Oppenheimer: Applied Jewish Science

/Oppenheimer

In his recent biopic Oppenheimer, Director Christopher Nolan goes out of his way to portray the Manhattan Project as a Jewish operation from start to finish. The Jewish issue come up early on in the film when Oppenheimer meets his eventual nemesis Lewis Strauss, who goes out of his way to say that his name is pronounced “Straws,” to signify his assimilation as not just an American but a Southerner as well. Oppenheimer responds by giving two different pronunciations of his name but adds “whatever way you say it, they know I’m Jewish.” Strauss responds by assuring Oppenheimer he’s Jewish too. In fact, he’s “president of Temple Emmanuel in Manhattan. “Straws” is just a southern pronunciation” of a name that would otherwise be an obviously Jewish name. Having established their common Jewish identity, Strauss welcomes Oppenheimer to the Institute for Advanced Studies and assures him, “I think you’ll be very happy here.”[i]

Roughly two minutes later in the film, Oppenheimer goes through the same ritual bonding with Isidor Isaac Rabi, another Jew who ends up working on the Manhattan Project:

Rabi: It’s a long way to Zürich, if you get any skinnier we’re gonna lose you between the seat cushions. I’m Robby.

Oppenheimer: Oppenheimer [introducing himself]

Rabi: I caught your lecture on molecules, caught some of it. For a couple of New York Jews, how do you know Dutch?

Oppenheimer: Well, I thought I better learn it when I get here this semester.

Rabi: You learn enough Dutch in 6 weeks to give a lecture on quantum mechanics?

The message here is that Jews are smart.

Oppenheimer: I had to challenge myself.

Rabi: Quantum physics wasn’t challenging enough, shpitz?

Oppenheimer: Shpitz?

Rabi: Show off.

Oppenheimer: Ha!

Rabi: Dutch in 6 weeks, but you don’t know Yiddish?

Oppenheimer: I don’t speak it so much my side of the park.

Oppenheimer here is referring to the antagonism between the German Jewish immigrants to the United States who came over during the first half of the 19th century and their less cultured counterparts from the shtetl who came over at the beginning of the 20th century. “Our Crowd” held the Ostjuden in contempt, but Jewish Science was on its way to healing that rift.

Rabi: Screw You. You homesick?

Oppenheimer: Oh, you know it.

Rabi: Ever get the feeling our kind isn’t entirely welcome here?

Oppenheimer: Physicists?

Rabi: That’s funny.

Oppenheimer: Not in the department.

Rabi: They’re all Jewish too. Eat. There’s a German you have to seek out.

Oppenheimer: Heisenberg?

Rabi: Right.

In other words, the Manhattan Project is a totally Jewish operation, which is held together by the German physicist Werner Heisenberg.

During a meeting in Oppenheimer’s classroom at Berkeley, General Groves begins discussion of Oppenheimer’s involvement with the atom bomb project by asking him: “So how would you proceed?”

Oppenheimer: You’re talking about turning theory into a practical weapon system faster than the Nazis.

Groves: Who have a 12-month head start.

Oppenheimer: 18

Groves: How can you possibly know that?

Oppenheimer: Our fast neutron research took six months, and the man they’ve undoubtedly put in charge would have made that leap instantly.

Groves: Who do you think they put in charge?

Oppenheimer: Werner Heisenberg. He has the most intuitive understanding of atomic structure I’ve ever seen.

Groves: You know his work?

Oppenheimer: I know him. . . . In a straight race the Germans win. We’ve got one hope…

Groves: Which is?

Oppenheimer: Anti Semitism.

Groves: What?

Oppenheimer: Hitler called quantum physics “Jewish Science,” said it right to Einstein’s face. Our one hope is that Hitler is so blinded by that that he’s denied Heisenberg proper resources because it’ll take vast resources, our nation’s best scientists working together. Right now, they’re scattered.

Groves: Which gives us compartmentalization.

