The Perils of Enculturation in India

/“The Howrah Bridge” remains the quintessential symbol of the Indian state of West Bengal. The mighty cantilever structure that has no nuts and bolts and was constructed by riveting metal shafts and handles a daily traffic of 100,000 vehicles and possibly more than 150,000 pedestrians was one of the British Raj’s last construction projects in Bengal. The bridge survived the Second World War when the Japanese bombed Calcutta from 1942 to 1944 due largely to the swift deployment of balloons attached to the ground by several steel cables by the British. The planes would get stuck in the cables and crash. The Howrah Bridge connects the twin cities of Howrah (the place of my birth) and Kolkata and is erected over the Hooghly River, a distributary of the Ganges which winds its way into the Bay of Bengal. Like most rivers in India, the Hooghly is venerated and considered sacred by the Hindus especially since it is part of the Ganges which is considered the holiest of rivers in India. The Bengal or the Ganges river delta is the largest river delta in the world. What is extremely fascinating is that the Hooghly River and the settlements around it gave birth to the “Bengali Christian” phenomenon and was one of the hotbeds of missionary activity in Bengal.

With a length of 500 kilometres and lacking natural depth, it is unlikely to be named among the great rivers of the world today but there was a time when the Hooghly was renowned not only in Bengal and India but also across the world. Robert Ivermee in his book Hooghly – The Global History of a River says, “There was a time, however, when the Hooghly was a waterway of truly global significance, attracting merchants, missionaries, statesmen, soldiers, labourers, and others from Asia, Europe and elsewhere…Its tributaries and distributaries afforded access to deltaic Bengal, the Gangetic plain, and the Mughal heartland of Hindustan, linking northern and eastern India with territories across the Indian Ocean and beyond.” From the sixteenth century onwards, several foreign parties were drawn to the river including the likes of the Portuguese, French, Mughal, Danish and British.

In the autumn of 1578, a Portuguese trader by the name of Pedro Tavares completed a voyage to the bank of the Hooghly. Tavares was the latest in a succession of Portuguese to visit the Bay of Bengal. Ivermee writes, “Tavares’ aim was to unload a vessel’s worth of produce on the markets of the Bengal delta, wait four months for the monsoon winds to change, and return to Portuguese settlements on the western coast of India on a ship laden with merchandise further east.” However, things didn’t go exactly according to his plan. In the imperial capital of Fatehpur Sikri, about a thousand miles to the north-west, word of the activities of the Portuguese reached the ears of Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, Emperor of Hindustan, who expressed his desire to meet these strange foreign guests. Tavares resided at Fatehpur Sikri for a year. The frequency of his meetings with Akbar is unclear but it seems that Akbar was disappointed that the Portuguese was unqualified to explain and debate with him the finer points of Christian theology, a task for which a succession of European priests including several Jesuits were later summoned. Tavares, however seems to have charmed the Emperor and at their final audience, Akbar bestowed on him lavish gifts and the permission to found a Portuguese settlement in Bengal. The city of Hooghly was thus born.

The Portuguese had already established settlements in Chittagong (present day Bangladesh) which was a thriving trading post of the Portuguese Empire in the East. Now with the addition of Hooghly, Portuguese traders began populating the land, arriving with their wives and children from Chittagong or intermarrying with the local population. Tavares had also been granted permission to construct churches and monasteries and the right to propagate and practice Christianity. As in many parts of India, the first missionaries to arrive in Bengal were Jesuits. At Hooghly however, the primary religious order was not The Society of Jesus but the Augustinians. Hooghly’s founding led the viceroy of Goa to determine that Bengal would be a focus of Augustinian missionary endeavours, and with the dispatching of the first batch of priests, the Bandel Church came to be constructed in 1599. The first church was burnt down during the sacking of Hooghly by the Moors in 1632. A newer church constructed by Gomez de Soto was built over the ruins in 1660. On November 25, 1988, Pope St. John Paul II declared the sanctuary a minor basilica.

Missionary activity in Bengal continued unabated and one of the milestones in this regard was reached when Baptist minister, translator, social reformer and cultural anthropologist William Carey translated the Bible into Bengali in 1809. Another high point came during the Bengal Renaissance to which I have alluded to in “Bollywood’s Evolution” (CW February 2022) when many upper-class Bengalis, enamoured by the ideals of Christianity were baptized into the faith. One of the most prominent Bengali Christians of this age was the poet Michael Madhusudan Dutta. Madhusudan was deeply influenced by his teacher at Hindu College in Calcutta, who inspired in Dutta a love of English poetry, particularly Byron. He embraced Christianity in 1843 and did not take the name “Michael” until his marriage in 1848. He described the day of his conversion in his poetry as:

Long sunk in superstition’s night,

By Sin and Satan driven,

I saw not, cared not for the light

That leads the blind to Heaven.

