Is Beauty Really in the Eye of the Beholder?

/E. Michael Jones, The Dangers of Beauty: The Conflict Between Mimesis and Concupiscence in the Fine Arts (South Bend: Fidelity Press, 2022), Hardback, 459 pages, ISBN 978-0-929891-29-3

Well, this will be no news to fans of E. Michael Jones, but he has done it again! He’s written another masterpiece. Let’s just pray that he keeps riding his bike and swimming at the local pool so that he lives a long time to keep giving us these treasure troves of literary genius.

The only thing I didn’t like about the book was its title; not because it was a bad title, but because it didn’t do justice to the outstanding content inside. After reading the whole book, and since “beauty” is the focus, perhaps a more intriguing title could have been: “Is Beauty Really in the Eye of the Beholder?” or “The Mystery of Beauty in Art: What is it and How and Why Does it Affect Us?” or “The Mystery of the Arts: What are Paintings, Music, Poetry and Literature Really Saying to Us?”

The book has a 14-page Introduction, and four main sections: (1) Painting in Italy (92 pages); (2) Music in Germany (18 pages); (3) Poetry in England (86 pages); and (4) Jewish Modernity (166 pages), with comprehensive endnotes and index. Unfortunately, I had to be judicious about the length of my review because if I could comment on all the parts worthy of highlight, my review would be voluminous and more like Cliff Notes than a book review.

What You Get Out of the Book

As is the case with all of Michael’s books, the reader gets a well-rounded education in many fields of knowledge. In order to understand art, you must also understand some philosophy, which is why the book starts with Plato and Aristotle. But don’t worry. Michael gives what you need to know about these two Greek philosophies in order to see how they affect our understanding of art. It is no coincidence that, as almost everything else divides with Plato on one side and Aristotle on the other, from the get-go the understanding of art begins with the dichotomy dictated by these two disparate philosophies.

But in order to understand art you also need to know about culture, politics, science, sex, money, theology, music, theater, poetry, cinema, because they all interconnect. Fortunately, Michael fills in the gaps most of us have in our present knowledge on these subjects so you can follow his bread crumbs very easily.

The most fascinating dimension of the book is that Michael gives you a secret view into the inner workings of the human psyche, the very psyche that produces the art. After he is done educating you with his 459 pages of one-of-a-kind tutelage, you will be able to look at a painting, a drawing, and a photograph; or read a poem or piece of literature; or listen to a piece of music; or study a piece of architecture, and you will be able to tell what it is saying to its audience; not perfectly, but at least Michael will start you down that path. That ability alone is worth the price of the book.

The Men Behind the Art

An even more fascinating part of the book—as would be expected from a communicator who knows there is always more behind the story than what one sees on the surface, especially regarding human follies and foibles behind the demise of some of the greatest artists in history—The Dangers of Beauty often reads like the National Inquirer, but at the scholarly level. Michael lets no stone unturned as he peels off layers of human tinsel to get to the real person behind the art.

Michael tells you the inside story of how and why someone was either successful or fell off the proverbial tracks, which often leads to discovering their sexual orientation; whether their marriages were good or bad; who their friends were that influenced them; who supported them financially; what their childhood was like; whether they really had talent or not; who were their enemies; whether they drank to excess, smoked pot, or took LSD; from whom they plagiarized or who plagiarized them; what their psychological hang ups were; their religion, ethnic background; and what they should have said or thought but didn’t.

By the time Michael is done analyzing a popular figure, you feel like you’ve known him/her their whole lives (and in some cases you wish you hadn’t known them). In other words, when Michael Jones deals with a man of the arts, he deals with the complete man, the man behind the curtain, the very curtain that the rest of the secular world has been holding in place so they can continue to give praise and adulation to some of the most notorious human delinquents ever to dot our history.