Oppenheimer: All minds have to see the whole task to contribute efficiently. Poor security may cost us the race, efficiency will. The Germans know more than us anyway.

Groves: The Russians don’t.

This scene encapsulates the entire gamut of Nolan’s film even though it cannot be found in Kai Bird’s American Prometheus, which serves as the basis for the film. Nolan inserted it into the film because it introduces all of the fundamental elements which drive its plot.

First of all, Jewish scientists were the driving force behind the Manhattan Project. Without them, most notably Oppenheimer, the project would not have succeeded.

Secondly, the Jews who ran the project were beholden to Heisenberg as the man who came up with the theoretical basis for Quantum Mechanics. Jews like Oppenheimer and Raab could only fill in the gaps in the framework Heisenberg provided.

Thirdly, Heisenberg was working on the Nazi bomb project, but he was not constrained by Hitler’s understanding of what the Nazis called “Jewish science.” Heisenberg deliberately thwarted the successful completion of the Nazi bomb project because of the Christian formation of his conscience that took place while growing up a Protestant in Catholic Bavaria.

Fourthly, there is no evidence that Oppenheimer, who was always ambivalent about his Jewish identity, would have mentioned anti-Semitism to a goy like General Groves. By inserting this fictional dialogue into his film, Nolan is telling us that the Jews who worked on the Manhattan Project justified their participation in creating a weapon of mass destruction that was going to be deployed against civilians by making it part of the Holocaust Narrative.

Fifthly, by mentioning the Russians, Nolan is adverting to the fact that the Jews involved in the Manhattan Project had divided loyalties. They had to get security clearances from the American government to work on the Manhattan Project, but their natural inclination was to support the then current manifestation of the Jewish revolutionary spirit, which was Communism. Which is another way of saying that their first loyalty was to the Soviet Union. Their sense of urgency increased in 1943, when they felt that the Nazis were winning the war. The year 1943 marks the moment that top secret information about the development of the atomic bomb started passing from the Jews connected with Los Alamos to the Jews involved in Russia’s bomb project. Jews like Oppenheimer felt that the Soviet Union needed the bomb because the Soviets were doing all of the fighting before America opened up the western front in June of 1944.

Sixth, Oppenheimer was driven by guilt. This becomes clear in his relationship to Jean Tatlock. The only way Oppenheimer could expiate his guilt was by collaborating with sacred Jewish causes like Communism and later Zionism.

Nolan’s understanding of Oppenheimer differs from Bird’s in American Prometheus. Jew is a category shorn of content in Bird’s biography, which simultaneously brings up and plays down the Jewish angle, but even he is forced to turn the Oppenheimer security clearance hearings which lie at the heart of both film and book as manifesting “the ugly spectre of anti-Semitism” in a way that was not unlike “the ordeal of Captain Alfred Dreyfus in France in the 1890s.”[ii] Bird manifests the same “ambivalence about his Jewish identity”[iii] that Oppenheimer manifested during his life. The Oppenheimers were German Jews who had assimilated in Germany and were equally determined to assimilate in their new home in the United States. Bird sees significance in the letter “J” in the name J. Robert Oppenheimer, insisting like his subject that “his first initial stood for nothing at all.”[iv] If “J” stands for Jew, we are told that “Jewish traditions played no role in the Oppenheimer household.”[v] This empty category was filled by modernity. Nolan emphasizes Oppie’s love of modern art. According to Bird, the Oppenheimers “acquired a remarkable collection of French Postimpressionist and Fauvist paintings chosen by Ella. By the time Robert was a young man, the collection included a 1901 ‘blue period’ painting by Pablo Picasso entitled Mother and Child. . . .”[vi]

The main vehicle for the Oppenheimers’ assimilation into American culture was the Ethical Culture Society, a “non-religion” which was founded in 1876 by Felix Adler as an outgrowth of American Reform Judaism.[vii] Adler’s “non-religion,” according to Bird, would “have a powerful influence in the molding of Robert Oppenheimer’s psyche, both emotionally and intellectually.”[viii]

