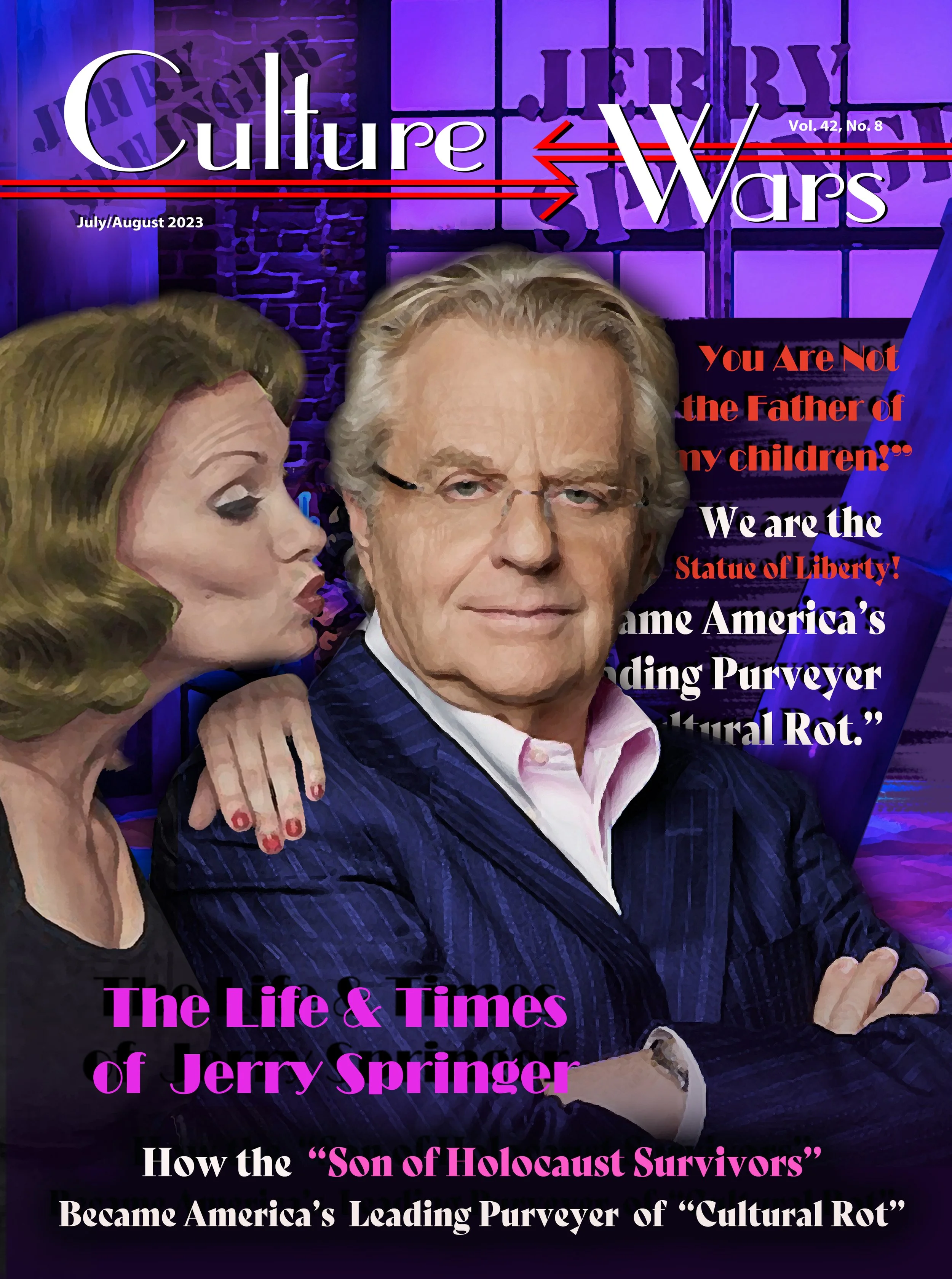

The Life and Times of Jerry Springer

/How the “Son of Holocaust Survivors”

Became America’s Leading Purveyor of “Cultural Rot”

““Charity thinketh no evil.””

