Moving on Skiffle by Van Morrison

/Exile Productions – Virgin Music (Released March 10, 2023)

Van Morrison achieved rock perfection back in 1970. When the age of rock ‘n roll faces its general judgement and all that mayhem, death and destruction is weighed in the balance, Side 1 of Moondance might just give the Almighty, well, at least a moment’s pause for thought before the ground opens up and the whole dastardly operation is consigned to the everlasting flames. Here we have five of the great songs, songs that allow the surviving hippies – soon to face their own particular judgement – to explain to their grandchildren, “My darlings, we sensed that we were venturing into forbidden territory, but you must understand… Van Morrison absolved us of any guilt. Listen!”

“And It Stoned Me” absolves the midnight tokers from any charge more serious than a sincere desire to once again encounter the world with all the innocent intensity of childhood. “Moondance” absolves the lascivious midnight gyrators from any charge more serious than staying up rather later than usual – ‘making love’ retains all its original amorous innocence. “Crazy Love” is a sublime hymn to the insane intensity of a man loving a woman. “Caravan” tells us that love is ever old and ever new. “Caravan” also provided the greatest rock moment ever captured on film, namely Van the Man’s 1976 appearance in all his rhinestoned barrel-chested drop-kicking glory at the Winterland Ballroom in LA for The Last Waltz with the Band. And the side ends with “Into the Mystic.” Thank you, Van.

“Into the Mystic” is the perfect song. Insofar as a rock song can, it ticks every box in the list of beauty’s attributes, not least a kind of understated splendour, borne along on an absolutely gorgeous bass line. Anyone whose played in a band knows that feeling of euphoria that hits when things just come together, and this is somehow communicated to the listener as the song builds from the lone acoustic guitar opening through the tense “foghorn” vibratos and the two gloriously bluesy brass interludes, to the clean, almost abrupt ending. And then there’s that voice – he’s called “the Man” not just for the rhyme but for a reason. He’s in charge and you better listen because this is serious; Van the Man has seen further and ventured deeper than anyone else. He is an authority. He’s a veritable muezzin of the mystical. He makes Jim Morrison (no relation) sound like an over-excited schoolboy showing off his new leather trousers, bragging about half-baked notions of breaking on through to the other side. Van Morrison has been on the other side. Heck, he’s practically on first name terms with the Infinite, and now he’s deigning to tell us about it, so just be quiet and listen, OK!

Just as the wheels were coming off the hippie bandwagon and the bodies were piling up, this song was Van’s valiant attempt to restore some kind of respectability to proceedings. Yes, says Van, you can be spiritual without being religious. Ironically, it was the man who loathed hippies who came closest – by way of “Into the Mystic” – to capturing the essence of the hippie dream. Now that we know – thanks to E. Michael Jones – what we didn’t know then, namely the extent to which the whole thing was an orchestrated assault on that whole generation, we can still reminisce about the more idealistic, benign vision that was so seductive. Everyone wants to find the shortcut to Heaven. Everyone wants to reach the end of that road (or maybe it’s a stairway) that we all want to walk, that one with the blinding light at the end, and that’s neither too narrow nor too steep, and blissfully free of thorns. Can I achieve union with the Infinite holding hands with this beautiful girl? Can’t we stay forever on this misty mountain top? That feeling of beatitude is enhanced by, you know, a few drinks and a little smoke – and songs like “Into the Mystic” – but it feels very real. The only snag is that it’s temporary. What’s a young man to do?