In a sermon called the “Judaism of the Future,” Adler claimed that the Jews had to renounce their “narrow spirit of inclusion” and “distinguish themselves by their social concern and their deeds on behalf of the laboring classes.”[ix] Adler was referring of course to communism and socialism, the primary manifestations of the Jewish revolutionary spirit in Oppenheimer’s lifetime. There is no reason to doubt Bird’s claim that “Robert’s adult political sensibilities can easily be traced to the progressive education he received at Felix Adler’s remarkable school,”[x] but, as we have already mentioned, Jew is an empty category in Bird’s book, and “progressive” is in this instance a euphemism for the Jewish revolutionary spirit. When Oppenheimer was a young man, “progressive” referred to the Jewish coup d’état known as Bolshevism, which seized control of Russia in 1917. Communism dominated Jewish thinking for the entirety of Oppenheimer’s adult life. Opppenheimer was 13 years old at the time of the Russian Revolution, and he died in 1967, at the age of 62, just as the Jews got fed up with the Civil Rights Movement and shifted their allegiance to Zionism because of the Arab-Israeli war.

Bird claims that “Adler’s radical notions of Jewish identity struck a popular chord among wealthy Jewish businessmen in New York precisely because these men were grappling with a rising tide of anti-Semitism in nineteenth-century American life.”[xi] But the exact opposite was the case. Anti-Semitism was on the rise because Jews were perceived as revolutionaries who were prepared to overthrow the government of the country which had granted them asylum from the pogroms of the Czar. By the 1920s, before the immigration act of 1924 was put into effect, the Jews who had escaped the pogroms were swept up into a euphoria over the Bolshevik Revolution that was all but universal among the hoard of Jewish immigrants who had come to America during the previous three decades. Bird typically misreads this situation by referring to America’s revulsion at Jewish revolutionary agitation as “mounting bigotry.”[xii] Getting even more specific, Bird dismisses the legitimate concerns of the American people as “nativist Christian bigotry”[xiii] and as a result blinds himself to the true nature of the conflict which would find expression during the early 1950s when Jewish betrayal of highly sensitive classified information became too big to ignore. The crucial issue was whether the Soviets were going to get the atomic bomb, and Oppenheimer’s divided psyche would play a crucial role in that drama.