EPILOGUE AS PROLOGUE

On the afternoon of Tuesday, April 30, 1974 Cincinnati’s most popular and divisive politician held an impromptu press conference announcing his departure from city council and civic life. One day earlier the local politico tacked a letter of resignation on his office door at city hall. His colleagues and the broader public were bewildered at the abrupt move, especially since the electorate’s enthusiastic reception of this ambitious young firebrand guaranteed his ascent to Cincinnati’s mayoral office later that year.

“A well-known Cincinnati political figure is currently the subject of a VICE investigation that is underway in both Ohio and Kentucky,” Cincinnati Enquirer political opinion editor Frank Weikel reported in the paper the previous day. “Word is that in the Kentucky investigation the figure and his attorney have already had ‘an interview’ with federal investigators and a federal prosecutor. In Cincinnati,” Weikel continued,

“authorities have not talked to him about association with a prostitution operation, but I have learned that several prostitutes have been interviewed and all tell stories that link him to a health club operation. LOOK FOR THIS STORY TO BREAK INTO THE HEADLINES IN THE NEAR FUTURE.”[i]

In the months leading up to the presser everything seemed to be going well for the 30-year old New York City transplant. He had a lovely new wife, the apparent fulfillment of a calling, and a charisma that might take him to the highest echelons of U.S. political power. Yet the careless pursuit of his carnal passions—and more to the point, the impending exposure of those misdeeds—would forever nullify the life in politics he so deeply sought. “It was a bitter twist,” one local writer noted, “an epilogue to what was, instead of a prologue to what might have been.”[ii]

Days earlier the young policymaker heard about the prostitution bust on the local newscast. “I remember being startled” at the news. “I had been to this club. I had been a customer.” He then began receiving calls at City Hall from unidentified parties. “‘We know you were there,’” the voices on the other end said. “‘You’ll be hearing from us.’”[iii]

Fearing the event would soon become public, the councilman owned up to the indiscretions before his tearful new wife of six months and other close associates. Then the telephone rang. “‘I hear you are resigning,’” a local reporter queried.[iv] As all of this quickly transpired the short-lived political career of Gerald Norman “Jerry” Springer was crashing around him. A “red-eyed and shaken” Springer faced reporters, and with a quivering voice revealed how “on two occasions I have been a customer of a ‘health club’ in Northern Kentucky and engaged in activities which, at least to me, are questionable. These actions have weighed heavily on my conscience,” he continued, “and early last week I contacted the FBI and voluntarily answered all inquiries of what I had done, and of what I had knowledge. I am continuing to cooperate in that investigation in any way I can.”[v]

In what might have been a scenario prompting the fur to fly a few decades later on his infamous television program, the young newlywed lawmaker was embroiled in a shocking sex scandal.

In December and January of the previous winter Springer paid for two separate “‘acts of prostitution’” occurring at the Motor Inn in Ft. Wright, Kentucky with two personal checks totaling $75. Springer had at the time been married for six months to Margaret (Micki) Velten of Cynthia Kentucky, a University of Cincinnati elementary education student. “By the end of April, the checks resurfaced; or, as Springer says, a crescively guilty conscience compelled him to act. Whatever, he was cancelled out of public office.”[vi] Springer’s infidelity transpired in the Northern Kentucky metro area across the Ohio River known for its vice, and thus popularly referred to as “Cincinnati’s playground.” It was the same region where, twelve years earlier, Springer’s political champion, then-US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, ousted “an entrenched Jewish syndicate and Italian mafia organized crime element” that included infamous Jewish mobster Moe Dalitz.[vii]

