The Other Dangers of Beauty in the Life and Works of Jorge Luis Borges

/¿Quién me dirá si en el secreto archivo de Dios están las letras de mi nombre? (Who will tell me whether God's secret file has the letters of my name?)

– Góngora, Jorge Luis Borges

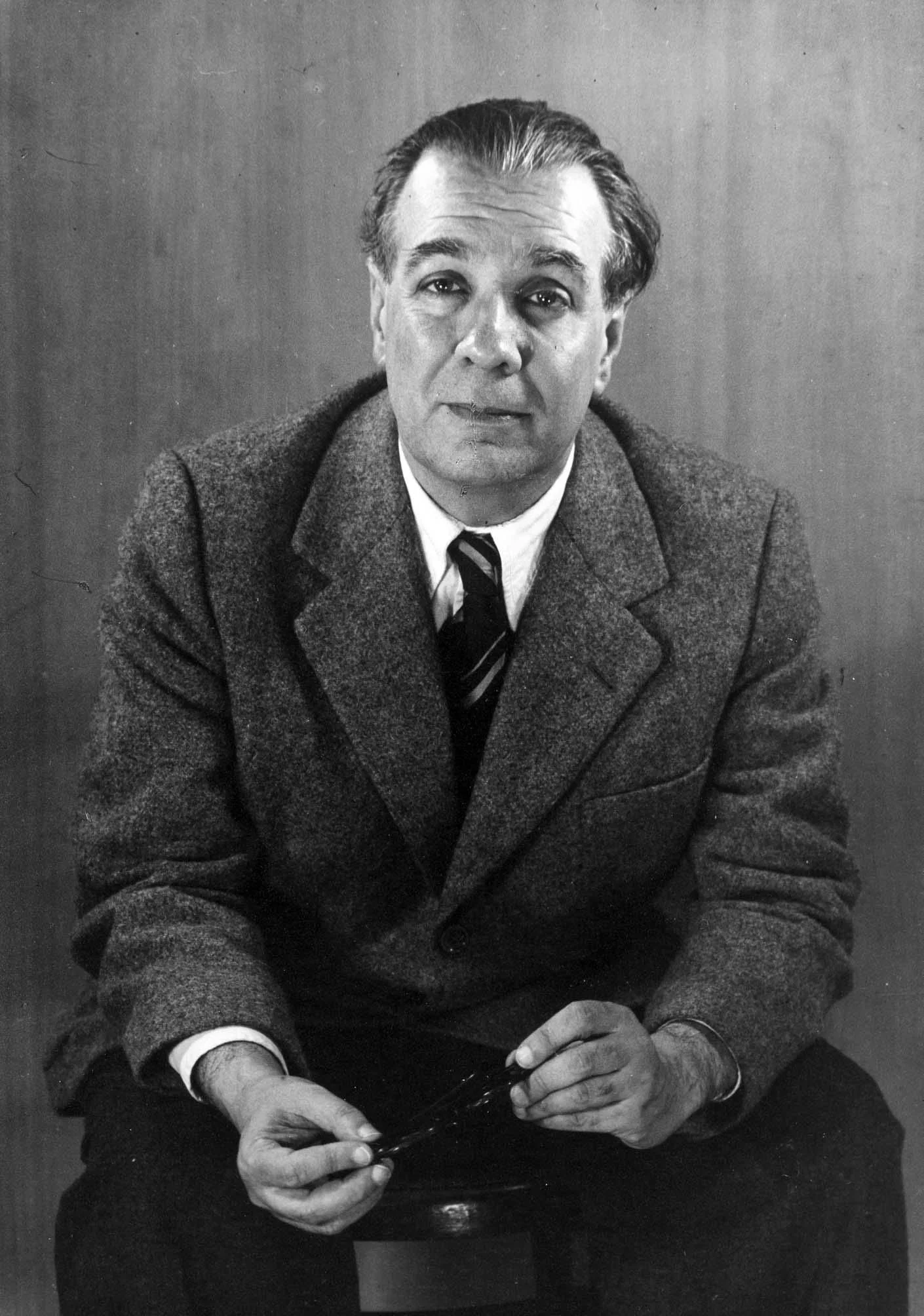

Jorge Luis Borges

Introduction

How can beauty be dangerous? Maybe because it may lead those who lack it to jealousy and envy, and those who have it to misuse it?

In the realm of art, especially the modern ersatz version of it, another downside can be concupiscence.[1] That is what E. Michael Jones expounds in his new work,[2] whose paradoxical title is answered by a subtitle that spills the beans of the book’s thesis.

Good art is not dangerous, rather the opposite, it elevates. But the art, whether sacred or profane, that was once the inheritances and glory of Christendom has been deliberately abandoned by academia and the mainstream media and pushed away from the public sphere.

This did not happen by chance. Jones explains how, why, when and who by tracing through history four main streams of western art: painting, music, poetry, and architecture. It is a history of a slow organic rise and a fast manufactured fall, which means there must be a peak somewhere in between.

Identifying a period of “peak art” is to some degree arbitrary, and it also depends on the genre in question. For example, I am tempted to locate peak music at the time Wagner wrote Parsifal, but I am just a layperson. Others may choose Gregorian chant.