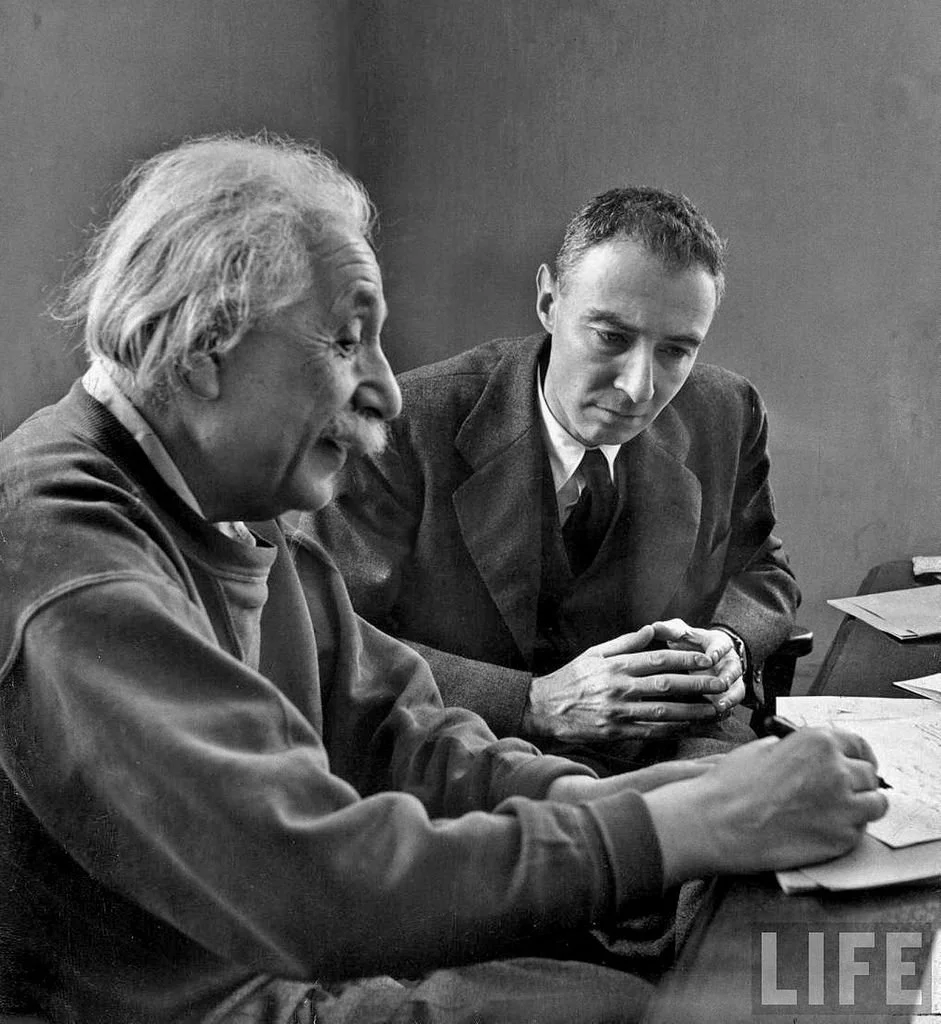

Albert Einstein and Oppenheimer

Bird claims that Oppenheimer “was uncomfortable with being identifiably Jewish,”[xiv] but he fails to see how “social concern” and “deeds on behalf of the laboring classes” allowed Jews simultaneously to assert and deny their Jewish identity by submerging it in a movement that was deliberately internationalist in scope. Trotsky, who denied his Jewish identity by abandoning his Jewish birth name and adopting the name of his Russian prison warden, is the paradigmatic example of deliberate denial of traditional Jewish ethnocentrism and its replacement by aggressive assertion of the Jewish revolutionary spirit in its place. Trotsky was the model for Jewish communists of the 1930s even after Stalin expelled him from the Soviet Union he helped create.

And it was precisely in the 1930s when Oppenheimer made the contacts with the Communist Party which would plague him for the rest of his life. As Aldous Huxley pointed out in his memoir Ends and Means, liberation from sexual morality had philosophical and political implications:

I had motives for not wanting the world to have a meaning; and consequently, assumed that it had none, and was able without any difficulty to find satisfying reasons for this assumption. The philosopher who finds no meaning in the world is not concerned exclusively with a problem in pure metaphysics. He is also concerned to prove that there is no valid reason why he personally should not do as he wants to do. For myself, as no doubt for most of my friends, the philosophy of meaninglessness was essentially an instrument of liberation from a certain system of morality. We objected to the morality because it interfered with our sexual freedom. The supporters of this system claimed that it embodied the meaning—the Christian meaning, they insisted—of the world. There was one admirably simple method of confuting these people and justifying ourselves in our erotic revolt: we would deny that the world had any meaning whatever.[xv]

The abandonment of meaning led to immorality, which then led to guilt, and guilt, in the absence of sacramental confession, led to political activism. In his memoir of the 1930s The God that Failed, Stephen Spender is even more specific. Communism in the 1930s provided an engine which would anaesthetize conscience. It went hand in hand with “the philosophy of meaninglessness” which Huxley described:

This doubly secured Communist conscience also explains the penitential, confessional attitude which non-Communists may sometimes show towards orthodox Communists with their consciences anchored—if not petrified—in historic materialism. There is something overpowering about the fixed conscience. There is a certain compulsion in the situation of the Communist with his faith reproving the liberal whose conscience swings from example to example, misgiving to misgiving, supporting here the freedom of some writer outside the Writers’ Syndicate, some socially-conscienceless surrealist perhaps, here a Catholic priest, here a liberal professor in jail. What power there is in a conscience which reproaches us not only for vices and weaknesses but also for virtues, such as pity for the oppressed, if they happen to be the wrong oppressed, or love for a friend, if he is not a good Party member! A conscience which tells us that by taking up a certain political position today we can attain a massive, granite-like superiority over our own whole past, without being humble or simple or guilty, but simply by virtue of converting the whole of our personality into raw material for the use of the Party machine![xvi]

Oppenheimer was no exception to that rule. Guilt made its appearance in Oppie’s life at around the same time he got involved in left-wing politics. Sex was the vehicle. Bird tells us that Oppie’s affair with Communist Party member Jean Tatlock, who was only 22 years old when Oppie met her in the spring of 1936,[xvii] “‘opened the door’ for Robert into this world of politics.”[xviii]

Huxley and Spender have already explicated the psychic alchemy which transformed sexual liberation into guilt and guilt into revolutionary politics. Sexual liberation led to guilt, which then led to involvement in revolutionary politics, which became the sacred cause which expiated guilt. The Holocaust Narrative played a role here as well. Oppenheimer, according to his own admission, “had a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany,”[xix] which heightened his attraction to the Soviet Union, which was doing the brunt of the fighting against Nazism until 1944.

By the 1930s, Freud and Marx had become fused in the minds of Jews like Wilhelm Reich as two sides of the same revolutionary coin. Jean Tatlock, who was both a member of the Communist Party and a psychiatrist, was no exception to this rule. Members of Communist circles in California at the time began to notice the influence that Tatlock’s fusion of Freud and Marx were having on Oppie, who had always been sympathetic to both strains of Jewish revolutionary thought. Wolfgang Pauli complained to Isidor Rabi that Oppenheimer “seemed to treat physics as an avocation and psychoanalysis as a vocation.”[xx] Edith Arnstein, a friend of Tatlock’s and a member of the Communist Party, “sensed that Oppenheimer’s politics were always driven by the personal” even if she couldn’t explain the main source of his personal guilt explicitly. Instead of talking about his affair with Tatlock as the source of his guilt, Arnstein claimed that “he felt guilty about his gifts, about his inherited wealth, about the distance that separated him from others.”[xxi]

Long before he had the blood of innocent Japanese civilians on his hands, Oppie saw psychoanalysis as a way of relieving himself from the guilt which accrued from his sexual behavior:

Oppenheimer’s exploration of the psychological was encouraged by his intense, often mercurial, relationship with Jean Tatlock—who was, after all, training to become a psychiatrist. . . . Moody and introspective, Tatlock shared Robert’s obsession with the unconscious. Furthermore, it made sense that Oppenheimer the political activist would choose to study psychoanalysis under the tutelage of a Marxist Freudian analyst like Dr. Bernfeld.[xxii]

While he was still sexually involved with Jean Tatlock, Oppie showed up unannounced at a party in San Francisco with a married woman by the name of Kitty Harrison on his arm. Harrison was “Oppie’s most recent lover”[xxiii] but not his last, and their appearance together turned the party into what another communist called “a not altogether happy occasion.”[xxiv] Oppie married Kitty Harrison after she became pregnant with his child. When Oppie called Kitty’s husband, to inform him of that fact. Dr. Harrison responded by telling the FBI that “he and the Oppenheimers were still on good terms and that he realized that they all had modern views concerning sex.”[xxv]

Bird shares those modern views concerning sex, which dooms his analysis of Oppenheimer’s character to superficialities which miss the main point, which is that Oppenheimer’s sexual behavior created the guilt which drove him first to psychoanalysis and then to collaboration with the communists and finally to the compulsive attempts at exculpation which drove his behavior during the McCarthy era…

[…] This is just an excerpt from the Oct 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

Warning: Reading the Gospel May Cause Anti-Semitism by E. Michael Jones

Features

Oppenheimer: Applied Jewish Science by E. Michael Jones

Reviews

Moving on Skiffle by Van Morrison by Sean Naughton

(Endnotes)

