“Our Humor Expresses Our Concerns” Norman Lear and the Politics of Jewish Revolutionary Laughter

/“…they drag into the synagogue the whole theater, actors, and all. For there is no difference between the theater and the synagogue.”

– St. Chrysostom¹

“Inviting people to laugh with you while you are laughing at yourself is a good thing to do. You may be the fool but you’re the fool in charge.”

– Carl Reiner²

Norman Lear

“A thousand people can cross themselves,” celebrated television producer Norman Lear once remarked, “and it wouldn’t be as spiritual to me as watching people laughing together, as one.”3 To what end does such laughter serve? Mr. Lear will turn 101 on July 27, 2023, and his influence on the typical American’s political and cultural imagination at a crucial time in the twentieth century culture wars cannot be overestimated. Lear’s work “introduced the country to,” as one observer puts it “the ‘relevance programming’ form of situation comedy. This type of writing was didactic, dramatic, and most important, relevant—at least for those doing the actual writing.”4

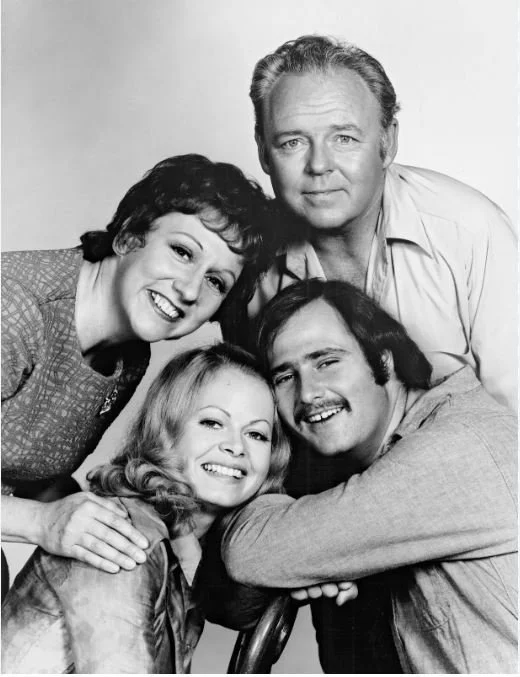

Along those lines the noted writer was among the first major TV producers to persuasively introduce the notion of “bigotry” into the national psyche alongside a range of other previously taboo topics. Lear’s groundbreaking situation comedy All in the Family (AITF) was his interpretation of a Christian American family not unlike the one I grew up in. As an agnostic Jew with revolutionary ideals, it was a milieu that he and his kindred Jewish writers were at once most distanced from and hostile toward.

I was five years old when the widely celebrated show debuted. After I was put to bed with the explanation of how something on TV was going to be “too old” for me, I could hear my parents laughing uproariously as they watched the program together. Several years later I caught the re-runs broadcast weekday eves on New York City’s WNEW TV. I never thought about who produced the program, or it potentially being one of many forms of Judaization I would encounter throughout my life. To be sure, during the 1970s there were other notable and controversial sit coms produced by Jews, in particular the Mary Tyler Moore Show (James Brooks and Allan Burns) and M*A*S*H (Larry Gelbart), but neither proved as politically incendiary or overall influential as AITF.

My mother would on occasion remark that the show’s main character, Archie Bunker, “is just like your father.” “I am not like him,” my father countered. The taunt must have seemed cruel to my dad, because even though he never used poor grammar or uttered racial epithets, he was an academic underachiever whose father and brother were, in contrast, both accomplished physicians. And dad did share certain personal characteristics with Archie, the foremost being his visceral rejection of what was taking place in the country at that time.

All in the Family

The Jewish Norman Lear and my Irish Catholic father were both part of the “Greatest Generation.” They both served in the 15th Air Force during the Second World War. Both were stationed in Italy and were shot at by the Germans. Lear flew in a B-17 as a radio man and side-gunner; my father was a tail-gunner in a B-24. Both went on bombing runs targeting German army formations in Northern Italy and Austria.5 My father’s brother also graduated from University of Notre Dame a few years before Father Theodore Hesburgh began to steer the college in its secular decline. Hesburgh would one day launch Lear’s formal career in political activism.

The correspondences ended there. By the 1950s my father had settled near his hometown in western New York State to work for a small insurance company and raise a family. Lear launched his career in show business by falsely posing as a journalist to infiltrate Danny Thomas’ entourage and gain a foothold in comedy writing.6 Eventually a high-ranking television producer, his controversial work set off millions of culturally and politically-infused discussions among families and friends throughout the 1970s.

Like my father and Lear, AITF’s central character and patriarch Archie was a U.S. Air Force veteran7 whose sentiments came to exemplify millions of sullen American men that perceived the rise of the civil rights and feminist movements, the Vietnam War, and the rapidly crumbling morality of the country as abundant evidence the world they knew was being torn asunder, but they were powerless in putting their finger on the specific causes. To make matters worse, in our household the family’s Catholic spiritual tradition was upended through fundamental changes to its liturgy.