In the light of The Dangers of Beauty and her elder brother Logos Rising,[3] the dictum of politics being downstream from culture (or is it the other way around?) becomes moot because both are downstream from religion (or morality, a derivative of religion). This shows up time and again.

In Logos Rising we learnt that Christendom reached its peak in the late Middle Ages, around the time of Thomas Aquinas. And it set the stage for art and science to flourish. Yet after the Scholastics came the confusion of Nominalism, which in turn informed the Reformation, which was followed by the French Revolution. At this point the decline moved from gradual to fast and accelerated further with the Bolshevik and sexual revolutions of the 20th century. The current ongoing revolution against nature itself is just the logical consequence of this trend.

Peak morality, in other words, precedes peak art. The waxing of the morality arc precedes by several centuries the waxing of painting and music. And so do the waning stages. This trajectory is more than a mere correlation; it is cause and effect with a lag contingent upon the inertia of history and civilizations. Morality is upstream from culture. Morality informs culture.

And that is why the Revolution promotes hip-hop and shuns Beethoven, and why Mark Rothko is endorsed at the expense of Michelangelo, and gender theory replaces Shakespeare. It is only a bad deal if you are not aware of the scam, because there are formidable weapons at our disposal in the culture wars which allow us to have a fulfilling and happy life if you know where to find them, and The Dangers of Beauty guides you in the right direction.

Some readers may roll their eyes here, but they do it at their own risk, and that of their families. During the Covid-induced confinements, in what seems a case of jumping out of the frying pan into the fire, the pornographic site Pornhub is said to have had more visits than Amazon and Netflix combined. Pornography is an extreme form of the dangers of beauty, when degraded in the hands of the unscrupulous. We underestimate what we (and our) children watch and listen at our own (and their) risk.

Yet, while concupiscence is a real danger and one that threatens most people, it is not the only danger of beauty. The sins of the flesh are not the worst; that distinction belongs to the sins of the spirit. This allows us to complement Dr. Jones work by introducing the Argentine poet Jorge Luis Borges to Culture Wars’ readers.

The beauty of Borges

Borges (1899-1986), born in Buenos Aires and arguably among the best poets in Spanish together with Francisco de Quevedo, Ruben Dario, and a few selected others, uncannily embodies the conflict stressed in The Dangers of Beauty. The beauty part, we shall see, is unmistakable. The danger does not come from concupiscence, though.

Augustine thought that beauty originated from God Himself. Beauty, as understood by the Scholastics, is a transcendental together with truth and goodness − and part of the ultimate reality known on earth as Logos and in heaven as the Beatific Vision.[4] Beauty is not subjective but results from the harmonious reconciliation of unity and diversity,[5] diversity understood not as a Human Resources apparatchik would.

The poet is superior to both the philosopher and the historian because he creates beauty by coupling the general notion (the essence) with the particular case (the existence).[6] When well chosen, words have so great a force in them, that they often give us more lively ideas than the sight of things themselves.[7] Borges knew a thing or two about it.

Poetry defined by William Wordsworth as “emotion recollected in tranquility”[8] is for Borges “verbal music.”[9] The beauty of Borges is not just in the elegance and precision of his concise verses, which are studiously not bombastic. You must read them carefully to get the rhyme. It is also in the capacity to abridge and summon entire ideas and centuries of history with a few stanzas. An example of the latter is his ode to Spain (España, 1964) where among other things he tells us[10]:

23 España de la larga aventura

24 que descifró los mares y redujo crueles imperios

(Spain of the long adventure / that deciphered the seas and subdued cruel empires)

Deciphering and seas may not match at first glance, but that is what the Spanish (and Portuguese) did when they launched the age of discovery. They figured out the complex wind and current patterns of the oceans at different latitudes. To get to the Americas they first had to sail south and then west to catch the easterly (trade) winds. To get back to Spain they had to first head north and then east to get the westerlies as tailwind. A puzzling pattern of seasonal and hemispheric dependent gyres, that eventually took them as far as Tierra del Fuego and Alaska. The “cruel empires” are the slavery-driven kingdoms of South and Mesoamerica, which routinely engaged in human mass sacrifice, especially the Aztecs. Spain did not just subdue them, but she also evangelized their populations.

In El Golem (1958), Borges packed philosophical and magic undertones that caught the eye of many, including Umberto Eco of The Name of the Rose fame. These are the first two stanzas[11]:

1 Si (como afirma el griego en el Cratilo)

2 el nombre es arquetipo de la cosa

3 en las letras de 'rosa' está la rosa

4 y todo el Nilo en la palabra 'Nilo'.

5 Y, hecho de consonantes y vocales,

6 habrá un terrible Nombre, que la esencia

7 cifre de Dios y que la Omnipotencia

8 guarde en letras y sílabas cabales.

(If, as the Greek maintains in the Cratylus, / a name is the archetype of a thing, / the rose is in the letters that spell rose / and the Nile entire resounds in its name’s ring. / So, composed of consonants and vowels, / there must exist one awe-inspiring word / that God inheres in-that, when spoken, holds / Almightiness in syllables unslurred.