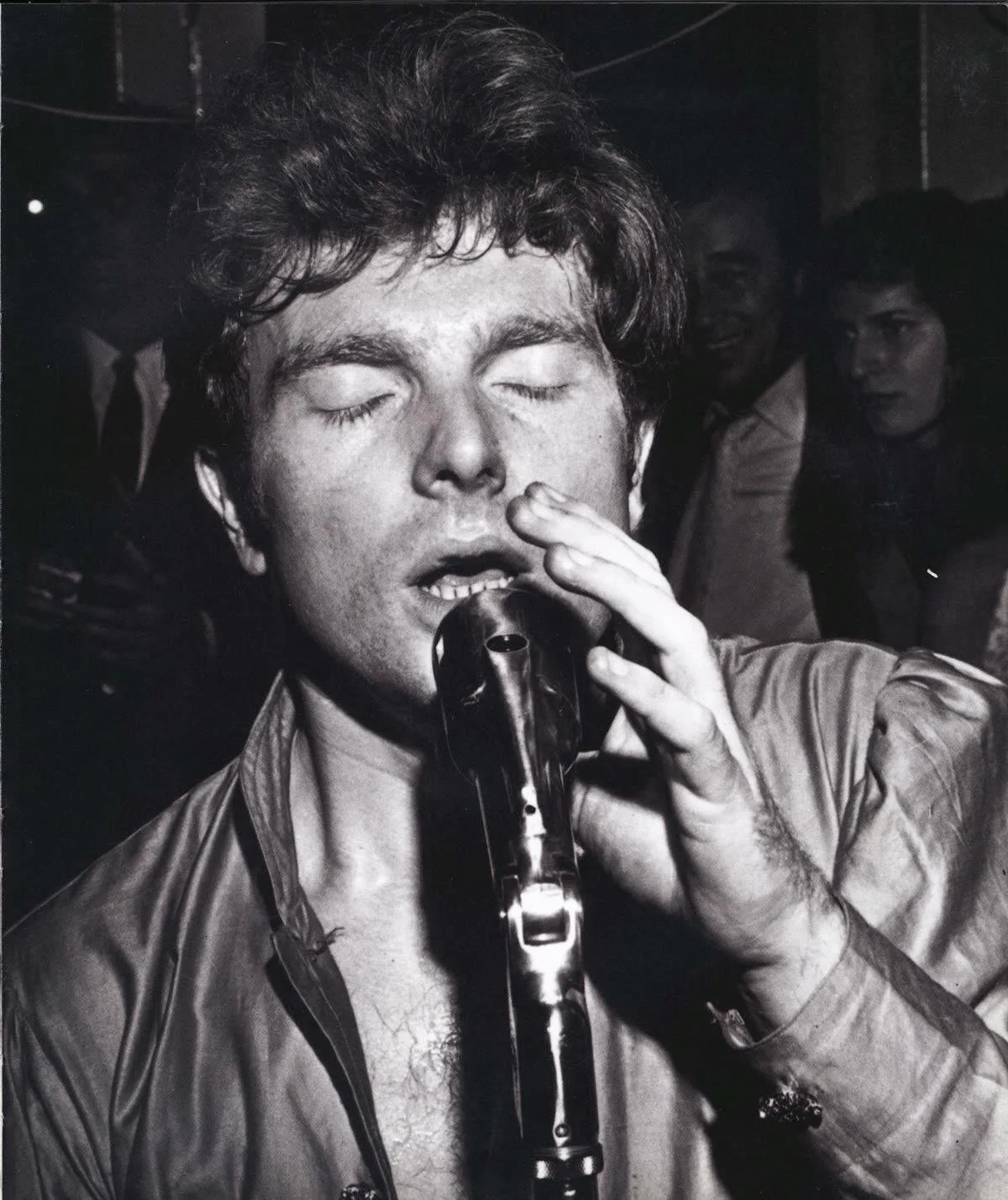

Van Morrison

Having launched into the mystic and now returned to terra firma, it’s decision time. Do I dedicate myself to recapturing the bliss – that’ll take more drink and harder drugs, and heavier music, and delusions that sex is the missing ingredient –or do I see the bliss for what it is: a taster of the Eternal? That’s where marriage, that Earthbound exercise in eternity, comes in. On the other hand, making the wrong decision at this point gives rise to what’s known as the hippie nightmare. By 1970 the news of the nightmare was well out. Sharon Tate and her pre-born baby were dead, and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin would be dead within the year, with Jim Morrison breaking on through on a permanent basis a year after that. Led Zeppelin turned the nightmare vision into the darkest and most disturbingly seductive rock music ever made. Who knew that being dazed and confused could sound so good? And anyway, maybe Hell is the preferred destination for the more discerning pilgrim. Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven, right? By the time punk came around the whole game was up, and we’ve been in rehash mode ever since. We should’ve quit while we were behind.