The young councilman’s public explanation for owning up to the transgression was that, unlike other politicians, he was truthful and thus felt an inner compulsion to resign. “‘How are we different from the traditional politician?’” Springer asked. “‘What was it that we thought always separated us from others? Honesty. It was that simple … Sometimes you have to do it because it’s the right thing to do. I have few regrets.”[viii]

"My Passion Was Politics"

Jerry Springer was born in London, England on February 13, 1944 during the “baby blitz,” reportedly in the city’s subway system that served as an impromptu air raid shelter. Springer’s parents, Richard and Margot, were married in March 1933 “in a small, secret ceremony held in a private home in Berlin” because, according to Jerry, “the synagogues were all closed.” In November 1938 “during the height of an anti-Semitic terror campaign” popularly known as Kristallnacht, Springer’s father Richard “unwittingly escaped capture when brownshirt vigilantes searched his home. He was not there.”[i] The experience prompted Jerry’s parents to flee the continent. In their haste they left behind both of their mothers and Richard’s brother Kurt, the seeming fate of which would become not only part of Jerry’s ethnic identity, but also a central feature of his political and entertainment brand.

Jerry Springer’s sole sibling (Evelyn) and parents emigrated to the U.S. in 1949. As Springer often remarks, “I left England at age five when I found out I couldn’t be king.” And therein lies a more revealing truth about Springer’s character than of Bob Hope’s, from whose repertoire he borrowed. With the assistance of a New York-based Jewish refugee foundation the family settled in a tightly-knit Jewish neighborhood in Queens, New York, where Springer’s aunt resided. Richard Springer made stuffed animals and peddled them on street corners, with Jerry often in tow. Margot worked as a bank clerk. Jerry’s mother laid down firm rules governing the household. ”It was always work before play,” she recalls. “‘I guess it’s the German in us.’” In high school Springer was a popular and “precocious classroom clown.” At the same time “teachers complained to his parents that ‘with his ability he should be doing better.’” Upon graduation his parents insisted that he leave home to attend university. Jerry chose Tulane and its exotic New Orleans backdrop over UCLA, Wisconsin and Cornell, where he also gained admittance.[ii]

Like many European-Jewish immigrants the Springers were politically and culturally liberal—identifying this impulse with their European background where, Jerry emphasizes, “politics wasn’t just a hobby. Politics had wiped out our family.’” “‘My parents were [former Illinois Governor, 1956 Presidential Candidate, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations] Adlai Stevenson Democrats,’” Springer explains. “‘Whatever heroes we had even in the music world—Pete Seeger, Joan Baez—always seemed to be in the avant garde, caught up in that whole civil rights milieu.’”

At Tulane Springer majored in political science, became head of his fraternity, “and for the first time I had a social life. I had girlfriends,” he reminisces. “I was falling in love every night.” Already ethnically imbued with the Jewish revolutionary spirit, the London-via-New York wayfarer participated in the black civil rights movement well underway throughout the South, involved himself in the project to integrate New Orleans’ high school in 1961, went on black voter registration drives in Mississippi, and overall “became obsessed with the whole civil rights movement. I really do believe my parents ingrained in me an inherent sense of justice,” Springer declares. “I don’t think you can be a child of the Holocaust and not have that hot button when it comes to any issue of discrimination. I never even had to think about it. It was and remains in my blood.”[iii]

Jerry’s southern junket fortified this radical fire, causing him to more seriously ponder a career in politics. With civil rights as a gateway Jerry was eventually drawn toward the anti-Vietnam War movement. Despite an extroverted nature and frequently vying to be the center of attention, Narcissus-like Jerry failed to foster any enduring collegial or romantic relationships as an undergrad. “‘Since I left [Tulane] in ’65 I have never heard from anyone I knew there,’” he wistfully admits a decade later. “‘It’s really strange. But, oh, was New Orleans great!’”