This is Borges at his best, and one of his favorite poems[12]. Verse 1 is a reference to the Greek philosopher Plato. Platonic realism stands for the existence of universals or abstract objects. Universals were considered by Plato to be ideal forms (archetypes, hence confusingly also known as Platonic idealism). The next three verses beautifully encapsulate the realist position[13], later challenged by medieval nominalists. Nominalism says that only particulars are real, that there are no universals, which are arbitrary “nominal” words, just names. For nominalists there are just individual roses, more so the Rose could be named River, and vice versa without detriment; but Borges begs to differ here and elsewhere in his work.[14]

It is an impressive introduction, and a misleading one as well, for in the next stanza Borges takes us to a very different place. It is still about “names,” although not as discussed by Greek or Christian philosophers, but as envisaged in Jewish esoteric mysticism. Verses 5 to 8 are a reference to the Kabbalistic belief that the cosmos was built from the twenty letters of the Hebrew alphabet. If man can learn how God went about His creation, he too will be able to create human beings and perform miracles. The secret of God’s creation is presumably in the Torah [Pentateuch], which is as a whole the one great Name of God, even if no one knows its right order. For the sections of the Torah are not given in the right arrangement, known to God alone. The Kabbalists strove to find that hidden order that would mimic by magic the Divine act of creation, and this is the origin of the legend of the Golem, which means “unformed matter.”[15]

Verse 8 shows the genius of Borges and his command of the Spanish language. Syllables “cabales” is a pun between the meaning of the words cabal and cábala. In Spanish the word cabal means complete, correct, exact, precise, appropriate, and derives from the Latin caput (head). The word cábala (Kabbalah in English) comes from Hebrew and means “tradition.” Were it not for the accentuation, in Spanish they are almost homographs and homophones, that is, almost identical in writing and pronunciation (and thus perfect for rhyme), but totally different in origin and meaning. Giving the reader a clue of what is coming next, Borges superbly conjures the Hebrew-originated word cábala while using the Latin-derived word cabal which also fits the context like a glove.

What comes next is Borges parody of the legend of the Golem.[16] After a life of trial and error the rabbi utters the “Name that is the Key” but what he manages to create is but a “simulacrum” of man. Something went wrong, “perhaps the sacred name had been misspelled.” Among other flaws, the Golem never learnt to speak, the poor creature does not have logos. The Kabbalist Rabbi “who played at being God” fails miserably and God certainly does not approve, “Who is to say what God must have been feeling/Looking down and seeing His Rabbi so distressed?”

In The Golem Borges anticipates the transhumanist ambitions of “ye shall be as gods,” nowadays pushed by the likes of Yuval Noah Harari, as well as the inexorable failure that follows afterward.

Borges has been criticized for being all form and little content.[17] But in this case, we must disagree. There is beauty and substance here. He wrote more than 400 poems, and many of them are exquisite.

The problem with Borges

The problem with Borges can be traced to tension between the teachings of his devoutly Catholic mother and a Presbyterian grandmother against the influence of a free-thinking father, which introduced him to bad philosophy and dragged him into agnosticism.

As noted by Antonio Planells, agnosticism is a very comfortable philosophical stance and indication of an idle metaphysical attitude, which cannot be hidden no matter how sophisticatedly it is disguised.[18] Beyond the admiration Borges may inspire, his foundations are weak, because his philosophy is based on spiritual disorientation and confusion.[19] Borges is on the record stating that although he was “very interested in philosophy and metaphysics” he considered them “forms of fantastic literature”[20]; and that he esteemed “religious or philosophical ideas for their aesthetic value”[21]; and that in his early years he tried to believe in a personal God, but later he gave up.[22] You get the gist.

It gets worse, while Borges writes within a Christian frame of reference, his attitude towards Christian orthodoxy is consistently conflicted. .[23] In fact, Borges’ worldview is not compatible with a Christian conception of the world.[24] He disparages the doctrine of the Trinity as “a useless theological Cerberus.” He is offended because it defies human rationality, especially the irreconcilable opposition between the notions of the eternal Father and his Son, held to be equally divine yet conceived in time. In poems the Trinity is mentioned several times, from a neutral de facto tone such as “God, who is Three and is One”[25]; to derision such as a “curious God, who is three, two, one.”[26]

God is not to be trusted anyway; he is either far away inaccessible and indifferent,[27] or worse lurking “al acecho,”[28] and even ruthless.[29] In the poem “Jonathan Edwards,” God is referred to as a Spider in the center of the web. [30] The reader may object and point that it is Jonathan Edwards, a Puritan with a Calvinist outlook, who engages in such theological conjectures. And he may be right, yet a constant device in Borges’ late poetry is the monologue where he impersonates another’s voice in the poem, making him say what Borges actually thinks.[31] It gets difficult to tell the “lyrical I” from Borges.[32]

The danger of Borges

Christ appears frequently in Borges poetry,[33] usually in three personas. According to Lucas Adur the most recurrent is the Crucified persona, highlighting the human features of Jesus, his mortal condition and death. The second persona is that of Jesus as a teacher or poet, depending on whether his speech is considered as ethics—his doctrine of forgiveness, the Sermon on the Mount—or aesthetics—his parables, the novelty of his metaphors. In both cases, Jesus is considered from a non-religious perspective, as a historical figure of indisputable relief, but human. The third persona is that of the Incarnate Word: Jesus is presented as God made man, which does introduce a supernatural component, although, the divinity of Christ appears more as a presumption than as an article of religious faith. In all cases references to miracles and resurrection remain completely absent.[34] An example of this are two beautiful poems entitled Juan, I:14[35] where Borges deals with the implications of the verse: “And the Word was made Flesh and dwelt among us.”