When it came to decision time for Van Morrison, he decided to have his cake and eat it too. Who can blame him? He got to marry the hippie beauty and he got to keep making the music. Not bad going for a deranged, ginger-haired, reclusive, balding, paranoid, under-sized misanthrope from East Belfast. Then he had to face a question unique to rock stars – what’s more important, the music or the marriage? Two divorces and some sixty albums later, it is hardly necessary to spell out the gory details. So where did it all go wrong? “Into the Mystic” provides a tantalizing clue in the closing bars of the song, which itself reaches perfect musical resolution immediately after this intriguing cri de coeur: “Too late to stop now.” That versatile little line sounds like a declaration of undying love. But it also serves quite nicely as an apology or an excuse, or a last-gasp exclamation, or, God forbid, an epitaph. Now if a man is going to give a lyrical hostage to fortune like that, sooner or later he deserves to get punished. If he doesn’t die young like his namesake Jim Morrison, or stay married like his father George Morrison Sr, eventually he’s going to have to answer the question, “OK Van, what about now? Still too late to stop?” With the release of Moving on Skiffle – 23 cover versions of vintage Americana – Van Morrison’s 44th studio album, the question becomes a plea. Van, you might think it’s too late, but can you stop now! Please.

Van may have peaked with “Into the Mystic,” but marriage and the birth of a child brought forth Tupelo Honey in 1971, Van’s celebration of continued and committed crazy love. But like so many of his fellow titans of rock, he took his “too late to stop now” philosophy too far. Rather than a declaration of undying love, it became an excuse for wretched excess and, in Van’s case, psychotic levels of insecurity-induced control freakery as first wife Janet “Planet” describes:

He doesn’t like a lot of people around. With more than two people he gets uncomfortable. He doesn’t like the idea of all those people looking at him. Really, he is a recluse. He is quiet. We never go out to parties, we never go out. We have an incredibly quiet life and going on the road is the only excitement we have.[i]

By the end of 1973 even going on the road as a family couldn’t save the marriage:

By then our life together was very traumatic and horrible […] I couldn’t stand any more of his rage as my daily reality. I worried about its implications on the children [...]I couldn’t reconcile the fragile dream with the emotional chaos which kept intruding and crashing everything down.[ii]

The end of his first marriage coincided with the last of his best music. He might’ve had a home and a family life but he ended up on the road, and, treating his bands much the same way he treated his wife, they became the abused surrogate families on which he has depended to this very day. Van had already been on the road as a musician since the age of 15 when he played saxophone with a showband called the Monarchs. That’s a total of – wait for it – 63 years on the road as a musician. This reality is the best way to approach Moving on Skiffle. At the risk of stating the obvious, Moving on Skiffle finds Morrison making merry on the theme of movement. He’s positively raving about the joys of journeying, reveling in the sheer abandon of being restless, on the road, and on the run. In fact, these 23 songs provide an uncannily accurate biography of the man himself, as well as a portrait of the artist as an old man. The first track is “Freight Train”:

Freight train, freight train, goin’ so fast

Freight train, freight train, goin’ so fast

I don’t know what train I’m on

Won’t you tell me, ‘fore I’m gone

Lost his reason, lost his life, killed his friend in mortal strife

Must have moved like the rolling skies

Just a-waitin’ until he dies

The lyric change from the 1907 Elizabeth Cotten original is our first encounter with Van’s readiness to indulge the poetic license he appropriates as skiffle pioneer, grand old man of rock, and knight of the realm. Having said that, lyric changes are part and parcel of the skiffle tradition. The skiffle repertoire is drawn from American roots music – blues, spirituals, mountain music, negro work songs and the like – mixed up and shaken with folk songs from the British Isles, and any catchy three chord tune that could be dug up or tracked down. Van Morrison’s 2023 reworking is just the latest in a long line of ever-changing renditions. To get a sense of both the provenance and the impact of skiffle – of which more later – “Freight Train” is an Exhibit A example. In 1957, Glaswegian Chas McDevitt, one of the original “skiffle kings,” took the original – a simple hymn to the American dream of escaping slavery of one kind or another – and created this manic, even panic-stricken ballad of a killer on the run. Such was the success of the Nancy Whisky / Chas McDevitt 1957 release that it earned them an American tour and an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show[iii] that same year. Moving on Skiffle is a kind of Morrison legacy project, fulfilling his desire to re-present to the world the skiffle songs that meant so much in the 1950s, but which languish unloved and rarely visited in their YouTube retirement home.