Archie’s trademark frustration, pessimism and ill-temperament were natural reactions to the spirit of rebellion running through seemingly every facet of normal life. This fundamental rejection of such change was at its root a denunciation of the Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and what it wrought throughout the West. Yet crucially, Lear suffused Archie’s representative anxiety with a matching chauvinism and ignorance, thereby deeming it blameworthy antagonism toward the “change” and “progress” he and his Jewish contemporaries effected while all the while maintaining everything was due to a sort of natural historical evolution.8

Jewish social scientists throughout the post-war period succeeded in pathologizing America’s Christian subconscious as a wellspring of “bigotry.”9 Lear and his team of writers likewise brought this distorted rendering of the American psyche to life in the Archie Bunker persona, a man whom the celebrated producer describes as “a fearful human being” who “was afraid of tomorrow. He was lamenting the passing of time,” Lear says of the Bunker pater, “because it’s always easier to stay with what is familiar and not move forward.”10 At the same time, to demonstrate how he and his cohort perceived bigotry lurking around every other corner (disguised in different “stripes and attitudes”) Lear sought to fashion Archie as a personable, even “lovable” character one might encounter in their everyday lives.11

As Lear crafted AITF he functioned not so much as a television writer as he did a secular Jewish activist. He confirmed this activist role both as a member of the “Malibu Mafia,” an unofficial group of wealthy Jewish men who donated to liberal political causes, and even more so when he founded People for the American Way a decade later. With that organization Lear fought against the Supreme Court’s potential rollback of legalized abortion and the separation of church and state established ten years earlier when prayer was removed from public education.

As AITF’s first season ensued President Nixon can be heard condemning the program in the Oval Office tapes. Invoking New York’s “Hard Hat Riot” of 1970 in which construction workers clashed with anti-war protesters, Nixon contended that Lear sought to “downgrade” Archie’s “hard hat” character “and make the square hard hat out to be bad.”12 Nixon’s analysis was correct. As Carrol O’Connor put it, “Lear was irritated by my calling the series a satire, but if it was not … Richard Nixon was right, and we were doing the persona of Archie Bunker an injustice.”13 Indeed, via AITF Lear set the groundwork for the now-widespread notion of “white supremacy” by cleverly placing the Jewish community’s long-held obsession over bigotry in tens of millions of American living rooms on a recurring basis.

Decadence Writ Large

In the 1950s the Jewish clique of “New York Intellectuals imposed their image of themselves – the lonely, alienated outsider – onto the culture,” E. Michael Jones observes. “The Jews imposed their image on American culture not by making Americans Jewish by religion, but Jewish by way of alienation.”14 Such was also the case with the fundamental values underlying behavior. Cultural historian Andrew Heinze notes how the well-known Jewish newspaper advice columnists, twin sisters Ann Landers (née Esther Pauline Lederer) and Abigail Van Buren (née Pauline Esther Phillips)

accurately represented the values of the American Jew of the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. They believed in God and Country, espoused liberal Judaism and liberal politics, frowned on public expressions of religious and racial intolerance but disliked traditionalist [i.e. Catholic] forms of Christianity, accepted sexual drives as good (i.e., not sinful), tolerated abortion, and, though not endorsing homosexuality, attacked homophobic intolerance.

Once the sexual revolution came to pass, however, the very decadence Landers and Van Buren embraced “began to sound conservative in the nation’s most cosmopolitan areas.”15 Thus by the early 1970s when “the majority of American Jews defined themselves as sexually deviant, pornography, along with homosexual rights, feminism, and New Age goddess worship become a natural expression of their worldview.” And since they dominated mass media and “Hollywood, they could make their worldview normative for the culture.”16

AITF was among numerous socio-cultural devices that sought to instill in middle America such Judaic sensibilities and propriety, and thereby further accelerate America’s overall Judaization. In AITF’s first season alone such daring topics as premarital sex, homosexuality, feminism, economic class disparity and housing integration resembled the historically analogous process by which pornography crept into neighborhood movie theatres as “art cinema.” Lear and his cohorts thereby pushed the boundaries of the topics deemed as morally and culturally acceptable social discourse in the typical American household.

Throughout AITF’s 12 television seasons, Archie is akin to the classic hubristic protagonist, destined to be relentlessly humiliated due to his trademark awkward embrace of tradition. Yet unlike the customary use of this literary device to illustrate a vital character flaw, Archie’s hubris serves as a vehicle for his “bigotry,” which is his true failing that in time will be reformed. When Archie was retired from prime time in the early 1980s he had himself become thoroughly Judaized. In 1981, for example, on a two-part episode of AITF’s successor program Archie Bunker’s Place, Archie and his then-late wife Edith’s Jewish stepdaughter celebrated American television’s first bat mitzvah.17…

[…] This is just an excerpt from the June 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!