The poem “Cristo en la cruz” (Christ on the Cross, 1984) is essential to understand Borges view of Jesus. Here are the key verses.[36]

5 El rostro no es el rostro de las láminas.

6 Es áspero y judío. No lo veo

7 Y seguiré buscándolo hasta el día

8 ultimo de mis pasos por la tierra.

…

14 Cristo en la cruz. Desordenadamente

15 piensa en el reino que tal vez lo espera,

16 piensa en una mujer que no fue suya.

17 No le está dado ver la teología,

18 la indescifrable Trinidad, los gnósticos,

…

25 Sabe que no es un dios y que es un hombre

26 que muere con el día. No le importa.

…

29 Nos ha dejado espléndidas metáforas

30 y una doctrina del perdón que puede

31 anular el pasado.

…

34 Ha oscurecido un poco. Ya se ha muerto.

35 Anda una mosca por la carne quieta.

36 ¿De qué puede servirme que aquel hombre

37 haya sufrido, si yo sufro ahora?

(His face is not the one seen in engravings. / It is severe, Jewish. I do not see it. / and I will keep on searching for it / until my last step on earth. … Christ on the cross. Chaotically / he thinks about the kingdom that perhaps awaits him, / he thinks about the woman who was not his. / He is not able to perceive theology, / the indecipherable Trinity, the Gnostics, … He knows that he is not a God and that he is a man / who dies with the day. It makes no difference. … He has left us some splendid metaphors / and a doctrine of forgiveness that can / do away with the past. … Night has fallen. He has died now. / A fly crawls over the still flesh. / Of what use it is to me that this man has suffered, / if I am suffering now?)

General Augusto Pinochet of Chile

Early on, verses 5-8, Borges concedes that while he cannot see or has not found Christ yet, he will keep trying as long as he lives. This is an encouraging start and could have been said by many a devout Christian in a moment of trial (the poem “The Dark Night of the Soul” by Saint John of the Cross comes to mind). Unfortunately, things go downhill from there.

The “perhaps” on verse 15 that makes Jesus express doubt about who He is, is Borges speaking, not Jesus. The same applies to Jesus thinking of “a woman who was not his,” and allegedly not being able to understand theology and the Trinity at the very moment of achieving His redemptive mission for humanity. Borges is here projecting on Jesus his own limitations, miseries, and prejudices.

In verses 25-26, Borges hints that Jesus believed He is dying as a man, which is not a surprise because he was both man and God; but artfully slips in the idea that Jesus may have doubted whether He was also God, rather than just a man. Again, this has nothing to do with Jesus, but has the signature of Borges barren lucubrations.

In verses 29-31, Borges tell us he thinks Jesus was at most just a good philosopher, not unlike Confucius. At the end Borges reveals his view of Christ. His divinity is dismissed and His redemptive power denied[37].

Agnosticism and extreme skepticism may lead to desperation, ambivalence about the afterlife,[38] rage… and writing blasphemous poetry. Borges view of Heaven and Hell is not Christian,[39] in fact he says that no temporal action deserves eternal punishment or reward.[40]

Am I cherry-picking? Is this a biased selection? Having read Borges’ complete poetry it must be said that many of the references to God and Christ are not negative,[41] but the negative ones are defining and tend to be clustered in his last work.[42] I will spare the reader the anti-Christic travesty entitled “Fragments from an Apocryphal Gospel.”[43]

We will see there is more to Borges than his poetry. In the meantime, the reader will agree that whatever the Borgesian danger is, it is not about concupiscence. As a mere Borges enthusiast, I would argue that it comes from Borges’ pride and intellectual pretensions.

At this point it is relevant to recall Jones’s The Dangers of Beauty and the exploits of the so-called Bloomsbury group, with which Borges was acquainted.[44] A clique of English intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century who used the moniker “higher sodomy” to describe themselves. The idea was, presumably, to take a higher stance against reigning sexual norms, beyond their inclination to a more garden-variety “lower sodomy.”

By analogy, Borges’ danger then may be described as “higher blasphemy.” A subtle form of blasphemy that may not be recognized as such unless the reader possesses a minimum degree of theological awareness.