In 1965 Jerry enrolled in Northwestern University’s law school. “I don’t even remember making a decision about going to law school,” he remarks in his blithe autobiography. “I guess it was just assumed—once it was figured out I didn’t have the stomach to be a doctor.”[iv] Two decades earlier as a still-aspiring politician, however, he explains the fact that Adlai Stevenson and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg were both Northwestern law grads gave Evanston a liberal veneer.[v]

The following year Springer interviewed for an internship at Cincinnati’s Frost and Jacobs law firm—among the city’s most prestigious. As Jerry recalls, he didn’t really fit in at the conservative organization. “My guess is they’d never had a Democrat, nor do I believe they’d ever had a Jew working there,” he recalls.[vi] “They certainly never had a liberal, and here I was a war protester. I would say things like … ‘We’ve got to get out of the war; it’s horrible.’ I mean, I was this pinko lefty, a total liberal.’” To Jerry’s amazement the firm brought him on to clerk over the 1967 summer break.

While attending a Democratic Party soirée in early 1968 a University of Chicago professor introduced Springer to Senator Robert Kennedy, which further intensified Jerry’s desire to pursue a political career. For three months the law apprentice campaigned throughout the Midwest in support of Kennedy’s Democratic presidential nomination, all the while envisioning himself fighting corruption one day alongside RFK in Washington. That dream was cut short with Kennedy’s assassination in June 1968. Despite the setback Springer yearned to bring his reformist ideas and persona into public office. “My passion was politics: civil rights, the antiwar movement,” he admits. “I guess I just saw law as a way to make a living.”[vii]

After receiving his JD from Northwestern Jerry earned a junior position at Frost and Jacobs. Entry standing at such a well-connected firm was a dream job for most fledgling lawyers. Yet Jerry left in less than six months and “picked the most conservative district in Ohio” to run on an antiwar platform in the Democratic primary for U.S. Congress. On the campaign trail Springer argued that lowering the voting age from 21 to 19 was justified given that if young men were old enough to fight in an “undeclared foreign war” they were surely mature enough to vote. The campaign’s promotional materials touted Springer as being “on leave from Frost and Jacobs,” when he had in fact resigned from the firm.[viii] Shortly after his campaign got underway he was drafted into the U.S. Army and spent several weeks in basic training until he was summoned to Washington D.C. to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee on lowering the minimum voting age.

Springer won the Democratic Party Congressional nomination, defeating his opponent, Vernon Bible. “It wasn’t easy to run against a man named ‘Bible,’ particularly in this conservative district” he later teased. Still, Jerry could not prevail against the “very Republican, very conservative” incumbent and former Cincinnati Mayor Donald Clancy. Despite the loss Jerry’s competitive campaigning was enough to win favorable attention from established politicos, and his bid for a seat on Cincinnati’s city council met with overwhelming success.[ix]

A sizable portion of the area’s electorate were attracted to the energetic and partisan liberal from back east—indeed the unpredictable toastmaster who might either rise and discuss any number of then-current political concerns, or grab his acoustic guitar and belt out a folk tune like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” or “This Land is Your Land,” as he’d done in the halcyon days of civil rights demonstrations and Tulane beer blasts.[x] “I don’t know—when you look at it on paper,” Springer told a local reporter following the election, “it really doesn’t make sense, does it? I guess all you can say is I’ve touched a nerve here.” [xi] …

[…] This is just an excerpt from the July-Aug 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

(Endnotes Available by Request)

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

The Life and Times of Jerry Springer by Dr. James F. Tracy

The Hidden Grammar of the Dodger–Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Controversy by E. Michael Jones

Features

Why Hawthorne was Melancholy:

The “Lost Clew” Explained by E. Michael Jones

Reviews

The Beatific Vision by Lise Anglin

Endnotes

[i] Cameron Knight, Jerry Springer in the News: How the Prostitution Scandal Broke,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 2, 2017, https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2017/06/02/jerry-springer-news-how-prostitution-scandal-broke/366721001/; Frank Weikel, Cincinnati Politico Reported Under Two-State Vice Probe,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 29, 1974.