In paying homage to this foundational music, Moving on Skiffle sees Van rolling out the red carpet and breaking open the champagne, thereby producing a lushness that all too often crosses the line into cheery, cheesy karaoke. To the extent that the songs are skiffle, we have music at its most oxymoronic. The spirit of skiffle is stripped down guitar-bass-washboard “three chord thrash.”[iv] “Moved on” skiffle, á la Van Morrison, involves ten highly accomplished musicians producing Americana at its most diabetic, and with the irritating, retro, call and response backing vocals, Americana at its most bloated. If he’d gone all in and done an “Into the Mystic” brassed-up r ‘n b version, we’d have something to get our teeth into, but this is just sugar with no substance. Having cut his musical teeth playing saxophone in an Irish Showband – a horn section was compulsory for these suited ‘n booted highly accomplished mobile juke-boxes – Van knew how the marriage of brass and the blues brings forth that delightfully mature Morrison sound that was his early ’70s hallmark. Fifty years on, the bouncy yet brassless cabaret sound which pervades the whole album is the musical equivalent of happy talk. It’s as if the band is trying to talk up the whole project just to keep the perennially morose Morrison from jumping in front of that oncoming freight train.

Led Zeppelin

Continuing the murder theme, Track 2 brings us the more commonplace reason for taking the train, namely, “Careless Love.” It’s a thin line between crazy love and careless love, and when that line is crossed it might be a good idea to catch the next train out of town. The railroad narrative continues with, let’s see, Tracks 4, 9, 10, 11, 19 and 21. Whether it’s freight trains or streamlined trains or streamlined cannonballs, the landscape of the album is criss-crossed with railway lines, interwoven with rivers, canals and green rocky roads. Don’t get me wrong, I love train songs, but call me old fashioned, a train is supposed to run not bounce. In any case, as far as the train is concerned, I think we get the message. Just like the horse for the cowboy, or the motorcycle for the Hell’s Angel, or Van’s erstwhile favourite, the caravan for the eternal gypsy, the train represents “freedom” which in the lexicon of Americana means extrication from a sticky situation. E. Michael Jones includes that highly evolved caravan – the motorhome – in this ever-expanding list of means-of-escape modes of transport, and provides a penetrating insight into what all this talk of trains is really about:

As we sat in the 21st century version of the Conestoga wagon and watched America’s landscape roll by at the stately Conestoga pace of 50 miles per hour…the main topic of discussion was what do you do when you have ruined your life.[v]

Jones goes on to tell us that divorce is one of the best ways to ruin your life. American music is equal parts fuel for the fornicator and medication for the divorced. This album is a cabinet full of the latter, with a few doses of the former for good measure. OK Van, we get the message. Let it be said, that one thing that Van cannot be faulted for is his taste in songs to cover – his 1971 version of Bob Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman” is absolutely sublime, and his country selection from 2008’s “Pay the Devil” is vintage country gold. And he hits the mark here again with his selection of maybe the greatest ever song in the OK-have-it-your-own-way divorce category, which also happens to be a serious contender for greatest ever train song. The only tenuous evidence that it was ever a skiffle number is its attribution to Johnny Duncan’s “Bluegrass Boys” in 1958.[vi] Nevertheless, this Hank Snow classic is undoubtedly the theme tune for the whole album:

I’ve told you baby from time to time

But you just wouldn’t listen or pay me no mind

Now I’m movin’ on, I’m rollin’ on

You’ve broken your vow and it’s all over now

So I’m movin’ on

You switched your engine, now I ain’t got time

For a triflin’ woman on my main line

‘Cause I’m movin’ on, you done your daddy wrong

I’ve warned you twice, now you can settle the price

Cause I’m movin’ on

You know a song hits the sweet spot when those martyrs to monogamy, The Rolling Stones, do a version (1965), as does one-timer Elvis Presley (1969) who was something of a slouch compared to three-timer Emmylou Harris (1982). Once again, Van’s conga-driven boogie-woogie version is just too bouncy for a train song. The undisguised glee of Track 19 provides a chuckle-inducing contrast to Van’s more somber 2018 reaction to divorce Number 2:

At my age, I have found it to be a hugely wearying, protracted experience and I’m relieved that it has finally reached a conclusion.[vii]

What’s a septuagenarian songster to do with hugely wearying, protracted experiences that have finally reached a conclusion? Track 21 provides the solution in the form of “Worried Man Blues.” If it’s good enough for serial fornicator Woody Guthrie, it’s good enough for Van Morrison. But aren’t you supposed to at least sound worried Van? Nope, says Van, it’s my party and there’ll be no crying round here! Van transforms “Worried Man Blues” into ‘Rhapsody for the Relieved’ and his legion of divorced fans bow down in homage.

“I’m Movin’ On” has the cuckquean and all the cuckolds heading south. E. Michael Jones begs to differ and identifies an even more liberating direction of travel. Calling to mind that earlier topic for discussion, namely, “What do you do when you have ruined your life?” we learn that:

America has various answers to that question, and most of them have to do with the West, which is where you go when your past becomes too complicated.[viii]

That’s all very well for an American to say, but for an Irishman – even an Ulster Protestant like Van Morrison – there’s a small matter of the Atlantic Ocean to consider. Having said that, the Atlantic Ocean proved to be no obstacle when it came to the British Invasion. By the time the 1970s hit, those uber-warriors of English rock, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page and Robert Plant had already immortalized Jones’ conclusion:

Spent my days with a woman unkind

Smoked my stuff and drank all my wine

Made up my mind to make a new start

Going to California with an aching in my heart

Someone told me there’s a girl out there

With love in her eyes and flowers in her hair

(Track 7, Led Zeppelin IV, November 1971)

By that time, Van Morrison was also California-bound, leaving Woodstock with his California flower girl, the aforementioned Janet Planet nee Rigsbee, herself a divorcee, brought up by a single mother who had left Corpus Christi Texas and moved – you guessed it – westward to San Francisco to bring up her child. Van’s sense of the American West as a dreamland was long in the making. For us tail-end baby-boomer Irish, the Wild West was the favoured destination for our flights of fancy as children. We were all cowboys. Six-guns with holsters and cowboy hats and sheriff’s badges and spurs were the stuff of Christmas ecstasy, birthday dreams and summer days driftin’ on the prairies. Van the Man the boy seemed destined to enter the Cowboy Hall of Fame. If the persona of the cowboy represents self-sufficiency, silence and a certain alienation from normal society, Van was in training from his earliest days. As an only child who grew up in Protestant East Belfast with a determinedly irreligious father and a Jehovah Witness convert as a mother, Van Morrison, a self-confessed “complete recluse”[ix] as a child, was an outsider even in his own home town:

Young Morrison was a preternaturally quiet boy whose lack of siblings meant that he had no immediate role models on whom to practise his social skills. Introspection was an easier option.[x]

The interior world inhabited by the boy Morrison was populated by characters drawn mainly from the American West. His readiness as a teenager to identify with luminaries from Leadbelly to Jack Kerouac becomes all the more inevitable in light of Morrison’s early identification with America in general and in particular with the cowboy:

As an only child, Morrison’s isolation was heightened when his father left the family to find work in America […] After a lengthy period employed as a railroad electrician in Motor City, the wandering father returned home armed with a collection of records and presents for the family. Young Ivan, who already owned a shelf full of Wild West stories, was delighted to receive a cowboy outfit with the name Tex Ritter emblazoned on the chaps…[xi]

[…] This is just an excerpt from the Oct 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

Warning: Reading the Gospel May Cause Anti-Semitism by E. Michael Jones

Features

Oppenheimer: Applied Jewish Science by E. Michael Jones

Reviews

Moving on Skiffle by Van Morrison by Sean Naughton

(Endnotes)