Leonardo Castellani (1899-1981), a Jesuit polymath contemporary of Borges, who knew his compatriot’s literary output very well, is arguably his most well-read and harshest critic. Castellani scrutinized Borges’ theological wanderings more than anybody else. Overall, Castellani acknowledges Borges’ sophistication in form and technique, although he finds its content twisted by an author who is ultimately an aesthete. He indicts Borges for sophistry, moral cowardice, and lack of genuine philosophical and theological understanding.[45]

Castellani accused Borges of blasphemy early on, mostly based on a reading of his prose[46] but noted that Borges’ blasphemies are “elaborate and reticent,”[47] “almost disguised,”[48] higher blasphemy indeed, as opposed to the coarser blasphemies of “[Giosuè] Carducci and Victor Hugo.”[49]

With many nuances and without the harshness of Castellani, a diverse array of critics who examined Borges view of God and Christ do not come to dissimilar conclusions.[50] At the end of the day, as Pedro L. Barcia surmises, Borges may leave atheists and believers alike dissatisfied.[51]

Defense of Borges

Beyond the beauty of his poetry and despite his flaws, there are several reasons to defend Borges. Even Leonardo Castellani, in many ways Borges’ nemesis, advised us to forgive Borges for his blasphemies because in the end they were few and disguised.[52]

Borges became completely blind by the age of 55. He had a cross to carry and he seems to have accepted it (together with the abundant talents he was also given) as deduced from the “Poemas de los dones” (Poem of the Gifts, 1960)[53]:

1 Nadie rebaje a lágrima o reproche

2 esta declaración de la maestría

3 de Dios, que con magnífica ironía

4 me dio a la vez los libros y la noche.

(No one should read self-pity or reproach / Into this statement of the majesty / Of God, who with such splendid irony / Granted me books and blindness at one touch.)

Borges is an equal opportunity mocker. He mocks everybody. The Jews are not exempted as seen in “The Golem,” where he laughs at the preposterous Jewish cabalists playing God. Neither are the Muslims, whom he scorns for having burned the library of Alexandria when Caliph Omar’s forces conquered Egypt in the seventh century.[54] Freud and the “subconscious” were not spared either.[55]

Borges never got the Nobel prize, probably due to political bias from the Nobel committee after Borges met General Pinochet. His open contempt of democracy, “that curious abuse of statistics,” sure didn’t help either.[56] Alas, Borges runs the risk of now being cancelled. He was cool and progressive back then. Now the Overton window has moved so far to the left among the chattering classes that he might become taboo, as happened to Rudyard Kipling, whom Borges admired. His personal conversations with Adolfo Bioy Casares are being minutely scrutinized by modern academics with an axe to grind.[57] Beauty is not a defense against the woke crowd. Neither his Anglophilia nor his alleged Philosemitism[58] may save him from this ordeal. Oblivion, a returning theme in his work, may await Borges after all.

Perhaps the most important motive to defend him is his late conversion...

Borges' conversion

Most of the poems with gloomy references to God or Christ are found in Borges later books, while most of his poems with positive allusions are found in his early work. This seems to indicate a trajectory and does not bode well for Borges because, as Alexander Solzhenitsyn[59] and E.M. Jones have pointed out time and again, what is in the soul of an artist will be bared, explicitly or implicitly, in his work.

Borges thought that “there is eternity in beauty,”[60] so he got one of the transcendentals right. Yet beauty can take you only to the Church’s threshold, not beyond it (E.M. Jones again). To enter (to believe) you need something else. That something else is grace, a gift from God, sometimes uncorrelated to other talents. Borges attempted that step at the very end.

How can this be explained considering that Borges did not attempt to redeem himself in the way that Wagner did by composing Parsifal after Tristan and Isolde, and returning to Logos later in his life? “Christ on the Cross” (1984) is his last important poem with Christ as the main theme.

Surely, fear of imminent death is said to “concentrate a man’s mind wonderfully,” especially among agnostics, no matter what nonsense you have written before. In addition, because Borges knew and disliked Blaise Pascal,[61] he certainly must have known Pascal’s wager, which argues for the reasonability of God’s existence.[62]

The story of Borges conversion is well documented and based on the accounts of a Swiss Catholic priest, Father Pierre Jacquet, who assisted Borges on his deathbed after being called by Borges’ family. [63] The only doubt that remains is how mentally lucid Borges was when confessing. According to Fr. Jacquet he was very weak, and it was not possible for them to have a conversation. Yet Borges manifestly understood what the priest was saying. At the end, complains Jaime Alazraki who witnessed the religious service conducted at the Saint Pierre Cathedral in Geneva, “Borges’ agnosticism surfaced as another piece of fiction.” The quote attributed to Thomas More “No one, on his deathbed, ever regretted having been a Catholic” comes very fitting, and more likely than not “God’s secret file does have the letters of Borges name.”

Conclusion

Should we read Borges’ poetry? Surely. Because of the abundant beauty, the numerous goodness, the frequent truth, and the occasional lie. It should be read together with a Castellani though, or a Chesterton, or better an Aquinas, not only to understand him better, but also to have the antidote to the doses of poison that Borges may introduce to the unsuspecting reader. Read from a Christian perspective, Borges induces a philosophical and spiritual protection analogous to the process of hormesis in toxicology: in small doses a little poison has a positive effect.

