie Langbauer, The Juvenile Tradition: Young Writers and Prolepsis, 1750-1835 (Oxford: OUP, 2016), p. 67. [cxxxvi] Anne Lake Prescott, “English Writers and Beza’s Latin Epigrams: The Uses and Abuses of Poetry.” Studies in the Renaissance 21 (1974): 83–117, p. 85. [cxxxvii] Winfried Schleiner, “That Matter Which Ought Not To Be Heard Of,” Journal of Homosexuality 26:4 (1994): 41–75, p. 44. See also, Diarmaid MacCullogh, “Reformation Time and Sexual Revolution.” New England Review 24:4 (2003): 6–31, esp. p. 24. [cxxxviii] Schleiner, p. 44. [cxxxix] Quoted in Henry Baird’s, favorable biography by Theodore Beza: The Counsellor of the French Reformation, 1519-1605. (New York: Putnam, 1899), p. 28. [cxl] Wright, so also Baird. [cxli] Prescott, 85. [cxlii] Wright. [cxliii] This is the root experience of schizophrenia—which is a division (schizo) of the mind (phren). [cxliv] Wendel, 24. [cxlv] See for example, Simonetta Carr, Marguerite dMAngoulême, an Influential Reformer,” A Place for Truth, May 31, 2022. Subby Szterszky, “Women of the Reformation: Marguerite de Navarre,” Focus on the Family Canada, 2021. Rebecca VanDoodewaard, “Reformation Women: Marguerite de Navarre,” Tabletalk, January 8, 2020. [cxlvi] Robert W. Bernard, “Platonism - Myth or Reality in the Heptameron?” (The Sixteenth Century Journal 5:1 (1974): 3–14), p. 3. [cxlvii] Sylvie L. F. Richards, “The Burning Bed: Infidelity and the Virtuous Woman in ‘Heptameron’ XXXVII.” (Romance Notes 34:3 (1994): 307–15), p. 307. [cxlviii] See for example, Dora Polachek, “Scatology, Sexuality and the Logic of Laughter in Marguerite de Navarres Heptaméron,” Medieval Feminist Forum 33 (March 1, 2002): 30–42. [cxlix] Marguarite of Navarre, Tales Of The Heptameron, trans. by George Saintsbury, Project Gutenberg ebook, 2006. [cl] Scott Francis, “Scandalous Women or Scandalous Judgment? The Social Perception of Women and the Theology of Scandal in the Heptaméron (L Esprit Créateur 57:3 (2017): 33–45), 42. [cli] Marguarite Of Navarre. [clii] Nora Martin Peterson, “What Women Know: The Power of ‘Savoir’ in Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptaméron” (LEsprit Créateur 57, no. 3 (2017): 21–32), 29. [cliii] See also Deborah N. Losse, “Distortion as a Means of Reassessment: Marguerite De Navarre’s Heptameron and the ‘Querelle Des Femmes,’” Journal of Rocky Mountain Medieval and Renaissance Assocation 3 (1982): 75–84. [cliv] Gordon, Alexander. “Farel, Guillaume.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10, 1911. Wikisource. [clv] Herbert D. Foster, “Geneva Before Calvin (1387-1536): The Antecedents of a Puritan State,” The American Historical Review 8:2 (1903), 222–23. [clvi] Gordon, Alexander. “Farel, Guillaume.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10, 1911. Wikisource. [clvii] Herbert D. Foster, “Geneva Before Calvin (1387-1536): The Antecedents of a Puritan State,” The American Historical Review 8:2 (1903), 222–23. [clviii] ibid., 223. [clix] Herbert Darling Foster notes that, at this time, “France had also espoused the Genevan cause to check Savoy,” in “Calvin’s Programme for a Puritan State in Geneva, 1536-1541,” Harvard Theological Review 1:4 (1908), 402. [clx] Parker, Portrait, 36–37. [clxi] Foster, “Antecedents,” 224, footnote 2. [clxii] ibid., 224, footnote 2. [clxiii] ibid., 224, footnote 2. [clxiv] ibid., 222. [clxv] “The scheme of the placards was proposed. Farel undertook the task.” Willaim M. Blackburn, William Farel, and the Story of the Swiss Reform (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1865), 286. [clxvi] French title of the poster: “Articles véritables sur les horribles, grans et importables abuz de la messe papale, inventée directement contre la Sainte Cène de notre Seigneur, seul médiateur et seul Sauveur Jésus-Christ”. [clxvii] ibid., 225, footnote from 224. [clxviii] ibid., 225, footnote from 224. [clxix] ibid. [clxx] ibid. [clxxi] ibid. [clxxii] ibid., 225. [clxxiii] Quoted in ibid., 225. [clxxiv] Quoted in ibid., 