But now, at length thy grace, O Lord!

Birds all around me shine;

I drink thy sweet, thy precious word,

I kneel before thy shrine!

Bengal during the late 18th century was a hotbed of intellectual activity ranging from artistic, social, cultural and theological movements. In 1828, Raja Ram Mohan Roy established the Brahmo Samaj, which kept Hindu ideals but denied idolatry. This resulted in a backlash within orthodox Hindu society. At around the same time, Indo-Portuguese poet Henry Louis Vivian Derozio founded the Young Bengal Association. Derozio was a poet and was greatly enamoured of the poetry of Byron, John Keats and Percy Shelley and his Young Bengal movement was an attempt to discuss ideas freely with a liberal bent of mind and also to reform society and free it from its orthodox chains. Unfortunately, Derozio died of cholera which at that time was a common killer in Bengal and the movement ran out of steam. One of its members however, apparently disappointed by the failure of Derozio, converted to Christianity in search for the answers to the troubles that plagued the Hindu society. Unlike Roy, whose Brahmo Samaj was conspicuously influenced by Christian teachings and yet he refused to turn fully to Christianity, Krishna Mohan Banerjee got himself baptized in 1832. Banerjee was a Derozian but after the poet’s death in 1831, he was impacted by Scottish missionary Alexander Duff who was his teacher at Hindu College. Banerjee was one of the earliest Bengali Christians who attempted what is called apologetics. His Hindu background and knowledge of the Hindu texts led him to publish two seminal works, Dialogues on the Hindu Philosophy and The Relation Between Christianity and Hinduism. The former book is written in the form of a dialogue between a Christian and a Hindu who are represented as two characters. Since this article is not about Hindu philosophy exclusively, I will refrain from getting into details but to just give an idea of what it contains, here is an excerpt. In this conversation the two characters, Satyakama (the Christian) and Agamika (the Hindu) are talking about The Holy Trinity. Here’s how the talk unfolds.

Agamika. – But I am told that the Christian religion which you are now advocating speaks of a plurality of gods, three gods.

Satyakama. – Not three gods, nor a plurality of gods, but a plurality of persons in the unity of the Godhead. This doctrine you can find no great difficulty in acknowledging, (1) because it is inculcated in the Bible which, as we have seen before, is attested by miracles and prophecies, and (2) because the Brahminical sastras themselves bear some confirmatory testimony to its truth.

Agamika. – How?

Satyakama. – The Brahminical sastras speak of a triad of divinities, Brahma, Vishnu, and S’iva. They speak of it, as one form and three gods. They tell us that they are mystically united in One Supreme Being. But the doctrine appears incongruous, and quite out of place in their system. The gods are frequently represented, not as different personal manifestations of the same Godhead ought to be, but as impure characters and antagonistic gods, wrangling and fighting with one another. S’iva fights and punishes Brahma, and Vishnu humbles S’iva. The votaries of Vishnu anathematize those of S’iva’, and the votaries of S’iva anathematize those of Vishnu. And all three are, again, pronounced to be transient and perishable. The doctrine represents an idea which is quite foreign to the Brahminical system, and we can only unravel the mystery by supposing it to be a relic of some primitive revelation, of which a distorted tradition had probably reached our ancestors.

Agamika. – These appear to be strange and novel views of things, and yet I certainly cannot gainsay them. Well is there any other point on which you can collect evidence from our sastras in behalf of Christianity.

Satyakama. – The doctrine of Christ’s incarnation for the redemption of the world, involved in the primitive revelation of a future Saviour, receives some confirmation from detached expressions in several portions of the Brahminical sastras. The idea propounded in the Bhagavad-gita and other works that Vishnu descends in human form for the relief of the world, whenever it is oppressed with sin and wickedness, is ill in keeping with the acts attributed to his alleged incarnations, of which Krishna is declared to have been the fullest and most conspicuous. I need not offend your ears by a description of his character. You will admit that from such a character it would be preposterous to expect any relief from sin. The idea was apparently derived by tradition from the primitive revelation of a future Saviour, and it was eagerly entertained owing to the necessities of sinful human nature, incapable of helping itself, and panting for reconciliation with God.