[ii] Tom Hayes, “Jerry Springer: The Cincinnati Kid,” Clifton Magazine, Winter 1974/75, p. 8+, https://digital.libraries.uc.edu/exhibits/arb/cliftonmag/documents/springer.pdf

[iii] Jerry Springer and Laura Morton, Ringmaster (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), pp. 59-61.

[iv] Aileen Joyce, Jerry Springer: Unauthorized Biography (New York: Zebra Books/Kensington Publishing Corp. 1998), p. 44.

[v] “Activity Questionable, Says Springer,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 1974, A1; “Jerry Springer Admits Paying for Sex, Resigns from Cincinnati City Council in 1974,” WCPO 9, YouTube, April 28, 2016.

[vi] Hayes.

[vii] Richard Challis, “Northern Kentucky, The State’s Stepchild: Origins and Effects of Organized Crime” (Highland Heights, KY: Northern Kentucky University Digital Repository, n.d.) https://dspace.nku.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/1ba72c87-0a1c-4db4-b49b-76e8e832dd6c/content

[viii] Hayes.

[ix] Hayes.

[x] Joyce, pp. 21-25; Hayes.

[xi] Springer and Morton, p. 40. Emphases retained.

[xii] Ibid., p. 45.

[xiii] Hayes.

[xiv] The firm’s prominent co-founder, Carl Jacobs, served as the former Vice Mayor of Cincinnati. Christopher S. Habel, “Frost Brown Todd Celebrates 100-Year Anniversary,” frostbrowntodd.com, October 25, 2019, https://frostbrowntodd.com/frost-brown-todd-celebrates-100-year-anniversary/

[xv] Springer and Morton, pp. 45-47.

[xvi] Hayes.

[xvii] Springer and Morton, pp. 51, 54.

[xviii] Joyce, p. 31; John Kiesewetter, “Jerry Springer Celebrated with Songs and Lots of Laughs,” 91.7 WXVU News, June 9, 2023, https://www.wvxu.org/media/2023-06-09/jerry-springer-memorial-celebration-wlwt-tv-tvkiese

[xix] Joyce, pp. 31-32.

[xx] “Jerry Springer Says His Show is Stupid,” Letterman, YouTube, April 24, 1998.

[xxi] Joyce., p. 36.

[xxii] Biography: Jerry Springer.

[xxiii] Joyce, pp. 35-37, 197.

[xxiv] Ibid., p. 32.

[xxv] Hayes.

[xxvi] Joyce, p. 31.

[xxvii] “Cincinnati,” Jewish Virtual Library, n.d., https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/cincinnati ; Tim Burke, “The Cox Machine,” Cincinnati History, December 3, 2019, https://www.cincinnatihistory.org/post/the-cox-machine; Stephen Birmingham, “Our Crowd”: The Great Jewish Families of New York (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers Inc., 1967/2004), pp. 62-63.

[xxviii] Springer and Morton, pp. 14, 15.

[xxix] Joyce, pp. 32-33.

[xxx] Will Herberg, Protestant, Catholic, Jew: An Essay in American Religious Sociology (Garden City NY: Anchor Books/Doubleday & Co., 1960/1955), pp. 173-174.

[xxxi] Roth, p. 236.

[xxxii] Hayes.

[xxxiii] Springer and Morton, pp. 95-96.

[xxxiv] Roth, pp. 232-233. Cited in E. Michael Jones, The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History (South Bend IN: Fidelity Press, 2012), p. 946.

[xxxv] Jones, pp. 946-947.

[xxxvi] Joyce, p. 34.

[xxxvii] Joyce, p. 37.

[xxxviii] Hayes.

[xxxix] Joyce, p. 44.