Some of the more famous people, listed here in random order, that Michael analyzes, for good or bad, include: Plato and Aristotle (Greek philosophers); Pablo Picasso (Cubism artist); Terry Eagleton (Oxford Professor, literature), Rick Rubin (Rap artist); Richard Schechner (Drama professor, NYU); Carl Jung (psychoanalyst); Boethius (Platonic philosopher); Giotto (early medieval artist); Leon Alberti (Platonic philosopher); William of Ockham (Nominalist philosopher); Sandro Botticelli (Italian painter); Tiziano Vecellio (aka Titian, Italian painter); Pietro Aretino (Italian painter); The Council of Trent on Art; Frederico Borromeo (cardinal); Michelangelo (Italian artist); Peter Paul Rubens (Dutch painter); Georg Handel (German composer); Antonio Vivaldi (Italian composer); Giovanni da Palestrina (Italian composer); Johannes Bach (German composer); Ludwig von Beethoven (German composer); Jean-Antoine Watteau (Flemish painter); Julien La Mettrie (French painter); Francois Boucher (French painter); Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Sir Philip Sidney, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, Sir Joshua Reynolds (English writers, poets); Johann Fichte, F.W.J. Schelling, Georg Hegel, Immanuel Kant (German philosophers); Jane Austen (English writer); Richard Wagner (German composer, of whom Mark Twain said: “Wagner’s music is really better than it sounds”); Eduard Hanslick (Jewish music critic); John Henry Newman (cardinal); Matthew Arnold (English poet); Arnold Schönberg (German composer); Richard Gerstl (German painter); Clive Bell (English art critic); Albert C. Barnes (American art critic); Mark Rothko (modernist painter); Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (German art promoter); John Cage (modernist composer); Jackson Pollack, Andy Warhol (modernist painters); Joseph Hauer (German musician); Wassily Kandinsky (German painter); George Gershwin (American composer); Pope Pius X; Rev. Garrigou-Lagrange (French theologian); Aidan Nichols (English Catholic priest-philosopher); Jacques Maritain (French Catholic philosopher); Nicholas Nabokov (Russian composer); Etienne Gilson (French Thomist philosopher); Ezra Pound (American poet); T. S. Eliot (English poet); Hugh Kenner (English literary critic); Central Intelligence Agency (promoter of Abstract Expressionism art); Leo Castelli (art promoter); William de Kooning (modernist artist); Jasper Johns (American modernist artist); Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian composer); Leonard Bernstein (American Jewish composer); Marc Blitzstein (American Jewish composer); Aaron Copeland (American Jewish composer); Igor Stravinsky (Russian composer); Nicholas Nobokov (Russian composer); Julius Fleischmann (CIA art promoter); Mortimer Adler (Jewish Thomist); Bertrand Russell (English philosopher); Philip Roth (American Jewish writer); John Updike (American writer); Stanley Kubrick (American film maker); Garry Winogrand (American Jewish photographer); Robert Mapplethorpe (American Jewish photographer); Mathilde Krim (American art promoter); Alfred Hayes (English Jewish poet); Stanley Fish (American Jewish writer); Jacques Derrida (French Jewish philosopher); Aldous Huxley (English writer); Michael Foucault (French philosopher); Noel Ignatiev (American professor); Philip Johnson (American architect); Peter Eisenman (American Jewish architect, writer); Philip Bess (American-Catholic architect, writer); Stanley Tigerman (American Jewish architect); Thomas Gordon Smith (American architect); Frank Gehry (American Jewish architect).

Leonard Bernstein: The Man Behind the Mask

The best examples of Michael’s penetrating analysis that would fit into my allotted words and time boiled down to a choice among: Terry Eagleton (b. 1943), an uppity Cambridge-educated professor of literature now at Oxford University who is a literary critic and former Catholic turned Marxist, who married a Mormon and then divorced her, and who exhibits such interesting peccadilloes as admitting that, “The Church’s irrational fixation on sexual matters forced me to become a Marxist,” which sexual escapades, he admits, led to “venereal infections circulating almost as rapidly as theories of neo-colonialism. Erection and insurrection became giddyingly confused, and the organization was like a cross between a commune and a harem…young women fresh from convent school and anxious to compensate for their class crimes” (pp. 191-7; 320-44).