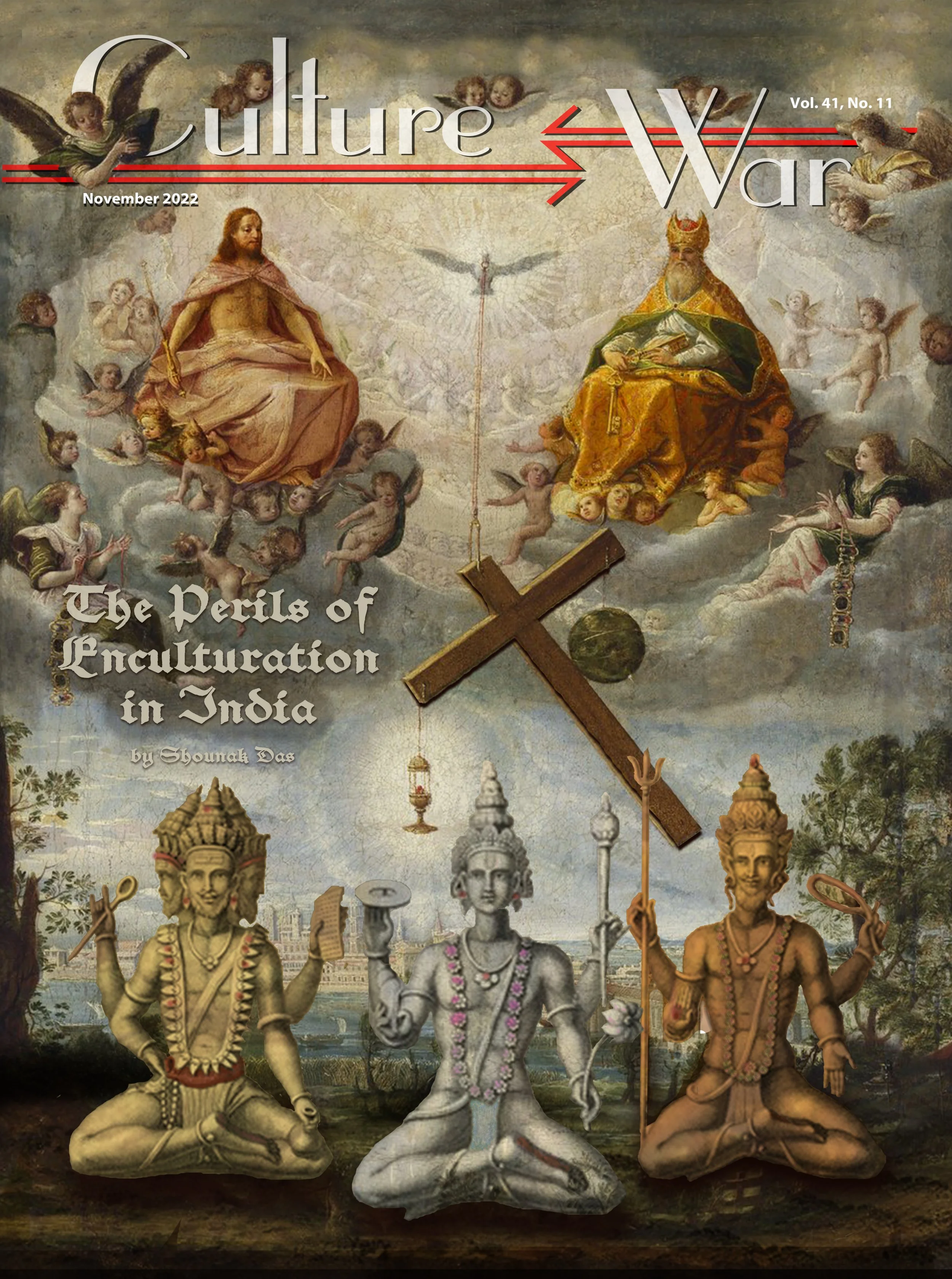

Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva

The above point which the character Satyakama makes about the present Brahminical system being a relic of some primitive revelation implying that the original message had been something else finds echo in the work of German-Austrian Catholic priest, linguist and ethnologist, Wilhelm Schmidt whose book The Origin of the Idea of God talks about all primitive cultures starting monotheistic and then probably due to moral corruption, devolving into polytheism. Agamika goes on to ask Satyakama about the ultimate goal or end of Christianity in the following dialogue.

Agamika. – But what is the great duty and what the chief end inculcated in the Christian religion ?…

[…] This is just an excerpt from the November 2022 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

(Endnotes Available by Request)