[xl] “Carl Lindner Jr., 92, Major Non-Jewish Donor to Jewish Federation, Israel Bonds for 50 Years,” The Jewish News of Northern California, November 4, 2011, https://jweekly.com/2011/11/04/carl-lindner-jr-92-major-non-jewish-donor-to-jewish-federation-israel-bond/

[xli] Joyce, pp. 45, 42.

[xlii] Ibid., pp. 49-50.

[xliii] Hayes.

[xliv] In 2008 Springer conducted genealogical research, appeared on the BBC series, Who Do You Think You Are, claiming that his maternal grandmother “was dispatched in a cattle train to Chelmno extermination camp, where she was among the first to be gassed to death.” His paternal grandmother “was deported to Theresienstadt, a Jewish ghetto near Prague.” “Jerry Springer, The Holocaust and My Family,” The Independent, August 23, 2008, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/jerry-springer-the-holocaust-and-my-family-905317.html

[xlv] Hayes.

[xlvi] Joyce, p. 58.

[xlvii] Springer and Morton, p. 62-63.

[xlviii] “Jerry Springer for Governor: A 1980 Campaign Ad,” philbot, YouTube, September 20, 2006.

[xlix] Joyce, pp. 62-63; Biography: Jerry Springer.

[l] David Plotz, “Jerry Springer: Once the talk show host was the mayor of Cincinnati. Now he’s the mayor of Sodom,” Slate, March 22, 1998. https://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/assessment/1998/03/jerry_springer.html

[li] Joyce, p. 56; Springer and Morton, p. 70.

[lii] Springer and Morton, pp. 70-71.

[liii] Springer and Morton, pp. 72-73.

[liv] Joyce, pp. 72-73.

[lv] “Jerry Springer: ‘I Don’t Know Why People Want To Come On The Show’,” TODAY, YouTube, February 15, 2017.

[lvi] Springer and Morton, pp. 253-258.

[lvii] Joyce, p. 94.

[lviii] Springer and Morton, pp. 93-94.

[lix] Joyce, p. 95.

[lx] “Jerry Springer,” Biography, 1998, JPmcFly1985 Retro Videos, YouTube, May 17, 2020.

[lxi] “Jerry Springer on ‘Larry King Now’,” Larry King, Youtube, February 10, 2014.

[lxii] “A Curse Haunts Firms that Acquire Universal,” Forbes, June 13, 2002, https://www.forbes.com/2002/06/13/0613universal.html?sh=cb2b2a719c16

[lxiii] Joyce, p. 95.

[lxiv] “Jerry Springer: ‘I Don’t Know Why People Want To Come On The Show’.”

[lxv] “Jerry Springer,” Biography.

[lxvi] Springer, p. 144.

[lxvii] Joyce, p. 96.

[lxviii] Allison J. Waldman, “‘Springer’ Hits 3,000: American Pie,” TV Week, May 8, 2006.

[lxix] Springer and Morton, p. 133.

[lxx] Joyce, pp. 109-110. In November 1996 Schmitz was convicted of second-degree murder and given a 25-50 year prison sentence. Joyce, p. 119.

[lxxi] Joyce, p. 111.

[lxxii] Waldman; Joyce.

[lxxiii] Waldman; Springer and Morton, p. 218.

[lxxiv] Joyce, p. 112.

[lxxv] Ibid., p. 115.

[lxxvi] Springer and Morton, pp. 260-264.

[lxxvii] Joyce, p. 120.

[lxxviii] Joyce, pp. 96-97; Jerry Springer: Too Hot For TV, IMBD.com, n.d., https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0163021/?ref_=tt_mv_close

[lxxix] Waldman; Springer and Morton, pp. 171-172.

[lxxx] Waldman.

[lxxxi] “Steve Wilkos: Crazy Stories from Jerry Springer Days,” Hollywood Raw, YouTube, June 15, 2022.

[lxxxii] Waldman.

[lxxxiii] Jim Benson, “Springer Stays on Board,” Broadcasting & Cable, January 16, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20080601045359/http://www.broadcastingcable.com/article/CA6299596.html

[lxxxiv] Springer and Morton, pp. 140-141.