[i] Johnny Rogan, Van Morrison: No surrender, London: Secker & Warburg 2005, p. 273. [ii] Rogan, p. 277. [iii] MrSamascot, “Freight Train,” YouTube, Dec. 20, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3N4srNjyRK0 [iv] Billy Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, Faber & Faber. Kindle Edition, p. 11. [v] E. Michael Jones, Travels with Harley: In Search of America Motorcycles, War, Deracination, Consumer Identity, South Bend: Fidelity Press 2011, p. 6. [vi] Chas McDevitt, Skiffle: the Definitive Inside Story, London: Robson Books 1997, p. 263. [vii] Ivan Little, “Van Morrison tells of ‘relief’ after divorce,” Belfast Telegraph, March 2018, https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/news/van-morrison-tells-of-relief-after-divorce/36742484.html [viii] Travels with Harley, p. 6. [ix] Clinton Heylin, Can You Feel the Silence?: Van Morrison A New Biography, Chicago: A Capella Books and imprint of Chicago Review Press (2002), p. 11. [x] Rogan, p. 16. [xi] Rogan, p. 17. [xii] Rogan, p. 23. [xiii] Heylin, p. 9. [xiv] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 333. [xv] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 333. [xvi] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 106. [xvii] McDevitt, p. 10. [xviii] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 43. [xix] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 106. [xx] E. Michael Jones, The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit, South Bend: Fidelity Press (2008), p. 841. [xxi] Barney Hoskyns, Trampled Under Foot: The Power and Excess of Led Zeppelin, Faber & Faber. Kindle Edition pp. 5-6. [xxii] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 415. [xxiii] Bragg, Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, p. 426. [xxiv] Hoskyns, p. 6. [xxv] McDevitt, p. 37. [xxvi] My Collection, “Jimmy Page - ‘All Your Own’ TV Show April 6, 1957,” YouTube, Aug. 7, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewNLaBhPRY8 [xxvii] Chris Salewicz, Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography, Harper Collins Publishers. Kindle Edition, pp. 428-429. [xxviii] Rogan, p. 122. [xxix] Salewicz, pp. 50-51. [xxx] Salewicz, p. 51. [xxxi] Rogan, p. 111-112. [xxxii] Kenneth Grahame, Wind in the Willows, London, Penguin 2005 (Original published 1908) p. 1. [xxxiii] Grahame, pp. 18-19. [xxxiv] Rogan, p. 344. [xxxv] Rogan, pp. 353-354. [xxxvi] Heylin, p. 362. [xxxvii] Heylin, p. 375. [xxxviii] Heylin, p. 475. [xxxix] Dionysos Rising, p. 149. [xl] Dionysos Rising, p. 150. [xli] Salewicz, p. 13. [xlii] Salewicz, p. 97. [xliii] Kory Grow, “Robert Plant on Success, Getting Panned by Rolling Stone, and What ‘Stairway to Heaven’ Means to Him Now,” Rolling Stone, Aug. 25, 2022, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/robert-plant-alison-krauss-led-zeppelin-1396022/ [xliv] Van Morrison, “Haunts of Ancient Peace,” Genius, https://genius.com/Van-morrison-haunts-of-ancient-peace-lyrics [xlv] Van Morrison, “Whenever God Shines His Light,” Lyrics, https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/101728/Whenever+God+Shines+His+Light [xlvi] Turner, p. 142. [xlvii] Barney, Hoskyns, Small Town Talk: Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix & Friends in the Wild Years of Woodstock, Faber & Faber. Kindle Edition, p. 175. [xlviii] Daniel Kreps, “Eric Clapton’s Anti-Vaccine Diatribe Blames ‘Propaganda’ for ‘Disastrous’ Experience,” Rolling Stone, May 16, 2021, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/eric-clapton-disastrous-vaccine-propaganda-1170264/ [xlix] Dave Everley, “Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, and the alarming rise of the Covid conspiracy rock star,” LOUDER, July 30, 2021, https://www.loudersound.com/features/eric-clapton-van-morrison-and-the-perplexing-rise-of-the-covid-conspiracy-rockers [l] E. Michael Jones, Libido Dominandi: Sexual Liberation and Political Control, South Bend, Indiana: St Augustine’s Press (2000), p. 9. [li] Jones, p. 15. [lii] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, Legend Library Classics Edition: Kindle Edition, location 1098-1044.