[i] Oppenheimer, at 10:00 [ii] Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Vintage, Reprint 2007), Amazon Kindle. [iii] Bird, p. 25. [iv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 28. [v] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 28. [vi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 28. [vii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 34. [viii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 34. [ix] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 35. [x] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 39. [xi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 36. [xii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 36. [xiii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 36. [xiv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 48. [xv] “Aldous Huxley, Quotes, Quotable Quote,” Goodreads, Quote from Ends and Means, https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/465563-i-had-motives-for-not-wanting-the-world-to-have [xvi] Stephen Spender, et al. The God that Failed (New York: Harper and Row, 1949), p. 241. [xvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 175. [xviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 182. [xix] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 180. [xx] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 199. [xxi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 196. [xxii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 199. [xxiii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 240. [xxiv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 240. [xxv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 253. [xxvi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 619. [xxvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 48. [xxviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 213. [xxix] “American Prometheus,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Prometheus [xxx] “Steve Nelson (activist),” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Nelson_(activist) [xxxi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 214. [xxxii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 207. [xxxiii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 382. [xxxiv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 386. [xxxv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 386. [xxxvi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 386. [xxxvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 61. [xxxviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 69. [xxxix] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 73. [xl] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 74. [xli] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 108. [xlii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 113. [xliii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 128. [xliv] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile: Recollections of a Life with Werner Heisenberg, Trans. S. Cappellari and C. Morris (Boston: Birkhäuser, 1984), p. 40. [xlv] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik (Munich: Piper, 1992), p. 79. [xlvi] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 10. [xlvii] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, pp. 10-11. [xlviii] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, pp. 10-11. [xlix] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 71. [l] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 71. [li] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 72. [lii] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 72. [liii] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, p. 45. [liv] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 74. [lv] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 75. [lvi] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 74. [lvii] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 75. [lviii] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 14. [lix] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 16. [lx] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 17. [lxi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 259. [lxii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 262. [lxiii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 264. [lxiv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 264. [lxv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 264. [lxvi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 267. [lxvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 268. [lxviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 268. [lxix] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 413. [lxx] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 414. [lxxi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 433. [lxxii] “Joseph Rotblat,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Rotblat [lxxiii] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, p. 82. [lxxiv] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 165. [lxxv] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 163. [lxxvi] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, p. 74. [lxxvii] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, p. 74. [lxxviii] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, p. 74. [lxxix] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 157. [lxxx] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 159. [lxxxi] Werner Heisenberg, Deutsche und Jüdische Physik, p. 162. [lxxxii] Elizabeth Heisenberg, Inner Exile, 109. [lxxxiii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 338. [lxxxiv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 479. [lxxxv] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 502. [lxxxvi] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 590. [lxxxvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 590. [lxxxviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 664. [lxxxix] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 888. [xc] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 889. [xci] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 889. [xcii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 858. [xciii] “Edward Teller,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Teller [xciv] “Lewis Strauss,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Strauss [xcv] “Nuclear Weapons and Israel,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_weapons_and_Israel [xcvi] Zionist Onslaught, “Israel & Assassination of The Kennedy Brothers (Laurent Guyénot),” YouTube, Sept. 16, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kzz9Md0d76Y&t=3s; Laurent Guyénot, The Unspoken Kennedy Truth; Avner Cohen and William Burr, “How a Standoff With the U.S. Almost Blew Up Israel’s Nuclear Program,” HAARETZ, May 3, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-how-a-standoff-with-the-u-s-almost-blew-up-israel-s-nuclear-program-1.7193419 [xcvii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 726. [xcviii] Bird, American Prometheus, p. 821. [xcix] Norman Finkelstein, “The Mask is Off: Why Ukraine Will NEVER Be a NATO Member,” Norman Finkelstein’s Official Substack, https://normanfinkelstein.substack.com/p/the-mask-is-off