Borges’ beauty can take us closer to Logos, which is what ultimately matters here and beyond. Away from Logos, things turn ugly quickly, ugly as perversion and sin. In the here and now, we should share Jones’s metaphysical optimism while always keeping in mind that Tolkien’s “long defeat”[64] is something we have to live with in the meantime, and be prepared to be put in an iron cage as happened to Ezra Pound. END

[…] This is just an excerpt from the September 2023 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

Antony Blinken is a Holocaust Liar by E. Michael Jones

The Cancellation of Sinead

O’Connor: Ireland’s Tragic Princessby Geraldine Comiskey

Features

Why Hawthorne was Melancholy:

The “Lost Clew” Explained, Part II by Dr. E. Michael Jones

Reviews

The Other Dangers of Beauty in theLife and Works of Jorge Luis Borges by Octavio Sequeiros

(Bibliography)

E. Michael Jones, The Dangers of Beauty: The Conflict Between Mimesis and Concupiscence in the Fine Arts. South Bend: Fidelity Press, 2022, 459 p.E. Michael Jones, Logos Rising. A History of Ultimate Reality. South Bend, Fidelity Press, 2020, 784 p.Jorge Luis Borges. Poesía Completa. New York, Vintage Español, 2012, 647 p.Jorge Luis Borges. Selected Poems. Edited by Alexander Coleman. New York, Penguin Books, 2000, 484 p.Leonardo Castellani. Inquisiciones y sombras teológicas. Dinámica Social. N°33-34, Buenos Aires, mayo-junio 1953. Recogido en Lugones ; Esencia del liberalismo ; Nueva crítica literaria, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Dictio, 1976, pp. 188-193.Leonardo Castellani. Los grandes literatos perciben el fenómeno de lo demoníaco. Dinámica Social. N°67, Buenos Aires, abril 1956. Recogido en Lugones ; Esencia del liberalismo ; Nueva crítica literaria, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Dictio, 1976, pp. 194-200.Leonardo Castellani. Gracián y Borges. De Este Tiempo, Buenos Aires, N°5, año 1962. Recogido en Lugones ; Esencia del liberalismo ; Nueva crítica literaria, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Dictio, 1976, pp. 185-187. Leonardo Castellani. Borges. Verbo. N° 124, Buenos Aires, septiembre 1972. Recogido en Lugones ; Esencia del liberalismo ; Nueva crítica literaria, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Dictio, 1976, pp. 201-205.Leonardo Castellani. Crítica literaria; Notas a caballo de un país en crisis, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Dictio, 1974, 565 p. Pedro Luis Barcia. Borges según Castellani. Fuego y Raya, n. 23, 2022, pp. 85-99. Pedro Luis Barcia. Borges, trascendencia y religiosidad. En El Atrio de los Gentiles, La Plata, 2014, pp. 12-20.The Cambridge Companion to Jorge Luis Borges. Edited by Edwin Williamson. Cambridge University Press, 2013, 266 p. Jaime Alazraki. Borges and the Kabbalah: And Other Essays on his Fiction and Poetry. Cambridge University Press, 1988, 220 p.Antonio Planells. "Cristo en la Cruz" o la última tentación de Borges. 1990. Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica, Vol. 1, N. 32, Article 4.Antonio Planells. Jorge Luis Borges y el fantasma de Blas Pascal. Cuadernos Americanos, 11-9 (mayo-junio 1988), 175-197.Oswaldo E. Romero. Dios en la Obra de Jorge L. Borges: Su Teología y su Teodicea. 40 inquisiciones sobre Borges. Revista Iberoamericana, 1977, Vol. XLIII N 100-101, 465-501.Susana Chica Salas. Conversación con Borges. Entrevista en Revista Iberoamericana, vol. XLII, Julio-Diciembre de 1976, N. 96-97, p. 585-591.Amelia Barili. Borges on Life and Death. The New York Times. July 13, 1986. Section 7, Page 1. Fuente. Lucas Adur. Un dios despedazado y disperso. Imágenes de Jesús en la obra de Borges. Lexis Vol. XLII (2) 2018: 327-367.María Lucrecia Romera. La tradición religiosa en la poesía de Jorge Luis Borges. Rumbos del hispanismo en el umbral del Cincuentenario de la AIH. Hispanoamérica, 2012, Vol. 6, 302-312.Adolfo Bioy Casares. Borges. Edición al cuidado de Daniel Martino. Destino, 2006, 1664 p. Consultada la versión online de Epulibre. Edwin Williamson. Borges: a life. Viking, 2004, 592 p. Photos for articleJorge Luis Borges in 1919. Source: Emecé.Jorge Luis Borges in his older days. Source: Fundación Borges.Bloomsbury Group members Virginia Woolf and her brother-in-law, Clive Bell, in 1910. Source: New York Public Library.Fr. Leonardo Castellani. Source: Public domain.

(Endnotes)

[1] Concupiscence is understood generally as the inclination toward sin and evil (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 405) but more specifically here as the concupiscible side of sensuality as defined by Thomas Aquinas.

[2] E. Michael Jones, The Dangers of Beauty: The Conflict Between Mimesis and Concupiscence in the Fine Arts. South Bend: Fidelity Press, 2022, 459 p.

[3] E. Michael Jones, Logos Rising. A History of Ultimate Reality. South Bend, Fidelity Press, 2020, 784 p.

[4] Jones, ref. [1] p. 44.

[5] Jones, ref. [1] p. 44.

[6] Jones, ref. [1] p. 34.