[lxxxv] “Jerry Springer,” Biography.

[lxxxvi] “Jerry Springer on ‘Larry King Now’.”

[lxxxvii] “Jerry Springer,” Biography.

[lxxxviii] Joyce, pp. 129-130.

[lxxxix] Biography: Jerry Springer.

[xc] Joyce, p. 128.

[xci] “Jerry Springer on ‘Larry King Now’.”

[xcii] “Full Interview: Fred Borek III, Producer of Jerry Springer Show Shares His Favorite Moments,” Will & Woody, April 28, 2023. https://www.radio-australia.org/podcasts/will-woody

[xciii] “The Jerry Springer Producers Who Caused the Chaos.”

[xciv] “The Jerry Springer Producers Who Caused the Chaos,” Dark Side of the 90’s, Vice TV, YouTube, September 29, 2022.

[xcv] Springer and Morton, pp. 193, 196.

[xcvi] “Full Interview: Fred Borek III, Producer of Jerry Springer Show.”

[xcvii] “The Jerry Springer Producers Who Caused the Chaos,” Dark Side of the 90’s, Vice TV, YouTube, September 29, 2022.

[xcviii] A 2014 study reveals that over 75% of men and women between 18 and 30 years of age report watching pornography at least once per month. In a related 2016 study, over 95% of young adults “are either encouraging, accepting, or neutral when they talk about porn with their friends.” Porn Stats: 250+ Facts, Quotes and Statistics About Pornography Use, Covenant Eyes (Owosso MI: 2018) http://www.covenanteyes.com/pornstats/

[xcix] As one porn vendor puts it, “‘Amateurs come across better on screen. Our customers feel that. Especially by women you can see it. They feel strong pain.’” Katharine Sarikakis and Zeenia Shaukat, “The global structures and cultures of pornography: The global brothel,” in Feminist Interventions in International Communications: Minding the Gap, ed. Katharine Sarikakis and Leslie Regan Shade (Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 106-116. Quoted in Covenant Eyes, p. 6.

[c] “The Jerry Springer Producers Who Caused the Chaos.”

[ci] E. Michael Jones, Libido Dominandi: Sexual Liberation and Political Control (Fidelity Press, 2018/2000), p. 331.

[cii] Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[ciii] “Going All the Way: Public Opinion and Premarital Sex,” Roper Center For Public Opinion Research, July 7, 2017, https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/blog/going-all-way-public-opinion-and-premarital-sex

[civ] Frank Newport, “Continuing Change on US Views on Sex and Marriage,” Gallup, June 18, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/351326/continuing-change-views-sex-marriage.aspx

[cv] Marquis de Sade, Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom & Other Writings, complied and translated by Richard Seaver and Austryn Wainhouse (New York: Grove Press, 1965), p. 315. Quoted in Jones, Libido Dominandi, p. 6.

[cvi] “Jerry Springer: ‘We Had a Holocaust Before Anyone Had a Television Set,’” Guardian, April 6, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/apr/06/jerry-springer-tabloid-holocaust-tv

[cvii] See Bernard Nathanson, The Abortion Papers: Inside the Abortion Mentality (New York: Frederick Fell Publishers Inc., 1983).

[cviii] Betsy Reed, “F*** You, Says BBC, As 50,000 Rage at Spr*ng*r,” Guardian, January 9, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2005/jan/09/broadcasting.religion

[cix] “Say No to ‘Jerry Springer’ Opera in Carnegie Hall,” TFP.org, January 29, 2008.

[cx] Reed.

[cxi] Amy Bingham, Talk Show Host Jerry Springer is a ‘Die Hard’ Obama Supporter,” ABC News, July 19, 2012, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/OTUS/jerry-springer-obama-exceptional/story?id=16812750; “Jerry Springer: ‘We Had a Holocaust’”.