226. [clxxv] McGrath, 92. [clxxvi] McGrath, 93. [clxxvii] Quoted in Foster, “Programme,” 402. [clxxviii] Quoted in Foster, “Antecedents,” 229. [clxxix] Calvin, Psalms, xlii. [clxxx] ibid. [clxxxi] He called them “perverse et meschant,” as quoted in Kingdon, 162. [clxxxii] Frans Pieter van Stam, “The Group of Meaux as First Target of Farel and Calvin’s Anti-Nicodemism.” (Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 68:2, 2006), 254, fn. 8. [clxxxiii] Kingdon, 162. [clxxxiv] Herbert Darling Foster, “Calvin’s Programme for a Puritan State in Geneva, 1536-1541,” The Harvard Theological Review 1:4 (1908), 391. [clxxxv] Summarized and quoted in Foster’s, “Programme,” 407. [clxxxvi] Quoted in Forster, “Programme,” 408. [clxxxvii] Gordon, 79. [clxxxviii] Gordon, 79. [clxxxix] Gordon, 79. [cxc] Parker, 45. [cxci] John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, Edited by James Anderson in Calvin’s Commentaries (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1949), xliii. [cxcii] Heiko Oberman, “Calvin and Farel: The Dynamics of Legitimation in Early Calvinism.” (Reformation & Renaissance Review 1, 1999), 11. [cxciii] Ibid. [cxciv] Quoted in William M. Blackburn, William Farel, and the Story of the Swiss Reform (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1865), 344. [cxcv] Gordon, Calvin, 281. [cxcvi] Gordon, Calvin, 282. [cxcvii] Gordon, Calvin, 296. [cxcviii] Philip Benedict, Season of Conspiracy: Calvin, the French Reformed Churches, and Protestant Plotting in the Reign of Francis II (1559-60) (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press, 2020), 1. Philip Benedict is an American-born professor of history and former director of the Institute for the History of the Reformation at the University of Geneva. In a monograph from in 2020, Benedict demonstrates conclusively that this was a well-planned attempt to ignite a revolution. This fact has been known to scholars since Alain Dufour first demonstrated it in 1963 by analyzing the correspondence between the Geneva ministers, though it has been carefully ignored by all popular biographers. [cxcix] ibid., 3. [cc] Cottret, Calvin, 132 (Kindle Edition). [cci] Oberman, “Calvin and Farel,” 15. [ccii] John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, Edited by James Anderson in Calvin’s Commentaries (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1949), xliii. [cciii] John Witte, Jr., “Anglican Marriage in the Making: Becon, Bullinger, and Bucer,” in The Contentious Triangle: Church, State, and University, edited by George Huntston Williams, Rodney Lawrence Petersen, and Calvin Augustine Pater, 243–61. (Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies, Kirksville, Mo.: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1999), 253. [cciv] Selderhuis, Bucer, 173. [ccv] Heilke, Thomas. “Friendship in the Civic Order: A Reformation Absence.” In Friendship & Politics: Essays in Political Thought, edited by John von Heyking and Richard Avramenko, 163–95. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008. [ccvi] H. J. Selderhuis, Marriage and Divorce in the Thought of Martin Bucer (Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies. Kirksville, Mo.: Thomas Jefferson University Press at Truman State University, 1999), 145–148. [ccvii] De Regno Christi, quoted in Witte, Jr., 254. [ccviii] De Regno Christi, quoted in Witte, Jr., 255. [ccix] De Regno Christi 210, quoted in Selderhuis, 265. [ccx] De Regno Christi, quoted in Witte, Jr., 255. [ccxi] De Regno Christi, quoted in Witte, Jr., 255. [ccxii] De Regno Christi, quoted in Witte, Jr., 256. [ccxiii] Bucer, De Regno Christi, quoted in Not in God’s Image: Women in History from the Greeks to the Victorians, edited by Julia O’Faolain, and Lauro Martines (Harper Colophon Books. New York: Harper & Row, 1973), 201. [ccxiv] Burcher’s “Letter to Heinrich Bullinger June 8, 1550.” Quoted in H. J. Selderhuis, Marriage and Divorce in the Thought of Martin Bucer (Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies. Kirksville, Mo.: Thomas Jefferson University Press at Truman State University, 1999), 1. [ccxv] Herman Selderhuis, “Luther and Calvin,” (SBJT 21:4 (2017): 145-162), 147. [ccxvi] ibid. [ccxvii] ibid. [ccxviii] ibid. [ccxix] ibid., 148. [ccxx] ibid. [ccxxi] ibid. [ccxxii] Quoted in Gordon, p. 87. [ccxxiii] ibid. [ccxxiv] Gordon, pp. 87–88. [ccxxv] Gordon, p. 88. [ccxxvi] Gordon, p. 88. [ccxxvii] McGrath, 72. [ccxxviii] McGrath, 73. [ccxxix] Gordon, 42. [ccxxx] McGrath, 74. [ccxxxi] Gordon, 46. [ccxxxii] Théodore Bèze, The Life of John Calvin (trans. by Francis Sibson; Philadelphia: Whetham, 1836), 153. [ccxxxiii] Quoted from CO 37:480 in Jon Balserak, “John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet” (Oxford: OUP, 2014), 179. [ccxxxiv] Gordon, Calvin, 212–213. See also Bèze, The Life of John Calvin, 153. [ccxxxv] Gordon, Calvin, 205. [ccxxxvi] McGrath, 16–17. [ccxxxvii] Bèze, The Life of John Calvin, 153. [ccxxxviii] Peter Marshall, “John Calvin and the English Catholics, c. 1565-1640,” (The Historical Journal 53:4, 2010), 855. [ccxxxix] Ibid., 857. [ccxl] Jeffrey Masten, “Bound for Germany: Heresy, Sodomy, and a New Copy of Marlowe’s Edward II,” Times Literary Supplement (December 21, 2012): 17–20. [ccxli] Masten, 18. [ccxlii] Wilson, John. A Treatise of Religion and Government with Reflections Upon the Cause and Cure of England’s Late Distempers and Present Dangers: The Argument Whether Protestancy Is Less Dangerous to the Soul, or More Advantagious to the State, Then the Roman Catholick Religion? The Conclusion That Piety and Policy Are Mistaken in Promoting Protestancy, and Persecuting Popery by Penal and Sanguinary Statuts. London, 1670. [ccxliii] Clark, R. Scott. “Was Calvin A Homosexual Convict? - The Heidelblog.” Https://Heidelblog.Net/ (blog), November 20, 2012. https://heidelblog.net/2012/11/was-calvin-a-homosexual-convict/. [ccxliv] Cottret, 225. [ccxlv] Parker, 105. [ccxlvi] Ibid., 106. [ccxlvii] So Cottret, 206. [ccxlviii] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1536 Edition (trans. Ford Lewis Battles; Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company; The H. H. Meeter Center for Calvin Studies, 1995), 61. [ccxlix] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1536 Edition (trans. Ford Lewis Battles; Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company; The H. H. Meeter Center for Calvin Studies, 1995), 62. [ccl] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion: 1541 French Edition (trans. Elsie Anne McKee; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009), 254. [ccli] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (ed. John T. McNeill; trans. Ford Lewis Battles; vol. 1; The Library of Christian Classics; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 1217. [cclii] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (trans. by Henry Beveridge, ed. Robert J. Dunzweiler; Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 1997). [ccliii] Theodore. Beza, L’histoire de la vie et mort de Calvin (1565), Opera Calvini 21, 39. Quoted in Bernard Cottret, Calvin, 207-208. [ccliv] Parker, 105. [cclv] Gordon, Calvin, 43. [cclvi] See Masten, “Bound for German,” 18. [cclvii] Echeverría, Francisco Javier Benjamín González. The Discovery of Lesser Circulation and Michael ServetusTs Galenism.s In 43th Congress of the International Society for the History of Medicine, Programme Book, Padua-Albano Terme (Italy) 12-16 September 2012, 2012. https://www.academia.edu/36341621/The_discovery_of_Lesser_Circulation_and_Michael_Servetuss_Galenism. [cclviii] Metaxas, Eric. Bonhoeffer : Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy : A Righteous Gentile vs. the Third Reich. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010. [cclxi] Lothar Machtan, The Hidden Hitler (trans. by John Brown; New York, NY: Basic Books), 2001. [cclxii] Stone, Charles. “What If Hitler Was Gay?” Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 9, no. 3 (June 5, 2002): 34.