[7] Jones, ref. [1] p. 38.

[8] Jones, ref. [1] p. 43.

[9] Borges, ref. [3] p. 160.

[10] In ref. [3] p. 244. Translated by myself.

[11] In ref. [3] p. 193. Translated by Alan S. Trueblood. Ref. [4] p. 193.

[12] In the prologue of Ref. [3] p. 12.

[13] Or more precisely that of Platonic extreme realism. Moderate realism, espoused by Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas among others, took an intermediate position between extreme realism and nominalism.

[14] “Así lo conjeturan los platónicos; así no lo aprobó Guillermo de Occam.” “So the Platonists surmise; thus William of Ockham did not approve” he tell us in the poem Correr o Ser (Poesía Completa, p. 560). Borges anti-nominalism is also highlighted in many other poems such as “La luna,” “Un poeta del siglo XIII,” “Baltasar Gracián,” “Everness,” “El advenimiento,” “La pantera,” “El conquistador,” “El tigre”; ref. [3] p. 121, 185, 189, 240, 366, 393, 447, 483 respectively.

[15] Alazraki. Ref. [13] p. 20.

[16] Borges main source was Gustav Meyrink’s novel Der Golem. Also, Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Ref. [13] p. 6, 14, 19, 35.

[17] Borges admits to having but dabbled in Kabbalah impenetrable texts, and his information is largely from secondary sources, which he read not with the fervor of a Kabbalist but as a fabulist with an interest in esoterica. Borges makes clear that it is not the doctrine itself that interests him, but its emphasis on the symbolic nature of language and cryptographic elements associated with it. Fishburn, E. Jewish, Christian, and Gnostic themes. Chapter 5 in Ref [12] p. 57.

[18] Planells. Ref. [14] p. 23.

[19] Planells. Ref. [15] p. 179.

[20] Chica Salas. Ref. [17] p. 586.

[21] Planells. Ref. [14] p. 25. Citing Borges “Epílogo” de Otras inquisiciones (1952).

[22] Barili. Ref. [18]. New York Times Online.

[23] Fishburn. Ref [12] chapter 5, p. 60.

[24] Barcia. Ref. [10] p. 93.

[25] In “Góngora” Ref. [3] p. 623.

[26] In “La Prueba” Ref. [3] p. 538.

[27] “Dios es el inasible centro de la sortija./ No exalta ni condena. Obra mejor: olvida.” In “La Moneda de Hierro” (The iron coin). Ref. [3] p. 469. Translated by Eric McHenry as “God is the unapproachable center of the ring./ He does more than exalt or sentence: he forgets” Ref [4] p. 387.

[28] “El camino es fatal como la flecha/ pero en las grietas está Dios, que acecha.” In “Para una versión del I King” (For a version of I Ching). Ref. [3] p. 462. Translated by Eric McHenry as “The road is fatal as an arrow’s flight/But God is watching in the narrowest light.” Ref [4] p. 383.

[29] In “El Otro” (The Other), ref. [3] p. 199, God is presented as ruthless (“despiadado”) for the ordeals with which he tests men.

[30] “Piensa feliz que el mundo es un eterno/ instrumento de ira y que el ansiado/ cielo para unos pocos fue creado/ y casi para todos el infierno./ En el centro puntual de la maraña/ hay otro prisionero, Dios, la Araña.” In “Jonathan Edwards (1703-1785)” Ref. [3] p. 221. Translated by Alan S. Trueblood as ”Blissful, he thinks the world an everlasting/ instrument of God’s wrath, the heaven all seek/ reserved for the happy few whom God acquits,/ the lot of everyone else the fires of hell./ In the very center of the tangled web/ another prisoner, God the Spider, sits.” Ref [4] p. 211.

[31] Wilson. J. The late poetry (1960–1985). Chapter 15 in Ref [12] p. 187.

[32] The poem “Baltasar Gracián” (Ref. [3] p. 189) is an egregious case of this trick. In fact, Leonardo Castellani states that Borges “projects,” as understood by modern psychologists, his own image onto Gracián’s. Ref. [7] p. 187.

[33] This work is based mostly on Borges poetry, not his prose, which is even harsher on Christianity.

[34] Adur. Ref [19]. p 361-362. Also ref. [14] p. 27.

[35] In Ref. [3] p. 202 and 295.

[36] In Ref. [3] p. 585. Translated by Alexander Coleman. Ref. [4] p. 471.

[37] See Barcia ref [11] p. 5; Fishburn ref [12] chapter 5, p. 62; Planells re [14] p. 35.

[38] For example, in “Blind pew,” “El despertar,” “Edgar Allan Poe,” “Los enigmas,” “Edipo y el engima,” “El mar,” “Elogio de la sombra,” “Una llave en East Lansing,” “A mi padre,” “Correr o Ser.” Ref. [3] p. 130, 203, 223, 227, 242, 257, 353, 440, 453, 560 respectively. If there was a transcendental that worried Borges it was eternity, but he emphasizes the eternity or immortality of the individual human spirit. See Barcia, Ref [11] p. 1.