Second in the running was Pablo Picasso, who, between his serial romances and his grotesque Cubist art, one never knows what he wants or what he is even looking for in life. At times, he portrayed humankind as so insignificant that the viewer can’t tell the human figure apart from the inanimate objects. All was one mass of confusion. One of the first examples of his extreme abstraction was his 1907 painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, (“The Young Ladies of Avignon” who are depicted as naked prostitutes). When Picasso showed this eight-foot-square canvas to a group of painters and art critics at his studio, there was shock and outrage. Matisse was enraged and considered it a hoax. Derain said, “One day we shall find Pablo has hanged himself behind his great canvas.” Salmon, the art critic, wrote: “It was the ugliness of the faces that froze with horror the half-converted.” Apparently, Picasso had the same sentiments, since he stated that Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was “my first exorcism painting...if we give spirits a form, we become independent.”

Despite the boos from his peers, Picasso eventually found art promoter Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who, as Michael notes, “with typical Jewish perspicacity” showed Picasso how “to make money out of borderline pornography masquerading as fine art” which “saved Picasso from financial ruin and he was full of gratitude that his decadent art had been saved by Jewish business acumen. ‘What would have become of us,’ Picasso said of his friend, ‘if Kahnweiler hadn’t had a business sense?’” ... “Kahnweiler’s promotion of Cubist works made him one of the most influential art dealers of the 20th century…pivotal to the movement’s success….Objectively speaking, Cubism was a Jewish marketing strategy…in which the art dealer succeeded the painter as the most influential figure in the art world” (p. 237).

And then there was Leonard Bernstein, who most people know from his musical score in the popular 1950s play and 1960s movie, West Side Story, still so popular that a modern version was produced by Hollywood just a couple of years ago. Since a book review should only do one of these artists, I eliminated Eagleton because he is not well known; and eliminated Picasso because everyone already knows he was crazy. Bernstein was the best to display the power of the book since Michael rips off the façade this American composer has enjoyed for more than half a century. Bernstein also best symbolizes the Jewish-Marxist takeover of the arts (and sciences) in the 20th century, even though some of the Jewish architects, like Peter Eisenman and Stanley Tigerman, are honorable mentions (pp. 344-387).

To cover the Bernstein story, Mike quotes mainly from Joan Peyser’s 1998 book, Bernstein: A Biography and the 1971 book, The New Music: The Sense Behind the Sound. As our heart strings are tugged when Tony and Maria sing the American version of Romeo and Juliet, we find out that Bernstein plagiarized at least three of the tunes. As Michael reveals:

Leonard Bernstein

…Bernstein got ‘Tonight’ from Benjamin Britten and ‘Somewhere’ from the second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5. Bernstein lifted the tune for ‘Maria’ from Blitzstein’s opera Regina, and the choral piece ‘Officer Krupke’ was saved from banality largely because of the wit and power of Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics (p. 285).

The Blitzstein referred to is Marc Blitzstein, a fellow composer and friend at Harvard who loved to distort music by using the 12-tone chromatic scale—an avant-garde music scale that Michael explains at length in the beginning of the book. We learn from Michael that “Marc Blitzstein epitomized the cultural trifecta of ‘queer, commie, Jew’ even better than Bernstein….Bernstein’s other mentor was Aaron Copland, another American composer who conformed to the same trifecta of commie, queer, and Jew” (p. 278)…. “Like Einstein, the physicist who epitomized Jewish science, Lenny [Bernstein] was a creation of the Jewish owned New York Times” of which “Peyser assures us that ‘no one in the music business in the United States has more power than the chief critic of the New York Times’” (p. 280). Bernstein basked in the press’ promotion, once declaring, “It is important to him that a composer is a Jew, that a performer is a Jew” (Peyser, Bernstein, p. 446).

Michael continues:

Because the United States needed Jewish support for the Anti-Communist Crusade, media outlets like the New York Times and CIA fronts like TIME magazine, never mentioned that Commie and Jew were synonyms. Instead, ‘Time ran an article in its October 22, 1945, issue in the gee-whiz style it reserved for its culture heroes: The 27-year-old wunderkind of the musical world, Leonard Bernstein, opened his fall season last week’ (Peyser, Bernstein, p. 156).

Curiously, Bernstein’s homosexuality was hidden when he married a Chilean Catholic, Felicia Montealegre in the early 1950s. Critics are divided as to whether Bernstein was sincere about his marriage or was just taking on a “beard”—the code word for homosexuals taking a wife to appear normal to the public and further their careers (NB: homosexuals don’t like body or facial hair)…

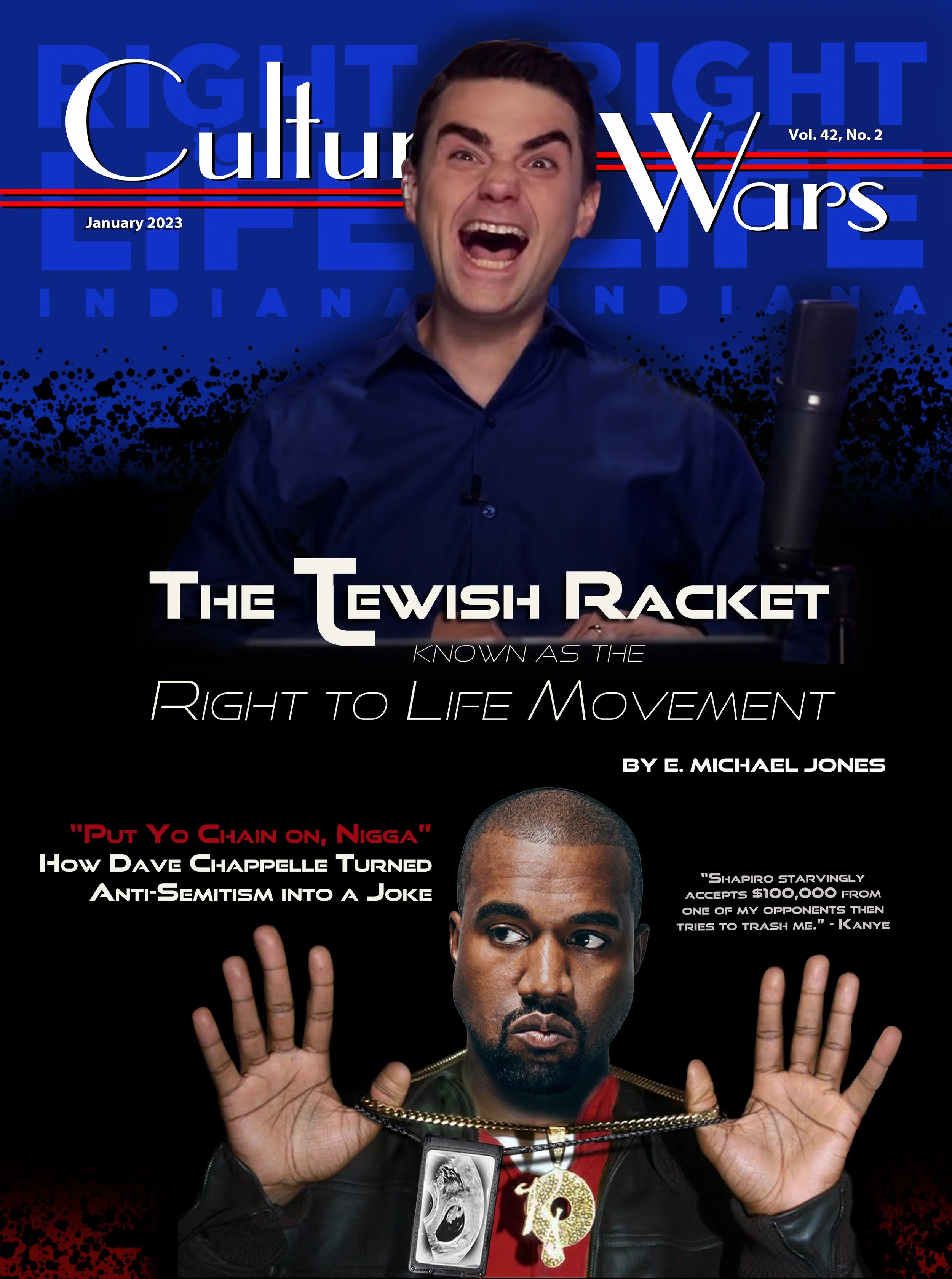

[…] This is just an excerpt from the January 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

(Endnotes Available by Request)