[39] Barcia. Ref [11] p. 6, points the contradiction, first highlighted by Castellani, in Borges’ poem “Del Infierno y del Cielo” (Of Heaven and Hell) where the final verses say that the face of God “será para los réprobos Infierno/ y para los elegidos, Paraíso” (translated by Alastair Reid as “will be, for the rejected, an inferno/ and, for the elected, paradise.” Ref [4] p. 157). It is a contradiction because God cannot be two contrary things simultaneously.

[40] “Los actos de los hombres no merecen ni el fuego ni los cielos.” in “Fragmentos de un evangelio apócrifo,” ref. [3] p. 329. Translated by Stephen Kessler as “The acts of men are worthy of neither fire nor heaven,” ref [4] p. 293. Also, “Me creo indigno del Infierno o de la Gloria” in “Los enigmas,” ref. [3] p. 227. Translated by John Updike as “I believe myself undeserving of Heaven or of Hell,” ref [4] p. 215. For other Borgesian odd views on heaven and hell, or lack thereof, see “El instante” ref. [3] p. 228.

[41] Besides the aforementioned “Juan, I:14,” see “Poema de los dones,” “Los espejos,” “Lucas XXIII,” “Límites,” “Baltasar Gracián,” “Milonga de Manuel Flores,” “James Joyce,” “Rubaiyat,” “A Israel,” “Ni siquiera soy polvo,” “El espejo,” “Góngora.” Ref. [3] p. 111, 117, 146, 187, 189, 288, 301, 311, 313, 488, 623 respectively.

[42] In addition to “Cristo en la cruz,” see “El otro,” “Fragmentos de un evangelio apócrifo,” “Para una versión de I King,” “No eres los otros,” “La moneda de hierro,” “La prueba,” p. 199, 328, 462, 467, 469, 538 respectively.

[43] In Ref. [3] p. 328. Ref [4] p. 293.

[44] Borges translated Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, and wrote a small essay/poem about her life.

[45] For example, Castellani, ref [5] p. 189; ref [6] p. 198, 199; ref [7] p. 187; ref [8] p. 198, 202; ref [9] p. 479.

[46] Note that Castellani passed away in 1981, three years before “Cristo en la cruz” was published.

[47] Castellani, ref. [5] p. 191.

[48] Castellani, ref. [6], p. 196.

[49] Castellani, ref. [5] p. 191.

[50] Barcia ref. [10, 11], Planells ref. [14], Romero, ref. [16], Adur ref. [19], Romera ref. [20].

[51] Barcia ref. [11], p. 5.

[52] Castellani, ref. [8]. P. 205. “Hay que olvidar sus blasfemias, que al fin son pocas y disimuladas.” P.L. Barcia goes one step further and ventures that “there is no desire in Borges to scandalize or blaspheme, but to surprise.” Ref [11] p. 3.

[53] Borges, ref [3] p. 111. Translated by Alastair Reid. Ref. [4] p. 95.

[54] Borges, ref [3] p. 475 (Alejandría, 641 AD).

[55] For example, Borges, ref [3] p. 12.

[56] Borges, ref [3] p. 434.

[57] Unsavory opinions of black people such as: “I am a racist. I would take them at their word and we would see who wins. I would cleanse the United States of blacks, and if nobody stopped me, I would do the same in Brazil. If they do not get rid of blacks, they are going to turn the country into Africa.” (“Yo soy racista. Les tomaría la palabra y veríamos quién gana. Limpiaría los Estados Unidos de negros y si se descuidan me correría hasta el Brasil. Si no acaban con los negros, les van a convertir el país en África”). Ref. [21]. p. 1420. The publication of this book by Bioy Casares was bitterly criticized by Borges’ widow María Kodama.

[58] Among other unfavorable remarks by Borges about the Jews: “I am not an anti-Semite, but that everywhere the most different peoples have persecuted the Jews is an argument against them.” (“Yo no soy antisemita, pero que, en todas partes, los pueblos más diferentes hayan perseguido a los judíos es un argumento en contra de ellos.”). Ref. [21]. p. 139.

[59] In a speech at the National Arts Club of New York in 1993, Solzhenitsyn argued that art shows what is within men’s souls, and that modern art discloses the spiritual desolation in modern souls.

[60] Borges, Credo de Poeta. Conferencia pronunciada en la Universidad de Harvard, curso 1967-1968

[61] Planells, ref [15] p. 176 ss.

[62] Pascal’s wager postulates that people wager with their lives whether God exists or not. Pascal states that men should live as if God existed. If God does not exist, such persons will only regret some deprivations, whereas if God does exist, they will receive eternal gains and avoid eternal damnation.

[63] Barcia ref [11] transcribes the letter written by Father Pierre Jacquet to Monsignor Daniel Keegan of Buenos Aires. Alazraki ref [13] Epilogue: On Borges’ death, two eulogies were delivered at Saint Pierre Cathedral in Geneva: one by a Protestant minister and another by Fr. Jacquet, who disclosed in his oration that he had assisted Borges the night before his death, heard his confession and granted him absolution. Also in Williamson, ref [22] p. 491.

[64] “Actually, I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains some samples or glimpses of final victory.” Carpenter, Humphrey, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, 195: “From a letter to Amy Ronald, 15 December 1956.”